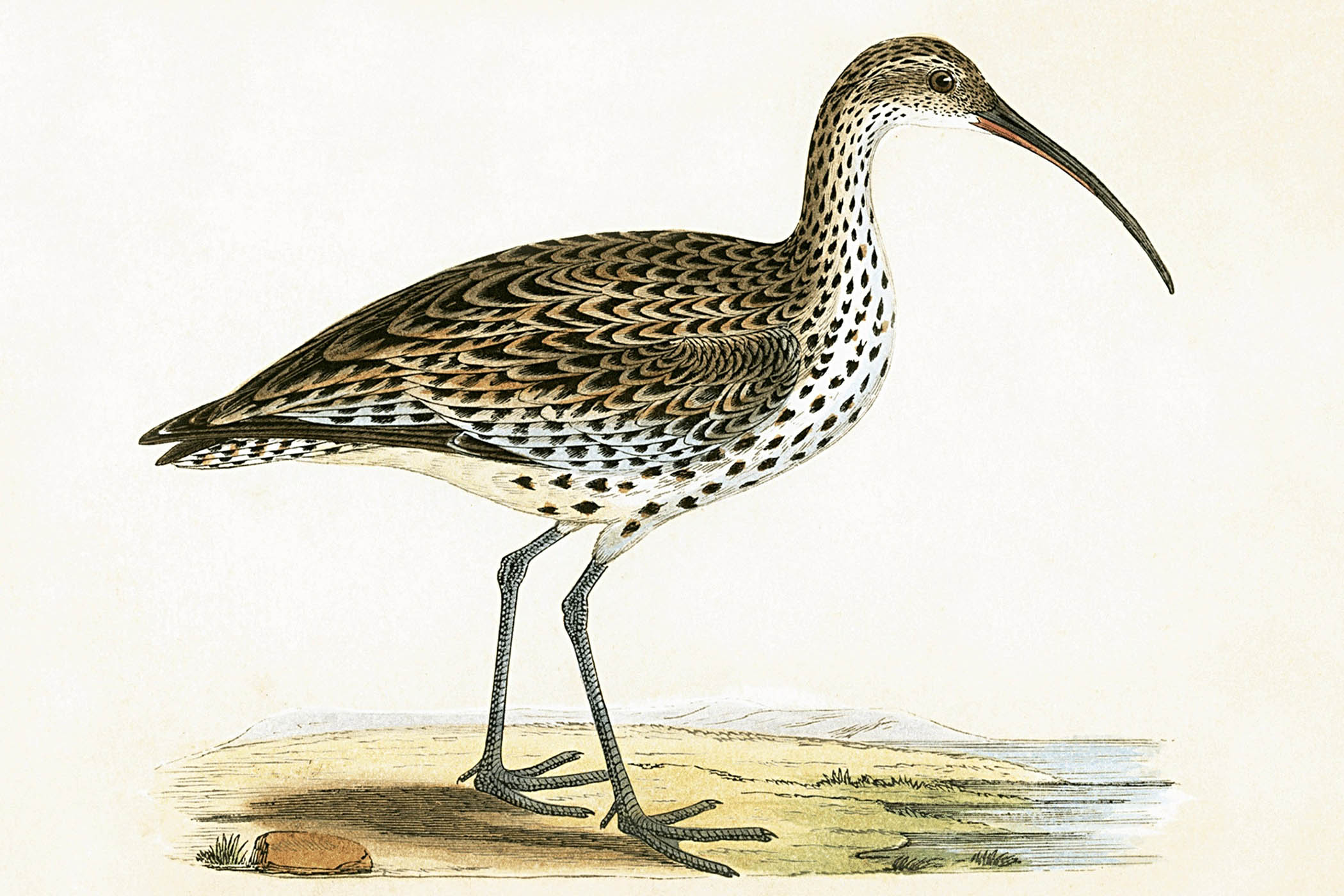

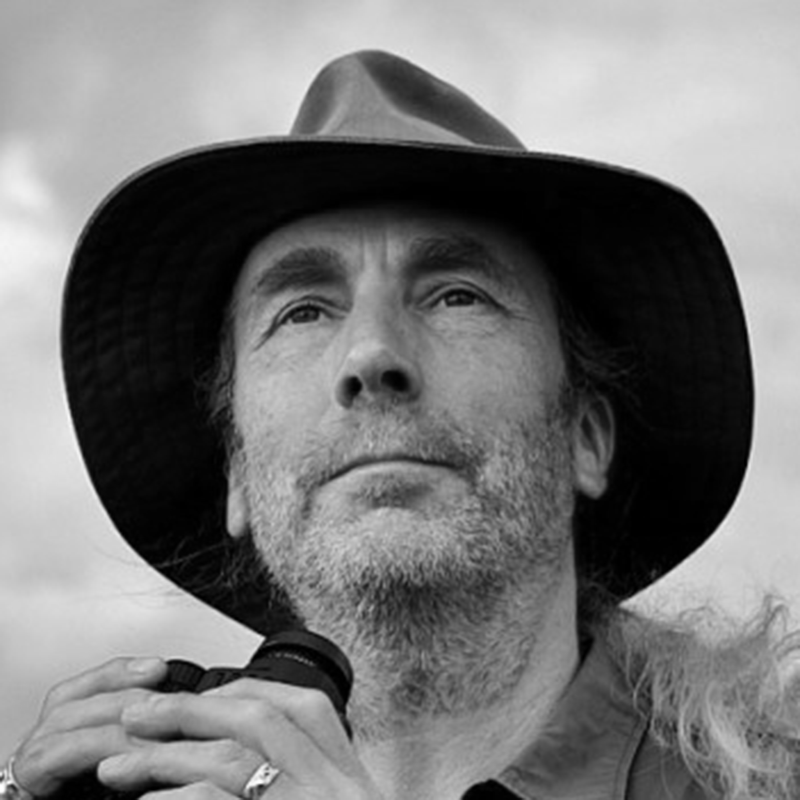

At the annual Global BirdFair – held this year in Rutland – you always bump into old friends, and besides, I had a book to publicise. And there was the conservationist Martin Davies – and I was very damn glad to see him. So we had a beer and talked about birds and birders we had known, and it was all very satisfactory. And then the bombshell. “You’ll remember the slender-billed curlew?”

“Of course,” I said. We’d made an expedition to Morocco in search of that extraordinary and elusive beast.

“It’s extinct. According to a scientific paper last November.” This was truly shocking. “We must have been among the last people ever to see one.”

Perhaps the person who saw the last dodo felt the same way: like looking over a cliff edge and leaning out a little bit too far for comfort.

Martin later found his notes from our trip, so I can say with absolute certainty that at six in the morning we met our guide Hassan Dalil, who took us to Merja Zerga lagoon, and there, feeding daintily among pastel-coloured wild cresses, was our slender-bill.

It was, most considerately, with a small group of Eurasian curlews, the species we find in Britain. Considerate because it was quite obviously different – like a dancer hanging out with bodybuilders. Martin, a top-quality observer, noted: “Slim black bill, very significantly shorter than bill of Eurasian curlew. Lesser coverts dark brown, showing as small dark patch on side of body in closed wing...”.

The date was 15 February 1995. On 25 February, Chris Gomersall photographed the same bird. And that is the last record of the slender-billed curlew. Last and final station-stop, as they say on the trains. No one will ever see one again.

In November last year, a group of ornithologists from organisations including the RSPB, BirdLife International and the Natural History Museum agreed that the bird was almost certainly extinct. It’s expected that the International Union for Conservation of Nature will make this official in October: the first mainland European bird to go extinct in recorded history. (The great auk and the Canary Islands oystercatcher were island species.)

The bird had an unusual east-west migration; winter on swampy land all around the Mediterranean, spring and summer in Siberia. The last person to see a slender-billed curlew nesting was Valentin Ushakov in 1924: “With a feeling of deep satisfaction, I watched the magical picture and felt very happy having discovered a new page in the great book of nature,” he wrote.

John O’Sullivan was part of an expedition to the Kazakh steppe in 1990. “The last nest was found in forested steppe,” he said. “We looked there, but couldn’t find anything.” They set out from Novosibirsk in Siberia with almost 39,000 sq miles (100,000 sq km) to search and it turned out to be a wild slender-billed curlew chase.

What went wrong? No one can say for sure, but the bird was caught in a pincer movement: extensive habitat destruction and relentless persecution on migration. The process of reclaiming farmland from the steppe began in the 19th century and accelerated in the 1950s under Nikita Khrushchev’s Virgin Lands campaign.

The last photograph of the slender-bill, taken in Merja Zerga, Morocco. Photograph by Chris Gomersall

The birds were shot on migration and sold in markets in Italy and elsewhere. Now they are gone. Posing the question: does it actually matter? Does it matter to anyone at all apart from a couple of old birders?

The extinction of the slender-billed curlew is not a one-off. It’s part of an emerging pattern. There is an extinction crisis as well as a climate crisis, and if it’s permitted to continue, it will be even more devastating.

Extinction isn’t like taking a piece from a jigsaw puzzle. It’s like taking a brick from a castle. The extraction affects nearby bricks and weakens the entire structure. Every ecosystem is incomprehensibly complicated, involving uncountable numbers of species: remove one and you change everything.

So you can’t say: “We’ve lost a curlew; well, there are eight other curlew species – what are you complaining about?” (And, anyway, there’s probably only seven; the Eskimo curlew is likely to be declared extinct next year.)

A species is a breeding community: the largest group of organisms that can mate and produce viable young. In other words, every species we lose is gone for good and the part it played in the global ecosystem is no longer performed. An extinction ultimately affects every other species on the planet. Including our own.

There have been five mass extinction events in the history of life on Earth. The most recent was 66 million years ago and it did for the (non-avian) dinosaurs. Almost every species weighing more than 25kg (55lb) became extinct. We are now in the midst of the sixth extinction. Humans have changed the planet so much that we’ve pushed it into a new geological age: the Anthropocene. Its keynote is extinction.

The destiny of all species is to become extinct, Homo sapiens and all; 98% of all organisms that ever lived are extinct. But the normal or background rate of extinction is reckoned to be between 0.1 and 1 species lost in every 10,000 species over the course of 100 years. The current rate is between 100 and 1,000 times higher.

My book Planet Zoo (not my title) was published in 2000. The subtitle was: 100 Animals We Can’t Afford to Lose. One of those has already gone. This is the baiji or Yangtze River dolphin; lost to the overcrowding, pollution and overuse of the great river system it lived in. The dolphin, which could be almost 9ft long, was last seen in 2002. Megafauna extinctions are more vivid than those of beetles and worms, so let’s consider the thylacine or Tasmanian tiger, gone in 1936, while the Japanese sea lion, the Caribbean monk seal and the bubal hartebeest were all gone in the 1950s. The northern white rhino – a mere subspecies but still a considerable loss – is reduced to two ageing females, so functionally extinct.

What’s next? Take your pick: vaquita porpoise, red wolf, Sunda pangolin, Ganges shark, saola bovid ...

Birdwatching can be understood as a study and a celebration of biodiversity. Birds show us what’s happening with everything else. In this country there are 73 million fewer birds than there were 50 years ago, according to recent data.

I have covered the Wimbledon tennis tournament on and off since the 1980s, and always saw plenty of swifts flying over the Centre Court. This year, covering the event for this newspaper, I didn’t see one. We have lost more than two thirds of our swifts in 30 years. Gone because we are too many.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The human population stands currently at 8.2 billion, projected to rise to 10.3 billion by the 2080s. The world population of cattle is 1.5 billion, of sheep 1.3 billion, of pigs 780 million. In 2021, the land given over to wheat production totalled 220.7 million hectares (almost 545 million acres), for rice 150 million hectares.

Not much room left for curlews. Or the invertebrates they feed on. Or any non-domestic animal that hasn’t acquired the skill of living off human wastefulness. The brown rat is doing fine. Cockroaches, very nicely, thank you.

But does it matter? Well, let’s forget the moral question; after all, most people in power do. And let’s leave aside issues of mental health, urban angst, quality of life, NHS tranquilliser bills etc. Does the loss of curlews, seals, dolphins and uncountable invertebrates materially affect humanity?

Obvious example: pollination. Every third mouthful of food we eat depends on pollinators. In the Central Valley in California there are no wild pollinators left to serve the vast monoculture of almonds; they have to bus in bees – there are more than 400,000 hectares of almonds.

Now let’s go back to biodiversity. There are at least 10,000 bird species on the planet. A million insect species have been named and described; there may be 10 times that number still to be discovered.

That’s the way nature has always worked: by making lots and lots of different species. Diversity is nothing less than the way life works. But humanity has chosen monoculture.

It will be interesting for future scientists (if there are any) to analyse the sustainability of monoculture. Perhaps it will work, even if the life it supports won’t be much fun. Or perhaps it will verify the rivet-popper hypotheses. A big passenger aeroplane has lots of rivets. It can pop one: no problem. Keep on flying. And another. And another. And another ... but there will come a point when the aeroplane falls apart in the air.

One species, one rivet. One planet, one experiment.

We can give up, of course. But there is another option. I spoke to Nicola Crockford, principal policy officer at the RSPB. “The slender-billed curlew is the greatest tragedy of my life,” she said. “I use the example of the slender-billed curlew all the time; when I talk about migration flyways, I always start with the story of the slender-billed curlew. We can use the knowledge and the experience gained from the slender-billed curlew to stop it happening again.”

The spoon-billed sandpiper is still with us – just about – and preventing its extinction is an attainable goal. Its future depends on cooperation between nations, for – like the slender-bill – it’s a bird that crosses continents. Cooperation takes place under the Convention on Migratory Species, with more than 130 member states.

In October in Bonn, where the convention was signed in 1979, there will be a memorial service for the slender-billed curlew; for the species as a whole and for the last slender-bill of them all – perhaps the one Martin and I saw at Merja Zerga.

Mourning, yes. But not just. “It’s a call to arms,” Crockford said. “We must use the loss again and again so that the slender-billed curlew didn’t die in vain.”

Illustration by Private Collection/Bridgeman Images, Chris Gomersall