Cheats never prosper. So we are told – and one of the great milestones of maturity is the realisation that they very often do. Donald Trump routinely cheats at golf: they call him Pelé because he kicks the ball with such aplomb.

There’s a new Sky documentary about the extraordinary life of Damon Hill, who achieved a kind of redemption by becoming Formula One drivers’ champion 28 years after his father Graham won it for the second time. He would have won it two years earlier, in 1994, had it not been for one of the most spectacular unpunished cheats in history.

Sport is a pretend world. It is governed by rules peculiar to each sport and played according to customs tacitly if imprecisely agreed on by the participants. This precarious tightrope-walk is the essence of sport. And there are always those who think it’s better to win by kicking the ball on to the fairway than to be beaten by a better player. It all depends on what kind of Pelé you are and how you define a beautiful game.

Michael Schumacher - I collide therefore I am

Michael Schumacher was leading the championship from Hill by a point when the final race started in Australia. He crashed, but as Hill passed him, he drove into Hill’s car, forcing him to retire as well. It was judged a racing incident and Schumacher won the title. Three years later Schumacher made a similar move on Jacques Villeneuve. This time he was retrospectively disqualified for the entire season.

Toni Schumacher – See above

The unrelated Toni Schumacher was in goal for West Germany in the 1982 World Cup semi-finals. Patrick Battiston ran on to a perfect through-ball from Michel Platini: and Schumacher, ignoring the ball, ran – leapt rather – into Battiston. Battiston was knocked unconscious, lost two teeth, suffered three cracked ribs and damaged vertebrae. The referee awarded a goal-kick; West Germany won on penalties.

Colin Cowdrey & Peter May – Who needs a bat?

So what is cheating? Is it different from clever exploitation of the rules? In 1957, Colin Cowdrey and Peter May played Sonny Ramadhin, great West Indian spinner and former scourge of England, by kicking the ball, bats well out of the way. They put on 411 together while Ramadhan bowled 98 overs, all in his cap. He appealed and appealed for lbw, but the umpires gave the traditional benefit of the doubt to the batter every time.

Armin Hary – The thief of starts

Armin Hary won the 100 metres at the 1960 Olympics Games for Germany. He was known as “the thief of starts”. His reaction time was calculated at 0.04 seconds. These days anyone who starts before 0.10 seconds is disqualified for a false start. Perhaps Hary was exceptionally gifted. And perhaps that gift was for anticipation.

Tonya Harding – If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em

Tonya Harding won the 1994 US skating championships. It was a great victory, achieved at least in part because her rival Nancy Kerrigan was injured – and the injury was the result of an assault by people hired by Harding’s ex-husband. Harding was later convicted of involvement after a complex bout of plea-bargaining and stripped of her title.

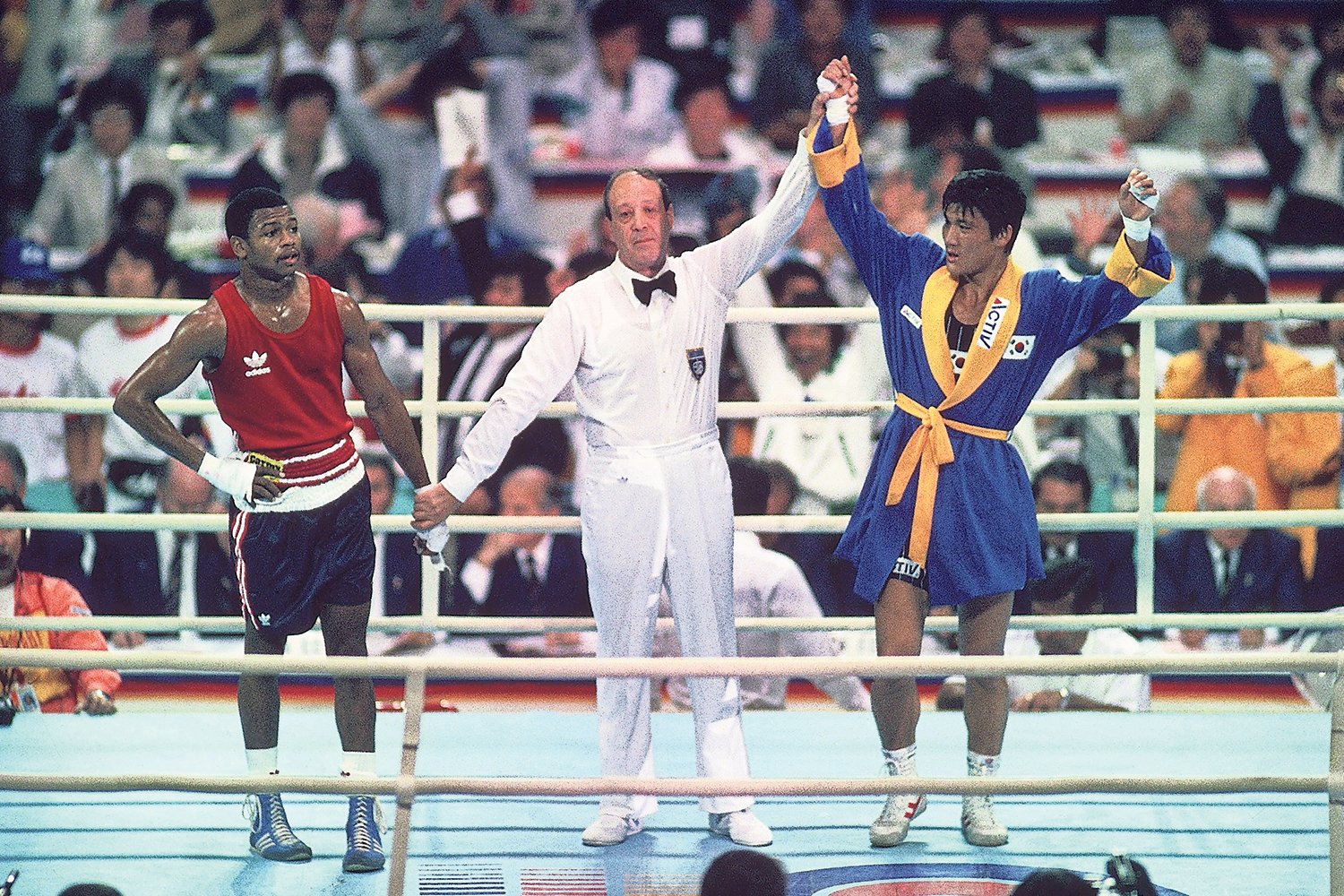

Park Si-hun – A man more punched against than punching

In the Olympic light-middleweight boxing final of 1988 in Seoul, the Korean boxer Park Si-hun landed 32 punches on the American Roy Jones Junior and received 86. The judges awarded the fight to Park by a 3-2 margin. Two of the judges were later banned and the scoring system was changed. Jones was later world champion at four different weights; Park became a schoolteacher.

Florence Griffith Joyner – At least we still have her records

Florence Griffith Joyner won three sprint gold medals at the 1988 Olympic Games. Her records for the 100 metres and 200m still stand. She retired the minute out-of-competition drug-testing was introduced. She died at 38 from an epileptic seizure. She never failed a drugs test and drugs played no part in her death, yet there is little doubt that her extraordinary achievements were powered by drugs.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Diego Maradona – Un poco con la cabeza di Maradona y otro poco con la mano de Dios

The World Cup of 1986 was held in Mexico; England were playing Argentina in the quarter-finals. The score was 0-0 when Diego Maradona ran through on to a rising ball. The England goalkeeper Peter Shilton, eight inches taller, was favourite but Maradona beat him and scored. With his hand. It became known as the Hand of God goal. Argentina won the match and later the tournament.

East German swimmers – Pity the poor cheats

In 1976 the East German women won 11 of the available 13 gold medals for swimming at the Olympic Games in Montreal. The state doping programme that made this possible was later revealed in Stasi files after the fall of the Soviet empire. Cheats are supposed to be bad people: here we have to consider the victors as victims.

Bodyline – A batter has something more valuable than his wicket

England had a cunning plan to confound the nonpareil Don Bradman in cricket’s Ashes series between England and Australia of 1932-33. Dubbed Bodyline, it involved bowling at the body –no helmets back then – with a cluster of fielders behind the batter’s back catching any ball he fended off. England won the series, Australia still maintain it wasn’t cricket. The tactic was later outlawed. Cheating? Or just the longest whinge in sporting history?

Mostafa Asal – When you’ve got them by the balls, their minds and their hearts will follow

Mostafa Asal is world squash champion. A recent YouTube video has made headlines with its analysis of Asal’s technique: tripping, blocking and hitting opponents with his racquet. He once gave an opponent concussion and a perforated eardrum by hitting him with the ball. On another occasion he elbowed an opponent in the crotch. In the British Open last year his opponent Ali Farag suddenly stopped playing on match ball. Replays suggested that Asal had grabbed his opponent by the balls... but it was his title and his prize-money.

Photograph by Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

This article was amended on 7 July 2025. An earlier version stated that the 1986 World Cup was held in Argentina. It was in fact held in Mexico.