Welcome to the Sensemaker, our daily newsletter. It features calm and clear analysis on the stories driving the news across tech, politics, finance, culture and more. The Sensemaker will appear here every morning, but to receive it in your email inbox, sign up on our newsletters page.

The funeral of Pope Francis will be held tomorrow in Rome. After that, attention will turn to electing the next leader of the world’s 1.4 billion Catholics.

So what? This is democracy in its most refined form. By some accounts, the very word “vote” is derived from the vow each cardinal takes ahead of making their pick in front of Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment.

It may also be a bunfight. Pope Francis’s 12 years as pontiff were dogged by a struggle between modernists and traditionalists. Critics railed against his decrees

•

restricting the use of Latin Mass;

•

allowing blessings for gay couples; and

•

permitting divorced Catholics who have remarried to receive communion.

In 2019, a group of conservative clerics signed a letter accusing Francis of creating “one of the worst crises in the history of the Catholic Church”. These divisions are likely to come to the fore as cardinals jockey to replace him.

How to elect a pope. The selection process dates back to the 13th century, when indecisive cardinals were locked in a remote monastery for a year, given only bread and water, and told to come out when they had chosen a new pontiff.

These days, the election takes place in the Sistine Chapel and starts two to three weeks after the Pope’s death.

Smoke and mirrors. The cardinals write the name of their chosen candidate on a piece of paper and put it in a silver chalice.

These are then counted, strung together and burned. Black smoke indicates an inconclusive result; white smoke signals a winner.

Lessons in papal democracy.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

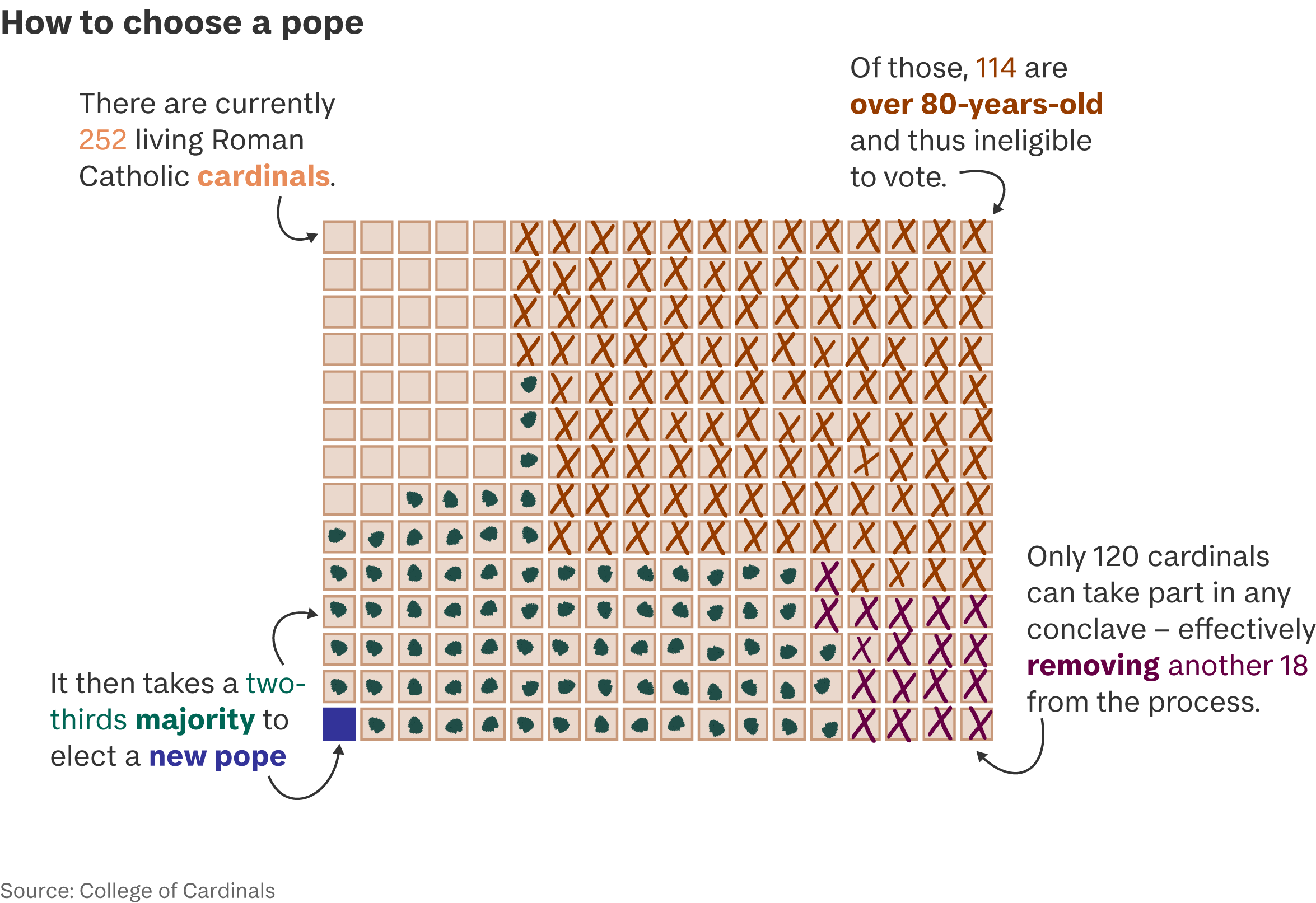

1 – Don’t be too old. There are more than 250 cardinals from 90 countries, but only those under 80 can vote or be elected pontiff. This leaves a pool of between 135 and 140.

2 – No conferring. Voting takes place in strict secrecy, with the cardinals shut off from the outside world and social media hate-mills and love-ins.

3 – Take your time. Voting takes place four times a day until a candidate secures a two-thirds majority, with breaks for rest, reflection and prayer.

4 – But not too long. If no successor is chosen after 33 rounds, the field will be trimmed down to two frontrunners.

5 – Back a willing candidate. It doesn’t happen often, but a winner can reject the papacy, as St Philip Benizi did in 1271 by hiding until another cardinal was elected.

The Dubliner. The man tasked with ensuring a smooth transition is Cardinal Kevin Farrell. His role as camerlengo has drawn inevitable comparisons with Ralph Fiennes’s character in Conclave.

Farrell is an Irish-born former altar boy who runs the Holy See and the Vatican’s supreme court. Or, as the Metro put it, “a bloke from Dublin called Kevin”.

We have a winner. The chosen cardinal will pick a papal name, don white robes, and step onto the balcony of St Peter’s Basilica to address the faithful.

War of the worlds. This year’s conclave could be the largest ever, and one of the most fractious, with conservative cardinals keen to claw back influence.

Diversity. Roughly 80 per cent of the cardinals eligible to vote were selected by Francis, who elevated bishops from under-represented places such as East Timor, Ghana and Paraguay, eroding the stranglehold of the European cardinals.

Many are believed to share his liberal vision. However, this does not guarantee the next pope will be in Francis’s mould. After all, Francis was elected by a group of cardinals appointed by his traditionalist predecessors.

The lack of experience of newer cardinals could also allow a lobby of powerful conservatives from North America and Europe to dominate proceedings.

Runners and riders. Potential popes range from the Vatican’s liberally-minded secretary of state, Cardinal Pietro Parolin, to Cardinal Robert Sarah, an ultra-conservative critic of Francis.

But there is no clear front-runner. One writer on the Vatican points out that Catholicism is rather older than the left-right spectrum, with several axes of papal politics operating on a non-physical plane and three “about being Italian”.

What’s more… The Observer will know better than to make predictions. In 1829, the newspaper described the 84-year-old Cardinal Somaglia as a good candidate for pope on account of being a “very old man”. He lost and died a year later.

Graphic by Katie Riley and Bex Sander.