As he stepped on to the infield of Oxford University’s Iffley Road track, allowing Sir Roger Bannister to continue on his way to the world’s first sub-four-minute mile (3:59.4), Chris Brasher’s place in history was assured. Brasher, one of the pacemakers alongside Chris Chataway, would be one of the men who helped make the impossible possible. Little could he have known just how far his own personal legacy would extend.

When Brasher, who won the Olympic 3,000m steeplechase gold in 1956, launched the London Marathon in 1981 – with fellow former athlete John Disley – any thought of creating an event of world-record proportions would have seemed fanciful. Yet, all being well, today’s 45th edition of his brainchild will break New York’s record of 55,646 finishers, officially making it the largest marathon on the planet.

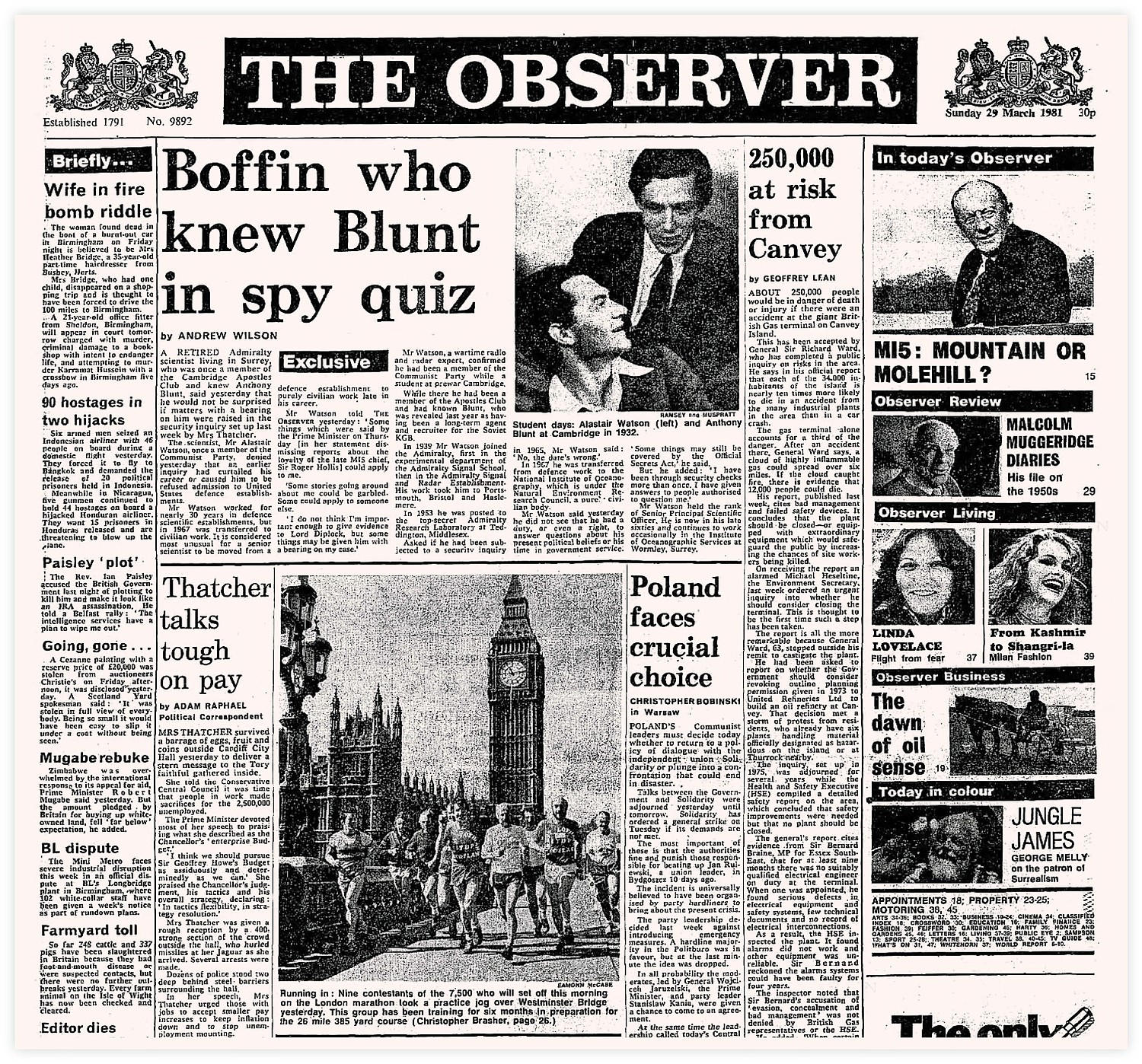

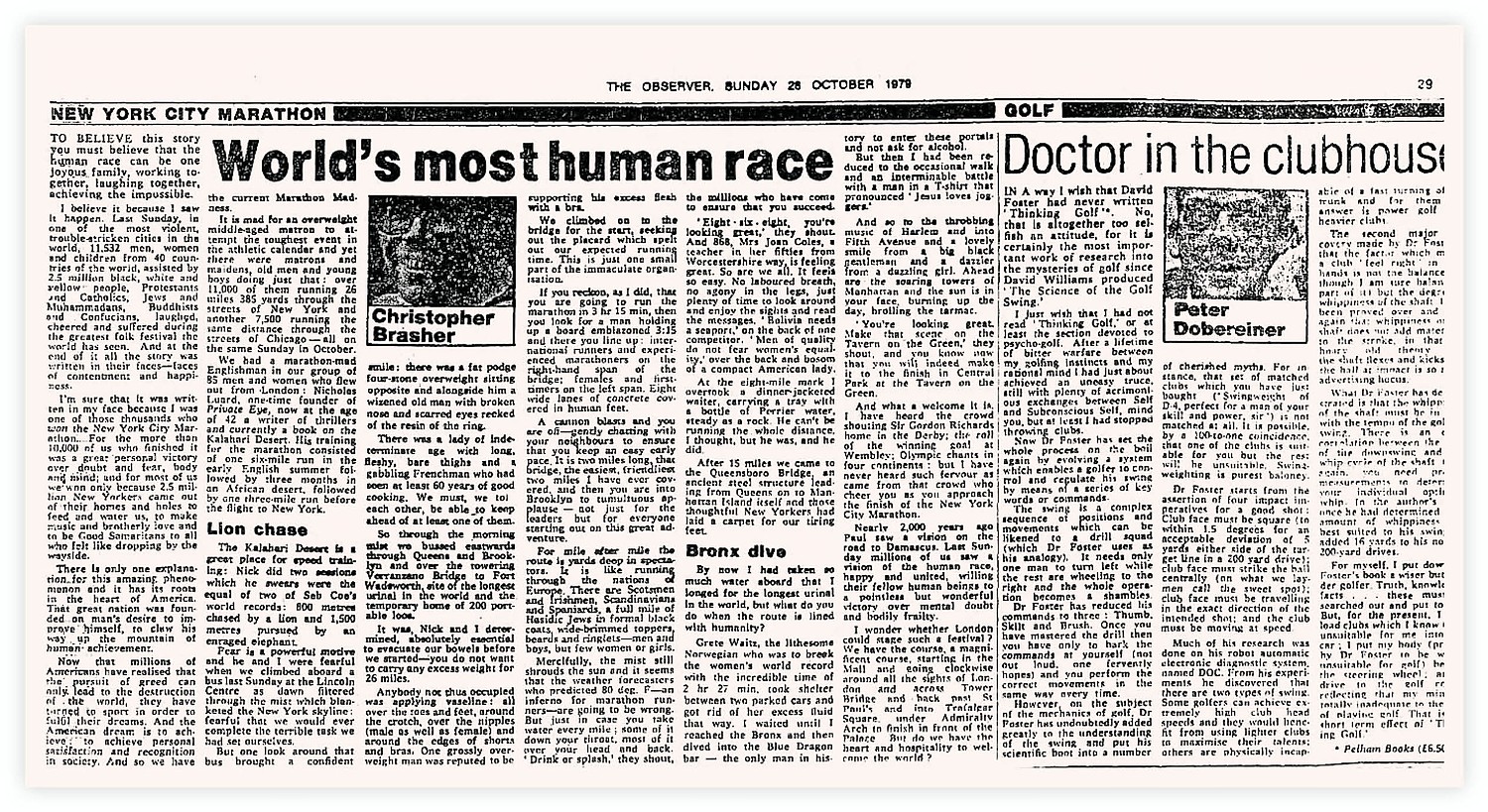

Fittingly, it was the unexpected wonderment of a trip to the Big Apple in 1979 that planted the seed from which an extraordinary history has sprung. By that stage, Brasher had reinvented himself an acclaimed businessman and respected journalist for The Observer when, somewhat inebriated, he was persuaded to take on the challenge of running the New York Marathon. He returned inspired.

“To believe this story, you must believe that the human race can be one joyous family, working together, laughing together, achieving the impossible,” he wrote in The Observer on 28 October 1979. “Last Sunday, in one of the most trouble-stricken cities in the world, 11,532 men and women from 40 countries, assisted by 2.5 million [spectators]… laughed, cheered and suffered during the greatest folk festival the world has seen.”

He concluded by musing: “I wonder whether London could stage such a festival? We have the course, a magnificent course… but do we have the heart and hospitality to welcome the world?”

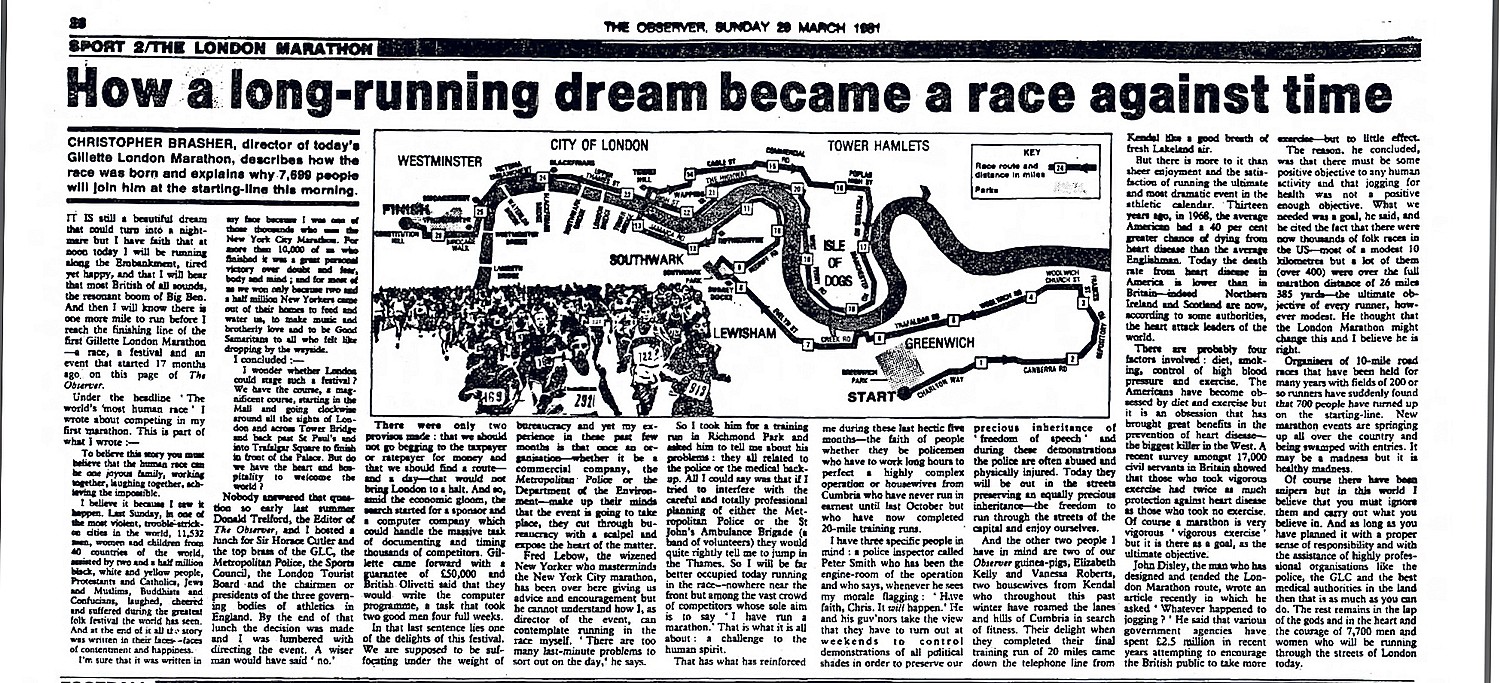

Two years later, he emphatically answered his own question when, in conjunction with his great friend Disley, the 1952 Olympic 3,000m steeplechase bronze medallist, he staged the first London Marathon on a course that has remained broadly faithful ever since: taking in Greenwich, Cutty Sark, Tower Bridge, Embankment, Big Ben and Buckingham Palace.

In fact, it was not the first event of its kind to be staged in the capital. Largely continuously, from 1909, the Polytechnic Marathon had taken different routes over often indiscriminate lengths around predominantly west London and Windsor. But this was a previous era of marathon running; one marked by diehard participants only, uninspiring courses and an overwhelming lack of on-course support. Brasher and Disley wanted to change that.

Informed by the otherwise supportive authorities that no public money would fund the dream, Brasher intended to mortgage the family house to stage the inaugural event. “But my mother refused to let him do it,” Brasher’s son Hugh, now London Marathon Events chief executive, recalled. Fortunately, the American shaving company Gillette provided £50,000 and the event went ahead on 29 March 1981, providing as it did the iconic image of the winners, Dick Beardsley and Inge Simonsen, hand in hand crossing the finish line in unison.

There have been moments of strife. In the 1980s and 90s, the threat of IRA attacks hung perpetually over the city, while the 2013 Boston Marathon terrorist bomb that killed three people occurred in the week of London’s event, prompting a last-minute wholesale security review.

More recently, the Covid pandemic forced the cancellation of the mass event in 2020, with the elite races delayed six months and shifted to the biosecure environment of St James’s Park, each athlete wearing a device to ensure they remained suitably socially distanced. Around the world, 43,000 ran the event virtually.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Much of the London Marathon’s success lay with the maverick figure of former 10,000m world record holder David Bedford, a wonderful relic of a time when public figures could happily raise hell on and off the sporting stage with little chastisement. A night in a German jail cell after a bar incident – while British team captain at the World Cross Country Championships – only further enamoured the public to his eccentricity. “The trouble with sport now is that there aren’t any great characters left,” he told a journalist in 2011. “It is all too serious, too intense. No one enjoys themselves any more.”

Bedford only took part in the first London Marathon after accepting a bet in the early hours of that morning when deep into a heavy drinking session in the Luton nightclub he owned. Soon enough, he was part of the event’s furniture, serving as race director for a dozen years and compiling the elite fields for almost three decades until 2018.

His tenure saw multiple world records broken, including two by Britain’s Paula Radcliffe, who clocked two hours, 15 minutes and 25 seconds in a mixed race in 2003, before infamously overcoming mid-race bowel issues to add the women-only world record of 2:17:42 two years later. Kenya’s Eliud Kipchoge, widely considered the greatest male marathon runner, is back today bidding for an unprecedented fifth men’s race win.

Such performances have generated countless sporting headlines, but it is the mass event that commands public attention. Thanks to the unglamorous intricacies of crowd science, more and more people are able to experience it.

From 6,255 finishers at the first edition in 1981, the event has routinely hit landmarks for ever-increasing numbers of people completing the gruelling 26.2 miles: 20,000 in 1988, 30,000 in 1999, 40,000 in 2018 and 50,000 last spring. The expectation is for the latest edition to break new ground globally.

Much of that is thanks to Marcel Altenburg, a former German army captain, who made an unusual career pivot to become one of the world’s leading crowd science experts. His skill is to ensure that quantity does not eclipse quality.

“The work that he’s done to help us model the marathon and how we release the runners has made a massive difference,” Hugh said. “The marathon was less crowded in 2024, with nearly 54,000 finishers, than it was in 2019 with 40,000.

“For example, we now release runners over a two-hour period whereas they used to be released over a 42-minute period. There is a lot of science and algorithms because this is a massive logistical operation, not only in moving people, but giving them water, giving them gels, transporting baggage from start to finish, and moving spectators. The average runner brings 5.4 people to watch them, and the average person goes to 2.2 locations on the route. We have all of this information and Marcel makes sense of it.”

A remarkable 840,318 people applied through the public ballot for this year’s edition, with more than £1.3 billion raised for charity since 1981. Five ‘Ever Presents’, people who have run each London Marathon, are back today for their 45th consecutive effort.

Surely, it has grown beyond anything Chris Brasher (who died in 2003) and Disley (who died in 2016) could ever have envisaged?

“One of my father’s favourite phrases was from [poet] Robert Browning: ‘A man’s reach should exceed his grasp, or what’s a heaven for?’” Hugh said. “That was part of his DNA, which is part of my DNA.

“I think they would be enormously proud and delighted. It is a unique experience. Where else would you, as an everyday person, get cheered on like Andy Murray on Centre Court or Harry Kane at Wembley? Where else in life would you be riding on a wave of positivity where tens of thousands of strangers genuinely want you to be successful? That feeling is not something you get in any other sport.”

Photograph UPI/Bettmann via Getty Images