Usually when a famous football manager goes up to accept an honorary doctorate, the speech is all sweetness and light.

Reflected glory paints grins on the gowned academics clapping the star at the lectern. The mortar-boarded gaffer dispenses advice to the students about sticking together, training hard and perhaps not getting overloaded in midfield. It tends to be light-touch and ceremonial.

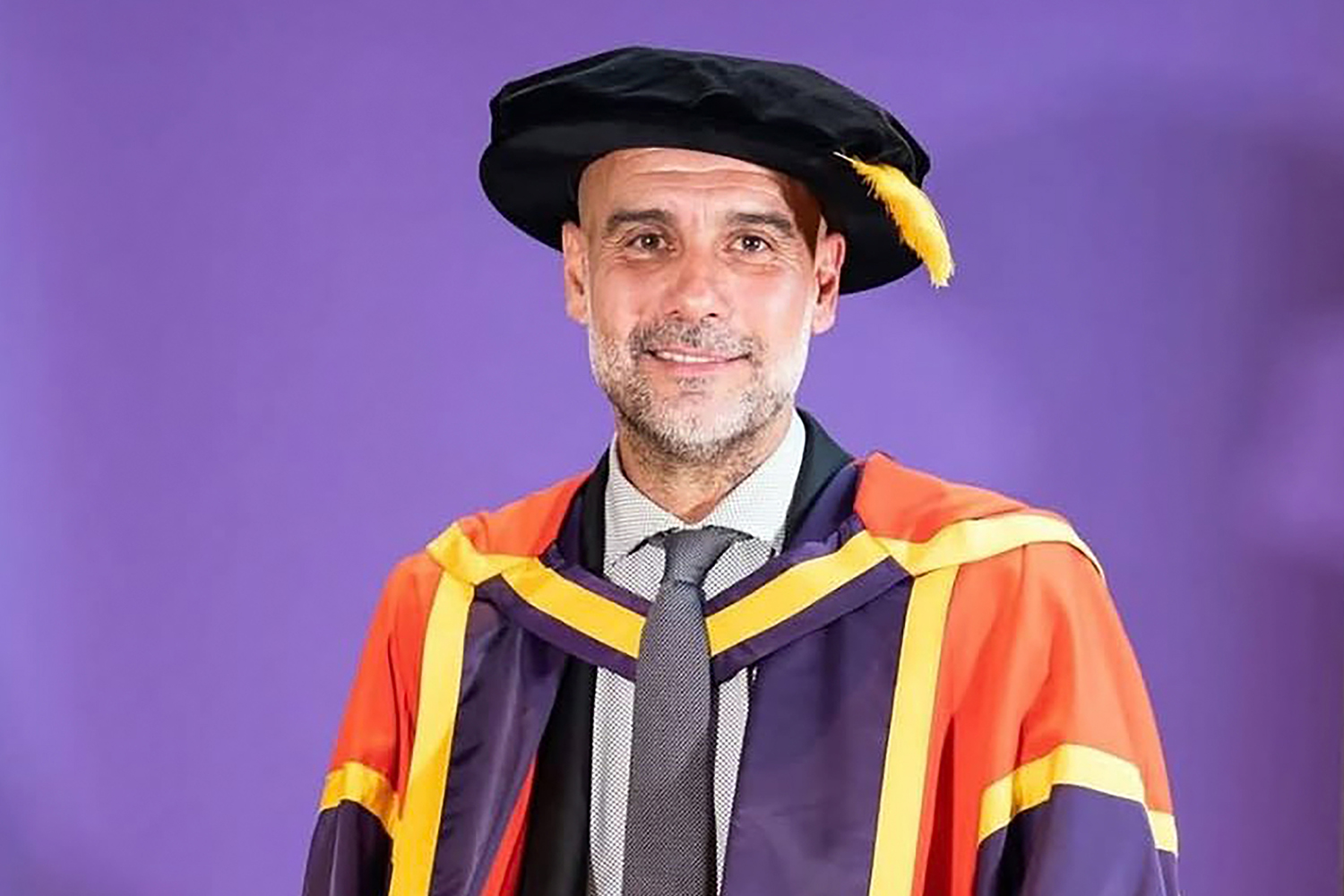

Pep Guardiola chose a different way this week to address Manchester University. If sport leans heavily on the great Seamus Heaney’s poem, “Whatever you say, say nothing”, Guardiola made a deft and heartfelt intervention on the catastrophe that Gaza has become. He was speaking before war between Israel and Iran began breaking out: another conflagration that will challenge sport’s claim of immunity from world events.

‘It’s not about whether I’m right or you’re wrong. It’s about love of life, about the care of your neighbour’

‘It’s not about whether I’m right or you’re wrong. It’s about love of life, about the care of your neighbour’

“It’s so painful what we see in Gaza. It hurts my whole body,” said Guardiola from his script in Manchester’s Whitworth Hall. “Let me be clear, it’s not about ideology. It’s not about whether I’m right, or you’re wrong. It’s just about the love of life, about the care of your neighbour.”

That inarguable appeal to basic human values cut through the world’s most intractable conflict to a way of seeing death that was simply personal and empathetic.

He went on: “Maybe we think that we see the boys and girls of four years old being killed by the bomb or being killed at the hospital because it’s not a hospital any more – it’s not our business.

“We can think about that. It’s not our business. But be careful. The next one will be ours. The next four or five-year-old kids will be ours. Sorry, but I see my kids, Maria, Marius and Valentina. When I see every morning since the nightmare started, the infants in Gaza, and I’m so scared.”

In most spheres, to argue that two things can be true at once is a standard liberal reflex. Thus, the Hamas massacre of Israelis on 7 October was an abomination. Thus, shooting Palestinian children at aid stations is indefensible.

But on the Israel-Gaza conflict, many moderate people have been unwilling to say even both those things together. They fear the opinion-blitzing armies of whataboutery. Saying nothing is easier, especially if the day job exposes them to the reaction of tens of thousands in stadiums and millions online, as it does for Guardiola. The safer path on all sides is one of private, silent anguish.

There is no higher profile manager than Guardiola, who fits Muhammad Ali’s line about looking out of a plane window anywhere in the world, sure in the knowledge that people in the village below would know him. And so, no football coach could have a greater incentive to keep quiet about events in the Middle East.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

In previous forays he has been fined by the FA for wearing a yellow ribbon in support of imprisoned pro-independence Catalans, and joined marchers calling for his native Catalonia to be released from the Spanish state. In his university speech he shared the fable of the “little bird” who unloads droplets of water on to a forest fire because he “refused to do nothing”.

Intermittently, protest in sport has been hot since Tommie Smith and John Carlos gave black power salutes on the podium at the 1968 Mexico Olympics: by today’s standards a mild gesture, but, in the context of America’s civil rights struggle and the Vietnam war, a challenge to American injustice and hypocrisy.

Others will trace the origins to the Suffragettes and Emily Davison losing her life after running on to the track at Epsom in the 1913 Derby and colliding with the King’s horse. The biggest modern convulsion has been around Colin Kaepernick popularising the taking of the knee in response originally to police brutality in America.

In football now, women fight for their rights and the Shrewsbury Town player David Wheeler leads a group campaigning to stop Fifa getting into bed with fossil fuel producers.

Confronting every protest is the delusion that sportsmen and women shouldn’t “stray” into politics. If so, how did we end up with football World Cups in Russia, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, or the Olympics in Beijing, or government doping programmes in Eastern Europe, or any of the countless manifestations of state power?

Guardiola’s critics will say he has been less quick to question the repressive nature of Abu Dhabi, which owns Manchester City. But moral equivalency does a poor job of connecting these two stories when whole families are being wiped out in Gaza and Israeli hostages are still being held.

Guardiola lit the path Gary Lineker was on until Lineker extended his argument from humanitarian concern to Zionism and historic struggles over land – and so gave the BBC a red line to say he had just crossed.

Guardiola could have talked about how you bounce back from a 3-0 defeat, what it was like managing Lionel Messi or how it felt to win the treble at Manchester City. There would have been nothing wrong with any of that. Instead he inverted Seamus Heaney’s line to: “Whatever you say, say something.”