On the final Sunday of Milan Fashion Week, in September, the musician and composer Ludovico Einaudi walked across the lantern-lit courtyard of the city’s storied Pinacoteca di Brera and took a seat at a grand piano. He was there to play a live soundtrack to Giorgio Armani’s 50th anniversary runway show, during which the design details that have become synonymous with the brand – soft, deconstructed tailoring, a weightless twinkling of organza, beaded bolero jackets and jacquard silks – were paraded by models who walked in the same two-by-two formation Armani had always instructed them to. The mood was sombre: a celebration, yes; but a party, no. A big bash that was meant to have followed the show, planned to take place on an upstairs balcony, became instead a mournful gathering. “Even the thronging around celebrities wasn’t as hysterical as usual,” the journalist Alex Fury, who was at the show, told me recently. Fury sat next to Sir Paul Smith, who, like many of the guests, “reminisced over his encounters with Armani over the years”.

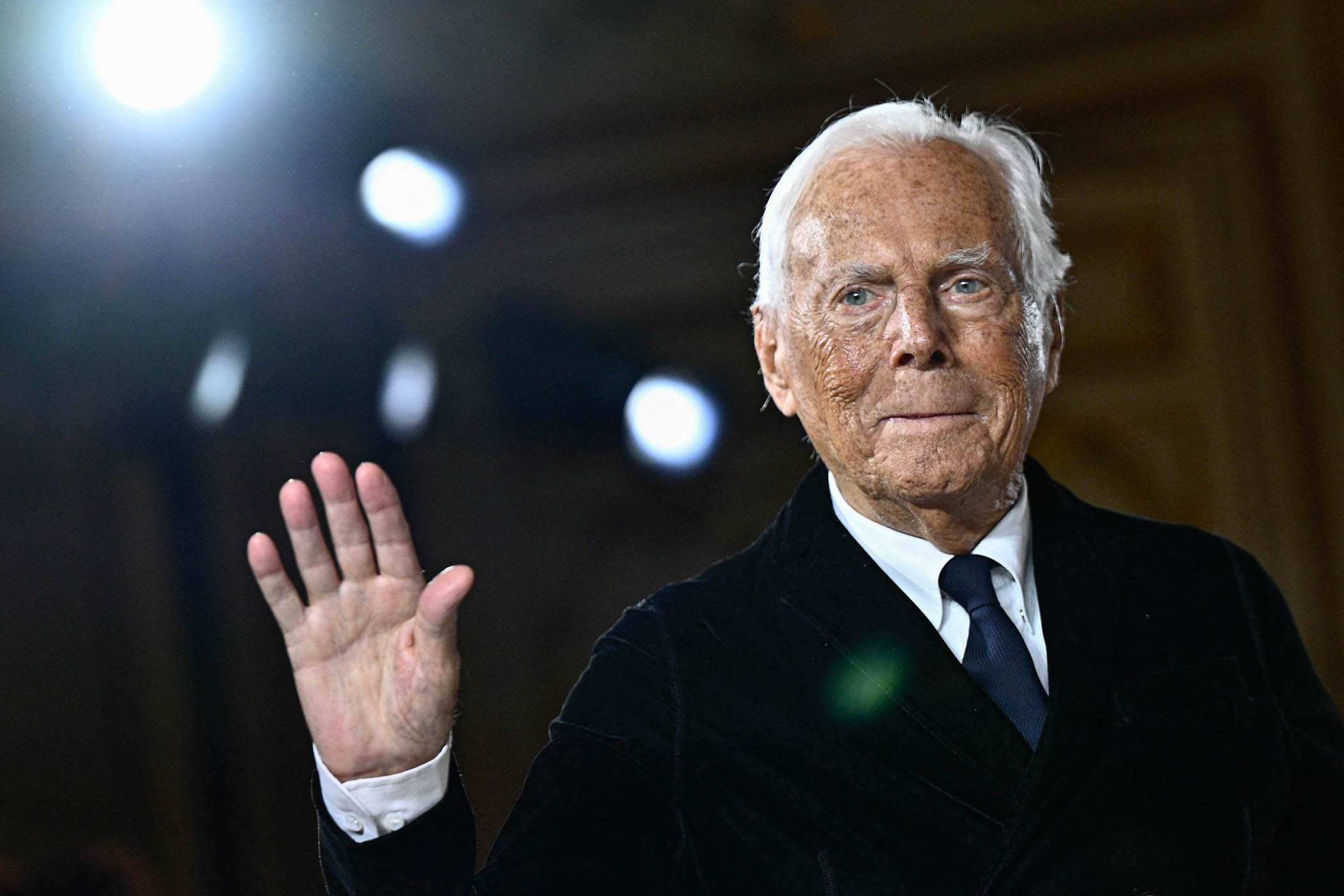

Armani, known respectfully as Mr Armani and affectionately as King Giorgio of Milan, died on 4 September, three weeks before the show, at the age of 91. Rumours of the designer’s declining health had been circulating since June, when for the first time in his career he missed the curtain call at his menswear and haute couture shows. But in Milan, and across the fashion industry, the news of his death still came as a surprise.

Armani was famous for an intimately hands-on approach to his business. Such was the control he exerted over even the smallest details of his empire that fashion editors recall him assigning them the exact same seat at his shows, and models remember him personally applying their eyeliner backstage. During his summer convalescence, he was said to have called members of his team to ask why the Emporio Armani show was running late, only a minute or two after it was scheduled to have begun. (He was watching via live feed.) He also personally invited guests to the 50th anniversary show – a sure enough sign that he expected to be in attendance. And he had signed off on many of the event’s details, from the Armani Casa lanterns, arranged symmetrically around the Pinacoteca’s courtyard, to the food served (elegant bowls of rigatoni pomodoro) and the colour of the champagne (pale gold Ruinart).

The anniversary show lasted for 20 minutes. Afterwards, members of the audience – family and friends, employees past and present, a select group of designers and editors – continued to share memories, some tearfully. Before the event, guests were given a T-shirt with Armani’s face on it, and though the show had a strict black-tie dress code, at least one audience member wore it proudly beneath a formal jacket. When the show neared its end, and visitors reckoned for the first time with the fact that Armani would be making no more curtain calls, there was a “palpable swell of emotion”, Fury said.

Window display: Armani was famous for his hands-on approach to every level of the business

At the time of his death, Armani was founder, president and creative director of all brands under the Armani umbrella. He ruled his empire with an iron grip, seemingly until the end. In 1975, when he famously sold his Volkswagen Beetle to establish his brand, he was 40 and still a relative newcomer to the industry. By the time he died, some 50 years later, he had created a world-famous luxury group that in 2024 made $2.3bn in revenues. “I always appreciated that he was doing something that he believed in, and that it was very successful,” the journalist and fashion critic Suzy Menkes, who has reported on Armani for decades, told me a week after the show. “The thing that made him so special and different from all others was the fact that he was so interested and involved in everything.”

Menkes’s sentiment echoed around the porticoes of the Pinacoteca. But even more pressing questions hung in the air, too: when a figurehead as important and controlling as Armani dies, what happens to the brand they created?

And who takes over?

The Armani succession story is one of the most talked-about in the luxury industry right now, fuelled by the contents of Armani’s will, which was made public on 12 September, just four days after his Milan funeral.

In a move that Italian tabloids branded “a surprise twist”, Armani expressed wishes for his empire, comprising the Giorgio Armani and Emporio Armani fashion brands as well as Armani Casa, Armani Hotels and Armani Beauty (an organisation that employs some 8,700 people in total) to be gradually sold. The will itself was sensational for its detail: an instruction for his heirs to offload a 15% stake in the business within 18 months, and an additional 30% to 54.9% to the same buyer within the next five years,

Purple reign: Armani poses with models on the runway at the end of the Emporio Armani fashion show during the Milan Fashion Week Womenswear Spring/Summer 2024 on 21 September 2023

In the will, Armani divided 90% of the company’s shares between five heirs: his partner, and the head of Armani’s men’s style office, Pantaleo (Leo) Dell’Orco; his sister, Rosanna Armani, an Armani board member; Rosanna’s son, Andrea, who is also on the company’s board; and his nieces, Roberta and Silvana, the latter of whom is the brand’s womenswear director and who recently joined the board as vice-president. (Armani had no children of his own.) The remaining 10% of shares was assigned to the Armani Foundation, which he established in 2016 to guide business management, and which he wished to hold never less than a 30% stake in the company in perpetuity.

Industry analysts have valued the Armani empire at anywhere between €5bn and €12bn – a remarkable sum of money. In the will, Armani appointed Dell’Orco to handle the sale, and stipulated the three luxury conglomerates he would prefer to be considered for ownership: L’Oréal, which holds the licence to market Armani Beauty; EssilorLuxottica, which holds the licence to manufacture Armani eyewear; and LVMH, parent company to Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Fendi, and many more luxury watch, jewellery, wine and spirit brands, and the current title sponsor of Formula One.

All three companies issued statements expressing their gratitude for being considered, and made great efforts to leave the door open for discussions. Bernard Arnault, chairman of LVMH and its chief executive, and one of the richest men in the world, described Armani as “a true genius” and “the only great couturier, along with Christian Dior, who built and led a global brand in terms of both style and industry”, before adding that, should their companies end up working together, “LVMH would be committed to further strengthening Armani’s presence and leadership around the world.”

While the contents of Armani’s will came as a surprise to the fashion industry, a source close to the brand told me that it was “unlikely” to have been news to the family and Armani’s closest confidants. (The Armani family declined to offer comment, and recently appointed a new group CEO, Giuseppe Marsocc, who has spent the past five years as head of Armani America.) “It wasn’t just something he did over coffee one morning,” said the source, who preferred not to be named. “He thought long and hard about it. He was very specific.” Nevertheless, intense speculation has begun. Before Armani’s death, it was widely assumed that the brand would remain under the ownership of the Armani family, a personal point of pride for the man himself, who managed to retain sole control of the company during his lifetime. In 2023, he told the Observer: “What worries me [within fashion] is the proliferation of ever-larger conglomerates and the transformation of fashion into a form of unrestrained or purely visual entertainment.” That he decided his empire should be sold to one such conglomerate, only a couple of years later, seems shocking to many.

Soldier days: Armani spent three years in the department of medicine at the University of Milan and then suspended his studies and registered for the military, working as a medical support officer at a hospital in Verona

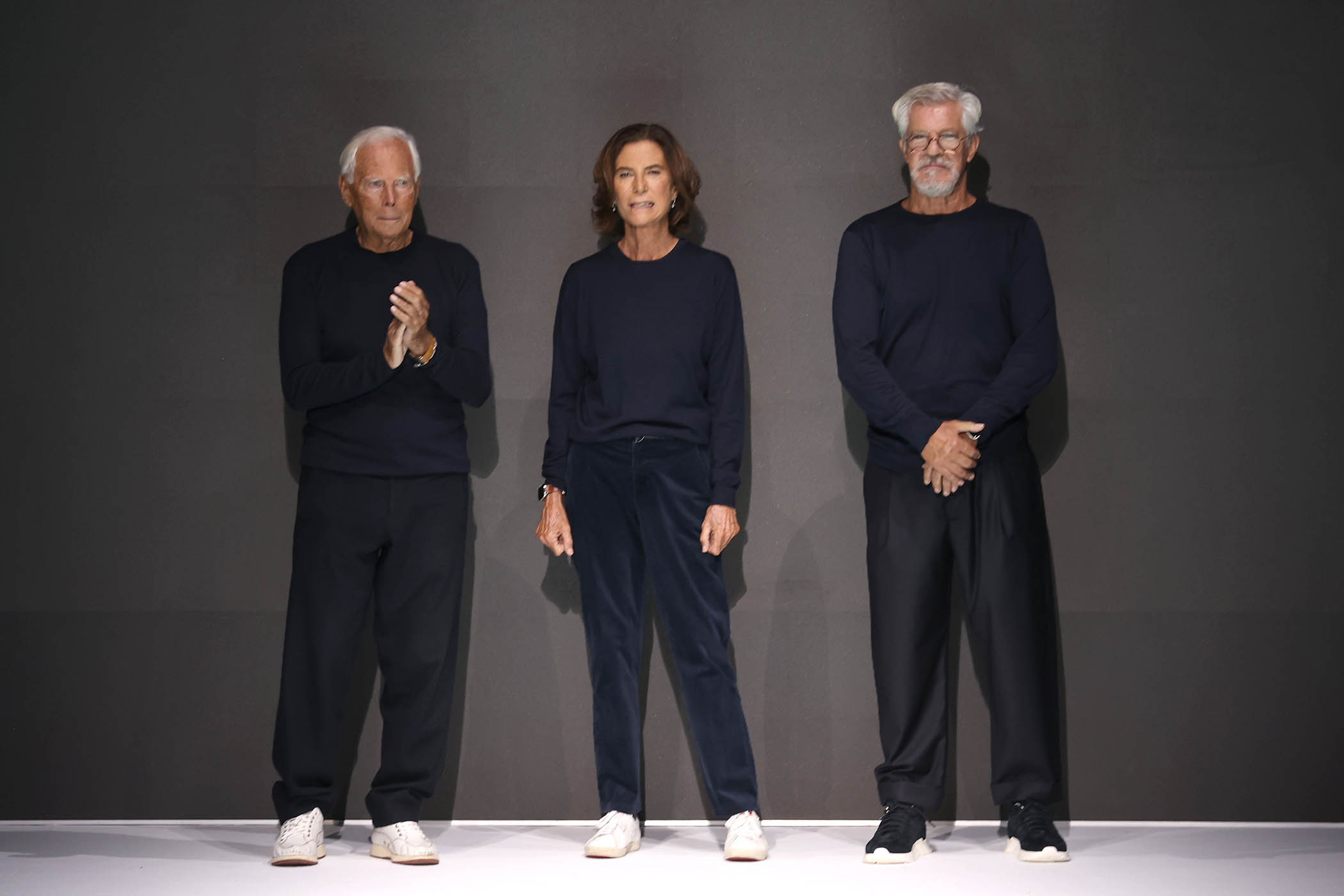

In the weeks before he died, Armani told the Financial Times: “My plans for succession consist of a gradual transition of the responsibilities that I have always handled to those closest to me,” a statement that seems at odds with the desire expressed in his will to sell more than half of his business to an external buyer. It is assumed that the brand’s fashion collections, at least, will continue to be designed by Dell’Orco and Silvana, who worked side-by-side with Armani for years. Over the past two years, the designer frequently took his post-show bow alongside the pair, signalling that he was positioning them as his creative successors. When Armani did not appear at his final men’s shows in June and haute couture show, in July, Dell’Orco and Silvana took the bow without him. At the Pinacoteca, they appeared together hand-in-hand, and received a standing ovation.

Armani was born in 1934 in Piacenza, a town in northern Italy, the second child of parents Ugo Armani and Maria Raimondi. He enrolled in the department of medicine at the University of Milan, but three years later, in 1953, he suspended his studies to register in the military. In 1957, he became a window dresser, and later a sales adviser and a buyer, at La Rinascente, a high-end department store in Milan, before designing menswear for Nino Cerruti. He met Sergio Galeotti, a young apprentice architect, in 1966, and together they formed Giorgio Armani SpA. Their first men’s and womenswear collection was presented in 1975.

It is hard to overstate Armani’s importance and influence within the fashion industry, and the esteem in which its members hold him. “He totally remade menswear,” Menkes told me. “What they wore, the way they felt about clothes.” Though he also changed fashion for women, notably through the soft-power suit, “for men it was a complete revolution. Everybody on the masculine side felt life had changed. It was more palatable, more wearable, a different world.” During the 1980s and 1990s, he designed costumes for some 200 films, including American Gigolo, The Bodyguard, Goodfellas and The Wolf of Wall Street, bringing his clothing to a mass market, and he was the first designer to dress celebrities for the red carpet. Nick Sullivan, creative director at US Esquire, told me that Armani’s initial success lay in creating a “status-driven fashion that wasn’t old money but also wasn’t brash – whereas the rest of the 1970s and 1980s was”. (Sullivan describes the Armani look as “scrupulously tasteful, in a modern way”.) Of Armani’s focus on Hollywood, Sullivan told me: “There were a lot of people who don’t own any Armani, but know what it stands for because they saw it on the red carpet.” The practice of dressing red-carpet stars is common for brands now, but “others didn’t pick it up until we reached the social media age”.

Throughout his life, Armani committed wholly to the design principles of elegance, simplicity and timelessness. Towards the end of his career, his runway shows became less progressive, and they no longer led conversations on the catwalk. When the industry turned its attention to the loud logos, PR stunts, celebrity designers and hype products that dominated most of the 2010s, Armani’s refusal to engage resulted in a quieter period. For much of that decade, his shows, held religiously in the same Armani-owned venues, made fashion headlines not for the clothes on the catwalk but for the celebrities on the front row. Armani’s runways were always scheduled for the last day of Milan Fashion Week, by which time some of the industry’s editors had already flown to Paris for the next round of collections. Those who stayed did so out of respect – and never expected a spectacle. One editor told me that such was the sameness of Armani’s shows, and the warmth of the rooms in which they took place, that they sometimes fell asleep halfway through – though they were at pains to add that this happens at other shows, too. Another longtime fashion journalist told me: “It’s hard to think of a designer who wouldn’t have been critiqued for delivering the same clothes every season.” Editors never questioned the quality of Armani’s clothing – his final two collections were widely considered some of his best – but they quietly wondered how they might resonate with modern-day consumers beyond diehard brand devotees.

Walk of fame: Armani at the One Night in Venice runway show on 2 September 2023 in Venice

In some ways this sameness was part of the Armani charm. “Armani is one of the few labels you can rely on to look good on all subjects,” one editor told me. Claudia Croft, editor of 10 Magazine, said after the show that Armani “really served his customers” and “It was hard to criticise him. He was so true to himself – his standards were very, very high. He had this absolutely clear vision of what he wanted and how it should be done, and that’s what propelled the brand for the past 50 years.”

Dell’Orco and Silvana may be holding the creative reins for now, but no comment has been made about future creative stewardship. If a new creative director takes over, many in the industry will see it as a positive evolution. Lucie Greene, founder of brand and trends consultancy, Light Years, told me: “On one hand, Armani’s image and persona is indelibly tied up with the brand, but on the other, he managed to create a clear set of universal design principles and a distinct aesthetic that are timeless and could easily live on, under the right leadership.” She adds that Armani created “a playbook philosophy that in many ways transcends him”.

Sullivan told me that, in the right hands, “You could move the Armani brand forward and still pay absolute reverence to what Armani did consistently”, but that “It might take that change for the scales to fall from certain people’s eyes and see it for what it is.” He went on, “We’re distracted from design a lot of the time, and change here might actually just give people a chance to refocus, become reacquainted with what Armani represents.”

Several editors suggested to me that any creative director replacement would need to be a visible appointment, rather than a behind-the-scenes name, to avoid the “Donna Karan and Calvin Klein effect, where the brands eventually felt licensed and anonymous once their namesake stepped away”. Croft, Green and Sullivan all pointed to the recent appointment of the Colombian-born French designer Haider Ackermann at Tom Ford as a blueprint for a way forward. “Ackermann is highly respected and known in his own right,” Croft said. “And he is injecting new vigour and creativity into a brand while also making clothes and staging shows that are undeniably Tom Ford in cues, attitude and spirit.”

“Fashion creative direction has become like Premier League football,” Sullivan told me. “If you’re David Beckham, eventually a team will buy you and you’ll play football for the other team, and some fans will go with you and some fans will stay with the original team. But the bottom line is, you’re a commodity. Someone like Haider is different. He does things his own way at a super-rarefied level. Armani will want to make sure it’s a true designer like that who takes over.”

When Armani nominated LVMH, L’Oréal and Essilor-Luxottica as potential buyers, he caused a stir within broader fashion circles in Italy: all three companies are French. (EssilorLuxottica has offices in Paris and Milan.) A guest at the 50th anniversary show, who preferred not to be named, told me: “There is a strong sense that it should be an Italian company that buys it. Armani was so proud of being Italian and Italy is fiercely proud of him.”

At a recent press conference held by Camera Nazionale della Moda, the Italian fashion industry governing body, its chairman, Carlo Capasa, emphasised to a group of luxury CEOs the importance of promoting Italian fashion and brands. At the same event, Lorenzo Bertelli, Prada’s CEO, admitted that he would be disappointed if Armani were sold to a foreign brand. “Of course, it was his company,” Bertelli said, “and I can only respect his will. But I would be upset to see it in non-Italian hands.”

Menkes told me that Armani would have considered all his options. “I don’t know how easy it is to find the right person in Italy,” she said. “It’s not that I think people can’t do it in Italy, but that everything now is so incredibly difficult. You need enormous amounts of money, of staff, all the rest of it. Maybe Mr Armani felt he needed someone big and strong enough to keep his business going.”

Triple force: Giorgio Armani with Silvana Armani and Leo dell'Orco at the end of the Milan Fashion Week show in 2021

Menkes said she “never talked to him personally about how he felt about getting older, so I didn’t know what his plan was”. But: “I imagine he thought a lot about his staff. He had so many people working for him. He’ll have wanted them to keep their jobs.”

There is little precedent for what happens next. Other Italian fashion houses – notably Gucci, Valentino and Missoni – have taken on investment or been bought by a conglomerate. But each has moved in a different direction, with varying degrees of success. And the recent sale of Versace to the Prada Group has yet to bear fruit.

Menkes told me it was difficult to know how successful a deal would be. “You can be told someone is doing tremendously well,” she said, “and five minutes later they’re going out of business.” But Sullivan thinks this has the potential to be a great moment for the brand. “The master is gone,” he told me, “but all of his works are still there. It can go to a new and different place.”

Armani himself always seemed to know which way forward would be best. “The only way to push boundaries is to keep looking at the world, at the evolutions of society, and act inventively,” he once told The Observer. “Fashion is always a reflection, and at times also an anticipation, of the moment.”

Mr Armani: the timeline

Family matters: (from left) Giorgio with his sister Rosanna and brother Sergio

Giorgio Armani was born in the northern Italian town of Piacenza in 1934, as the second child to parents Ugo Armani and Maria Raimondi.

Armani enrolled in the department of medicine at the University of Milan. However, after three years he suspended his studies and registered in the military in 1955.

After his military service in the early 1960s, Armani began his career in fashion as a window dresser, sales advisor and buyer at La Rinascente in Milan, later designing menswear for Nino Cerruti’s Hitman.

In 1966, Armani met his late partner Sergio Galeotti, a young apprentice architect. The duo formed Giorgio Armani SpA and in 1975 presented an inaugural menswear and womenswear collection.

At the 50th Academy Awards, held in 1978, Diane Keaton made history as the first actor to wear Armani on the red carpet.

The 1980 film American Gigolo catapulted the brand to fame when Richard Gere’s character opens a drawer filled with Armani shirts - all carefully folded with their logos on full display. Throughout the film he wears the brand, including a signature relaxed suit.

Julia Roberts made news headlines when she wore a grey men’s Armani suit to the 1990 Golden Globes. She won the award for best supporting actress for Steel Magnolias.

Armani was the honorary chair at the 2008 Met Gala and was joined by co-chairs George Clooney and Julia Roberts. The theme was Superheroes: Fashion and Fantasy and celebrities such as Beyoncé, David and Victoria Beckham attended wearing Mr Armani’s designs.

In 2010, Lady Gaga wore Armani Privé to the Grammy's. This developed a partnership that led to the designer making the costumes for her 2011 Monster Ball tour.

Armani received the outstanding achievement award in London at the 2019 Fashion Awards, which he was presented with by Cate Blanchett and Julia Roberts. Throughout his career he also won the Legion of Honour and Compasso d'Oro Award.

Armani received a five-minute standing ovation at his One Night In Venice runway show in 2023. The event was a celebration of the 80th Venice International Film Festival and Armani’s enduring affinity for the movie industry.

Armani was reportedly only absent from three shows throughout his entire career, the Armani Privé AW25 haute couture collection and both shows during the SS26 menswear season. He died on 4 September 2025, at the age of 91.

Photographs by Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy