Rachel Reeves has a growing black hole to fill. A combination of the sluggish economy, U-turns on welfare and winter fuel payments, and a never-ending list of problems that need fixing means the chancellor is gearing up for another challenging budget, in which she needs to raise as much as £30bn.

As she ruled ruled out raising income tax, VAT or employee national insurance before the election, her options are limited. These are some of the options being considered by the Treasury:

Gambling tax

An online betting tax could raise £3bn, according to the centre-left thinktank the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR). At the moment, online casinos pay just 21% tax on their profits under the remote gaming duty, putting the UK well behind other countries.

For example, in the Netherlands they pay 40%, in Austria the tax is 54 % and in the US state of Delaware it is set at 57%.

The IPPR proposes that online betting companies should be taxed at 41%, which it says could fund the forthcoming poverty strategy, an idea that has also previously been backed by former PM Gordon Brown.

The Treasury has already launched a consultation on the issue, which suggests there is an appetite to act, and it would be a relatively easy tax to land politically.

Bank tax

Another potential source of income, also endorsed by Brown, is the interest paid on cash held by commercial banks at the Bank of England.

Paul Tucker, the former deputy governor of the Bank, has proposed a tiered reserves system that would involve a lower interest rate being paid on some of the funds held at the central bank. The New Economics Foundation thinktank has calculated that this could raise £3.3bn. Charities working to alleviate poverty could benefit from another £3bn through changes to Gift Aid.

Related articles:

Stealth tax

Reeves could opt for the same approach deployed by her predecessor Jeremy Hunt. In many respects, it is the easiest option: not technically a tax rise, Hunt’s six-year freeze on income tax thresholds is estimated to bring in about £40bn a year with rising inflation. Keir Starmer last week refused to say whether the government would lift this freeze in 2028, despite it being a prior commitment.

Triple lock

Some experts think this approach could offer Reeves some relief from the all-powerful bond markets. Should the government start to signal a change – for example, to ensure that pensions rise in line with earnings, rather than the higher of earnings, inflation or 2.5% – that would create some fiscal headroom. It is not a tax rise, and so by that token should be more palatable, but after being forced into a U-turn on winter fuel payments, it would take a brave chancellor to mess with pensioners again. Not least when Reeves is actively eyeing plans to lower the rate of tax relief on pension contributions.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Wealth tax

Another thing Starmer refused to rule out last week was a wealth tax, which has reignited the debate about a flight of the millionaires. Former Labour leader Neil Kinnock has proposed a 2% levy on assets of more than £10m, which he argues could raise as much as £11bn for the Treasury. A YouGov poll found strong backing for this move, with 49% of people “strongly supporting” it, while 26% “somewhat support” it. However, such an approach has been tried – and reversed – in many other countries. There are several problems with the practicalities not least the concern that it really could push millionaires away.

Other options on the table

One-off levies to pay for specific issues such as defence and social care have been floated, but never realised. A new highest rate of income tax could be theoretically introduced without it breaking the exact wording of the manifesto (although perhaps not the spirit). Reeves has previously pledged not to increase corporation tax above the 25% rate now but this is seen as potentially easier (and more lucrative) than a new wealth tax.

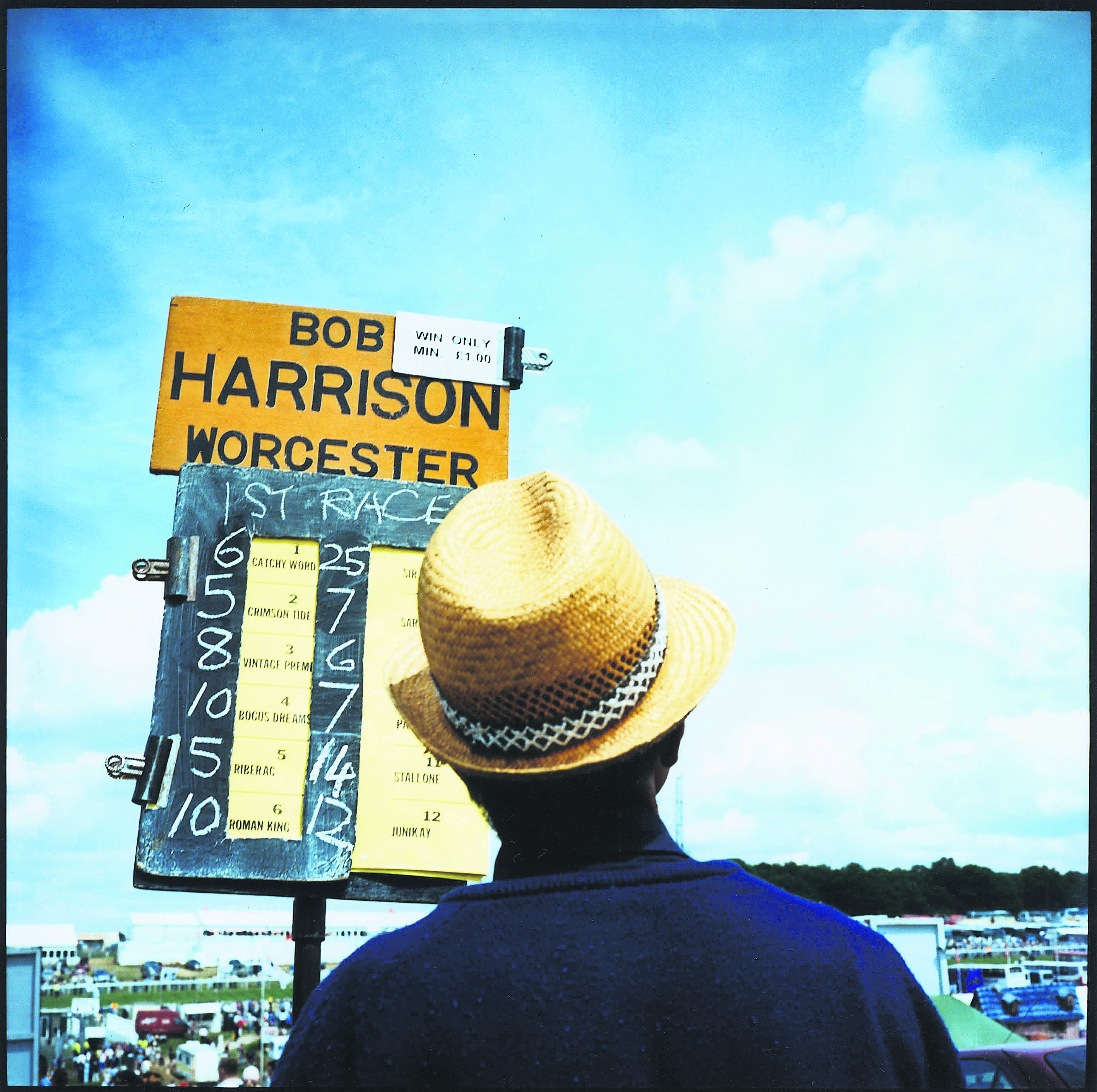

Photograph by Antonio Olmos