Suddenly it’s the hot topic. Will AI take my job, asked C4’s Dispatches last week. As the government dashes to join the new AI revolution, the question casts heavy shadows over those of working age. How long have I got? What can I do instead?

Every now and again I amuse myself wondering how long my husband and I might have to wait for AI to get us up, washed and dressed. Short of acquiring a Blade Runner replicant – and knowing my luck, it would go rogue – there is nothing remotely approaching a sophisticated, interactive care robot. Nor, I suspect, will there be.

Imagine the programming it would need to handle bodies safely. Would it catch me, say, if I started to fall while transferring out of bed? How would it cope when my husband refused to cooperate?

These simple but nuanced skills, the basics of human interaction, are way beyond the reach of today’s AI. The Japanese have been trying to build care robots for decades – they’ve got as far as a machine with pincer arms which grips someone’s torso to stand them up. AI researchers are only just developing haptic sensors, which would replicate some sense of touch, again fundamental.

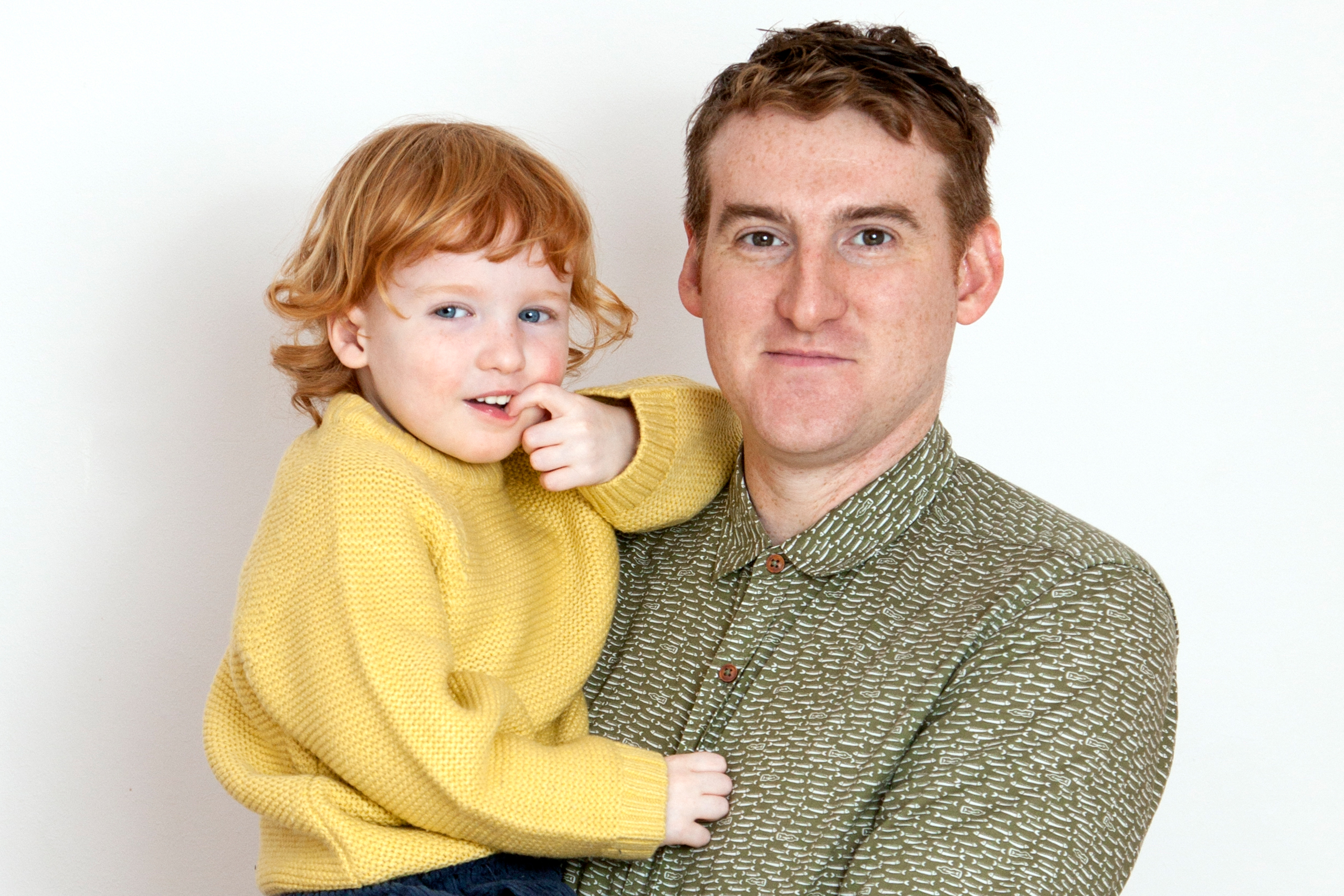

There is a strong argument that all the soft, hands-on skills employed in social care, nursing and raising small children – basically looking after human beings at times of vulnerability – may turn out to be resistant to AI. (It’s a separate debate about whether they should, ethically, always remain so, certainly in the case of small children.)

It’s interesting, this. It cuts to the heart of the whole nerdfest of technology. These soft skills are of course predominantly and traditionally women’s skills – the physical and manual acts of caring. And it is predominantly men who are making the most outrageous claims about how AI will do everything, completely disregarding the vast swathe of work which is arguably the most important. Funny that.

But genius tech bros are rarely responsible for raising children or caring for the elderly – the essence, perhaps, of being human. Dr Roman Yampolskiy, whose preoccupation is controlling AI, scaremongered earlier this year that the development of humanoid robotics would automate all physical labour by 2030, leaving 99% of workers unemployed.

Confidence in AI is highest in communication, consulting and research – and low in health, social care, social work and education

Confidence in AI is highest in communication, consulting and research – and low in health, social care, social work and education

The existence of softer skills has obviously escaped Dr Yampolskiy, whose main areas of interest include behavioural biometrics, digital forensics and genetic algorithms. For his part Mustafa Suleyman, co-founder of DeepMind, has noted that robotics will act as “AI’s physical manifestation” and utterly transform society.

Related articles:

Really? Women wouldn’t say anything as daft. The Tony Blair Institute has researched how attitudes towards AI vary across professional and demographic groups. Confidence is highest in communication, consulting and research – and low in health, social care, social work and education. Women are also notably more unconvinced than men. (They’re realists.)

In fact the two sectors most sceptical about AI are social care and construction – the same sectors most desperate for staff. They’re both intrinsically messy, chaotic, scattered industries. They bodge along. And the pragmatists who populate them know fine that AI can’t rescue them. The only on-site construction AI on the horizon is a robot brick-laying system.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Dispatches came to the fascinating conclusion that we could end up with humans doing all the drudgery and AI taking all the high-end jobs. Building houses and looking after people are vital jobs in need of a rebrand; perhaps this is a golden opportunity. Yee-ha. All my carers are over 60; I welcome the prospect – just pass me that towel, please – of some young replacements from KPMG.

Melanie Reid is tetraplegic after breaking her neck and back in a riding accident in April 2010

Photograph by Adek Berry/Getty Images