Five years after Brexit, Britain and the European Union are poised to sign a security and defence pact that could lead to the broadest, deepest set of repairs to the EU-UK relationship since the 2016 referendum.

Progress towards a new deal on trade could take months. But barring a last-minute impasse, Keir Starmer, Ursula von der Leyen and their foreign ministers will meet in London tomorrow to forge a new strategic alliance conceived as Europe’s response to Russia’s war machine and the US retreat from global leadership.

The draft pact gives the UK government and British firms a role in joint European defence procurement, on terms to be agreed. It sets out areas for joint action on cybersecurity and maritime security, – including combating Russian threats to sub-undersea cables – as well as protecting other critical infrastructure, freedom of navigation and freedom of overflight. The pact covers “all possible cooperation in terms of security and defence”, Kaja Kallas, the EU foreign policy chief and former prime minister of Estonia, told The Observer. “I think we can always build on that.”

Her words will be welcomed in Downing Street, where hopes that UK strengths in defence would smooth a post-Brexit reset have collided with the reality of 27 EU member states with their own commercial interests.

That has made negotiations “much more complicated”, Kallas said. She warned it was still too soon to be sure the defence pact would be signed, but pointed to agreement on the fundamentals: the summit declaration will state that the biggest threat to European security is from Russia. She said: “Everybody is on board with that.”

Agreement on shared threats may prove the easy part. Starmer is finding his broader reset harder to negotiate in Brussels and to sell at home, despite strong support for closer ties with Europe and a clear need to cut cross-Channel red tape.

A sticking point has been France’s demand that any security deal be tied to a long-term agreement on fisheries, which the UK wants to be time-limited. Whitehall sources say fish and security are not for member states to negotiate and anyway are “100%” unrelated. Others said friction over such issues caused the tone of talks to darken. By the end of the week they were at a “very difficult” stage, according to one diplomatic source. “The mood was not good at all.”

‘Agreement on shared threats may prove the easy part. Starmer is finding his broader reset harder to negotiate in Brussels and to sell at home’

‘Agreement on shared threats may prove the easy part. Starmer is finding his broader reset harder to negotiate in Brussels and to sell at home’

France is not alone in trying to tether one part of negotiations to another. The UK has been angling for a sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) deal to cut customs checks on food and agricultural products, and linked it to progress on the youth mobility scheme sought by the EU. One source said: “We are only going to do youth and fish if we get SPS in return.”

Yet even on youth mobility, Labour has shifted and is now considering a “smart and controlled” scheme, which would mean time limits and a possible cap on numbers coming to the UK. Britain is refusing to budge on the demand for the same university fees for EU students as domestic ones.

Labour is even more focused on what it believes it can sell most easily to voters – jobs, bills and borders. As well as boosting export industries, – including defence – the priority is an SPS deal to bear down on food prices, and a deal to tackle illegal immigration in small boats. If the security pact is agreed, sources suggested it will include new language on how both sides tackle irregular migration.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Starmer hopes to make history tomorrow. It’s a reasonable goal. The UK remains boxed in by its own red lines – no single market, customs union or free movement – and in Brussels the wounds from years of Brexit negotiations are “still fresh”, Kallas said – a startling admission from a natural supporter of closer EU-UK ties. But the trust squandered in those negotiations is being rebuilt. The economic and strategic imperatives driving Britain and Europe closer together are strong.

Nick Thomas-Symonds, the UK’s minister for European relations, has a cordial relationship with his European Commission counterpart, Maroš Šefčovič; the pair are said to swap recommendations for Slovakian red wine and Welsh whisky.

Enrico Letta, the former Italian prime minister, argues in The Observer today for a role for London in a new EU capital markets union, and the practical effect of a security pact could be a de facto single market in defence procurement.

“I certainly wouldn’t use that phrase,” a Whitehall source cautioned – and caution has defined both sides’ approach to this summit. Yet even if it yields only a “cobbled together” communique – as some fear– they will have turned a corner.

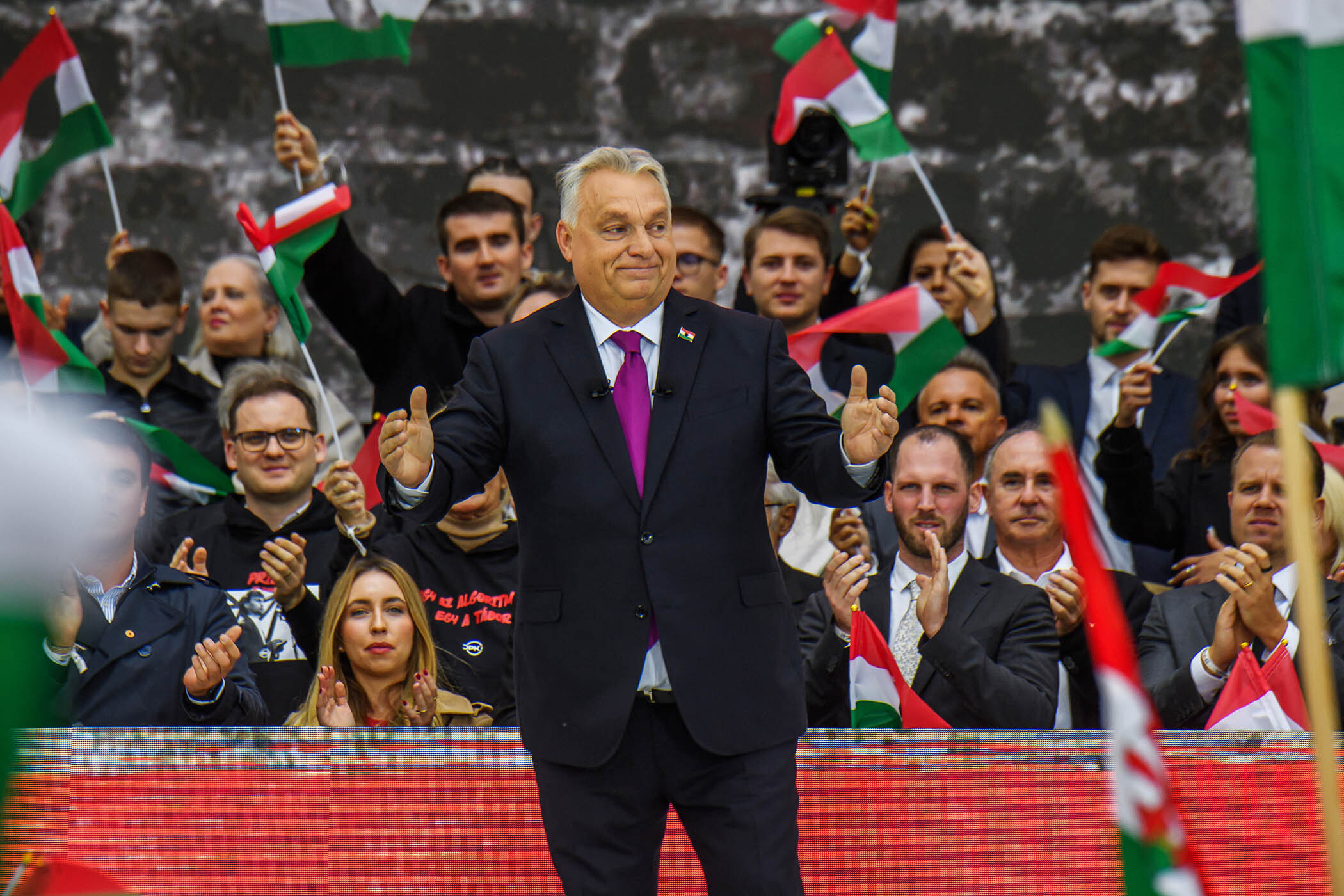

Photos by Leon Neal/Pool via AP