One day last autumn, Nicky Onsloe was driving through Trafalgar Square in central London when the exhibition Francis Bacon: Human Presence at the National Portrait Gallery caught his eye. He’d heard stories about Bacon from his father, Ted, who used to own a gambling club in Soho in the 1960s. He phoned his dad. “Wasn’t that the bloke you used to know?” he asked him. His call set in motion a chain of events that solved a mystery that had defeated art historians for half a century. Whatever happened to Ted Westfallen?

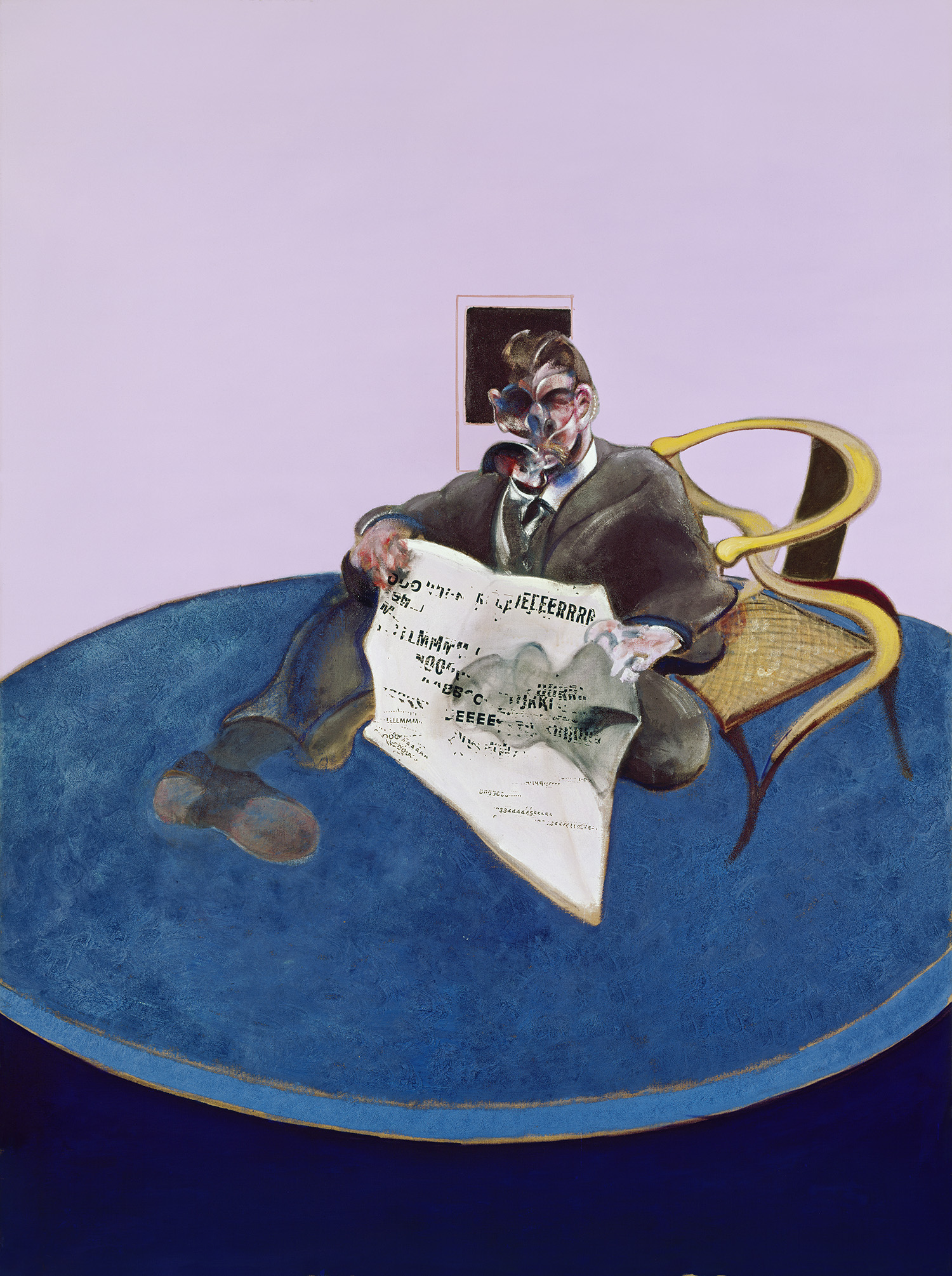

A bouncer and former meat market porter from the East End of London, Westfallen was the model for a painting, Study for Portrait, by Francis Bacon more than 50 years ago. Westfallen had rescued the artist from a beating on the doorstep of his club in Soho and the two became unlikely friends. Bacon’s portrait of Westfallen, made in 1969, is in a private collection today, but if it ever came to market it would undoubtedly fetch tens of millions of pounds.

The artist died in 1992 and only half a dozen of the people who he painted are still alive today, Mick Jagger among them. But the soaring interest in Bacon and his work following his death failed to throw up any clues about the whereabouts or fate of Westfallen, who was also known as Ginger Ted and Red Ted on account of his hair colour. Art historians impatient to fill in the blanks about the painter searched for him in vain. There were no leads; perhaps he was dead. But now an implausible turn of events worthy of Bacon’s own often rackety life has resolved this mystery.

Westfallen had kept letters and photographs from his years with Bacon. His son put them together and showed them to the National Portrait Gallery. But the gallery encouraged him to take them to the Bacon estate instead. The memorabilia was immediately recognised as a bonanza by Martin Harrison, a tireless art-world gumshoe who has spent years trawling the dives of old Soho and interviewed its surviving denizens in the hope of finding a trace of the lost sitter, but came up empty-handed. Harrison said: “Ted got out of the game. He went straight. I assumed he’d died.”

But Ted Westfallen is very much alive, living near Thurrock in Essex, and remembers his time with Bacon clearly. “Francis always knew exactly what he was doing,” he told me last week. “I saw him once in Muriel’s, the Colony Room, with a whisky. I was keeping my eye on him, and I saw him throw the scotch on the floor – the glass came up empty. The idea was – I’m sure of it, I could read him like a book – that he liked to see people pissed. He wanted to see you through his eyes, see how you were, but if he was drunk, he couldn’t register it. He would go in a pub and sit and look at whoever it was just to see the characters of people.”

Almost single-handedly, Bacon saved figurative painting from the chokehold of abstract art in the 20th century. But the painter was as well known for his riotous and ramshackle lifestyle as for his work. One of the celebrated characters of postwar Soho, he mixed with aristocrats and gangsters, dividing his time between intense bouts of work at his paint-splattered studio and the casinos of the West End.

Bacon’s posthumous prices have astonished the art market. Three Studies of Lucian Freud, Bacon’s triptych of his one-time friend and fellow painter, fetched £90m when it was sold in 2013, a record for an artwork. But the artist was impatient with canvases that displeased him, often taking a blunt instrument to them. Others he simply forgot about. The deep-pocketed Estate of Francis Bacon has, since his death, embarked on a worldwide trawl for undiscovered stories about the artist. Fittingly, it was a stroke of luck no more than the flick of a playing card from the former gambling dens of Soho that led to Bacon’s long-lost sitter.

Ted at his home in Thurrock, Essex. On the table, memories of his friendship with Bacon

Ted Westfallen is 82. No longer ginger, he’s white-haired and bespectacled, but still a well-set man. He lives an hour’s drive from his old manor. When we speak, he is wearing an old-school football shirt in the colours of West Ham United. He now goes by the name of Onsloe – one of the reasons that he eluded Harrison’s sleuthing for so long was that he changed his name by deed poll. After his years with Bacon, he went into business with his brother Ronnie, selling cars in Essex. “Ronnie changed his name to Onsloe, with an ‘e’,” he says. “He saw it written down somewhere and liked it. And he said to me: ‘You should change your name too, Ted. The Old Bill out here knows you as Ted Westfallen.’” Westfallen says he spent time in the “boob”, or prison, for GBH and affray.

Related articles:

He recounted his first meeting with Bacon. Like so many other important episodes in the artist’s life, it happened in Soho, which wasn’t the proudly rainbow-emblazoned quarter of bubble tea houses and editing studios that it is today. It was a rookery of strip clubs, clip joints and shady spielers, or out-of-hours drinking dens. Westfallen was 25, and not long out of Wormwood Scrubs. His uncle, who he describes as “a villain in the West End”, got him a job on the door of a gambling club that was on the wilder shores of respectability. Westfallen could size up guests through a peephole before deciding whether to admit them or not. This spyhole had a role in a game of cat and mouse played by the police and the doormen, he says. “When the Bill used to come and raid us, they put their hands over the hole so we couldn’t see who it was, so I used to light a cigarette and burn their hands. I’d go: ‘Sorry officer, obviously I didn’t know it was you!’ And they said: ‘You bastard! We’ll have you!’”

One geezer had his elbow up at Francis. I thought, Oh, they’re mugging him

One geezer had his elbow up at Francis. I thought, Oh, they’re mugging him

Bacon, who was in his late fifties, gambled at the club one evening with his friend, the painter Denis Wirth Miller. Westfallen said: “After they left, I went out to see everything was kosher, and I saw Francis and Denis with three geezers in their twenties. One of them had his elbow up at Francis. I thought, ‘Oh they’re mugging him,’ so I shot back to my cubbyhole, I took out my little truncheon, I ran down the stairs and I went ‘pop!’ – caught one of them on the back – and ‘bang!’ – another one – and they ran away crying.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

“About an hour later the buzzer went and there was Francis on his own. I said: ‘Do you want to gamble?’ He said he’d like a coffee, so I got him one. Out of the corner of my eye, I could see he was looking at me all the time. I thought to myself, that’s a bit strange. Another gambler said to me: ‘Ted, you know who that is, don’t you?’ I said: ‘No.’ He said: ‘It’s Francis Bacon, the painter.’ I thought he meant painter and decorator.”

Bacon wanted to repay Westfallen for seeing off his attackers and offered to treat him to a fish lunch. “I thought he meant rock or eel,” says Westfallen. In fact, the pair tied on a bib at Wheeler’s, the noted fish restaurant, before Bacon introduced Westfallen to the bohemian drinking club of the Colony Room.

The pair became the odd couple of Soho, a relationship that anticipated Minder, the popular TV comedy of a decade or so later, with Bacon, a one-time shoplifter, cast in the role of the chancer Arthur Daley, and Westfallen as Terry McCann, his gruff but kindly protector. Westfallen looked out for the older man, warning him off the moody boozers where he liked to sit for hours over a drink watching the regulars. “I used to say to him: ‘Mile End at night isn’t the same as Knightsbridge, Francis.’” In return, Bacon made sure that Westfallen always had a few quid. One of the quirks of the inveterate gamblers Bacon and Freud was that they preferred to lose whenever possible, a spur to get back to work in order to sell paintings and make good their losses. Westfallen remembers Bacon ignoring his advice to avoid one of the less transparent games of chance offered at his club, only for the artist to shock the house by winning £3,000 – a huge sum in the 1960s. “They gave Francis his winnings but he said: ‘No, leave it for the boys.’”

Ted and Bacon in Paris, where they shared a toast with Georges Pompidou, the French president

Pictures from Ted's archive, including him and Bacon at a Soho nightclub along with its owner

Bacon took younger men as lovers. One of them was George Dyer, a petty criminal. They met when Dyer broke into Bacon’s studio in South Kensington, while the artist happened to be there. Westfallen was Bacon’s type, but he insists they never had a sexual relationship. “He tried it on once or twice. One night, he’d had a drink and he said to me: ‘Ted, if you come and live with me I’ll give you all my works.’ I said: ‘Francis, you know I’m not like that.’ And he looked at the floor and went: ‘I know’. I could have been a millionaire!”

Westfallen had no idea that Bacon was painting him. The artist liked to work from photographs. The younger man had given him pictures of himself taken in a photo booth. “Personally, I thought that compared to the other stuff he’d done, the one of me wasn’t a bad picture. Francis told me that when they invented photography, paintings went out the window. He said: ‘I can only paint people I know. And when I paint you, I paint the inside of you.’ I think my picture’s in the south of France somewhere now.”

Compared to the other stuff he’d done, the one of me wasn’t a bad picture

Compared to the other stuff he’d done, the one of me wasn’t a bad picture

Westfallen accompanied Bacon to Paris, where he was planning an exhibition. They met Georges Pompidou, the president of France. “We were all having a toast. It came to my turn and I couldn’t speak French so I just said: ‘Cheerio!’ Pompidou couldn’t stop laughing and his shoulders were going. When we left, Francis said to me: ‘You made a big impression on him.’ I said: ‘I was copying you, Francis. That’s what you say all the time when you’re pissed: you go, Cheerio!’ He said: ‘I don’t, do I?’”

The two attended a party at a townhouse in Chelsea belonging to the Duke of Devonshire. “There was an old boy coming up the stairs on two walking sticks. It was Harold Macmillan. Francis said: ‘Mooch around, Ted, you might find it interesting.’ I went into a room full of pictures. A little tubby fellow was there. He said: ‘Excuse me, are you a painter?’ I said: ‘No, mate. I’ve got a gambling club in Soho, a nice little gambling spieler.” He went: “Oh Soho, how exciting!’

“Francis told me: ‘He’s Sir John Betjeman, the poet laureate.’ I said: ‘Cor, I thought I recognised his boat!’ Lovely man he was, and all.”

Westfallen said he’d had enough of the party. “Francis said: ‘The Krays would give anything to be where you are. They’ve been trying to get in with this crowd for years and I’m giving it to you!’ I said: ‘I’m not the Krays. I’m a working man! You’re talking about villains there – nah, that’s not me.’”

But Westfallen was familiar with criminals and their world. One day a letter arrived for Bacon and Westfallen recognised it immediately as “a nick letter”: sent from Parkhurst prison. “It was from Ronnie Kray. He said: ‘Dear Francis, I hope you don’t mind, I’ve got a writer doing a biography of me and Reggie and when I told him I knew you, he said he would love to meet you. Is it possible to make a meet? I hope everything’s OK, Francis. God bless, lots of love, Ron.’ I thought, he’s like a little boy and the writing was terrible. He couldn’t spell, but that was Ronnie Kray.”

“Francis said: ‘What do you think of that?” I said: ‘I’ll put it in me pocket.’ A few days later Francis said: ‘Have you still got it?’

“I said: ‘Yeah, what’s up?’ He said: ‘Oh give it back to me please. I’ve got to get rid of it.’ I said: ‘What’s the matter?’ He said: ‘Well I don’t want it to fall in the wrong hands.’ Because the Krays were all over the papers at the time.”

Westfallen came to blows with Dyer after the latter interrupted a meal he was having with Bacon in Wheeler’s. “He wanted some money. Francis said: ‘But I gave you three grand two weeks ago! Have you spent it all, then?’

“I said to Dyer: ‘Look mate, we’re eating dinner, do us a favour and go away.’ And he come right up to me and he said: ‘You must be flavour of the month!’ He said: ‘Outside!’

“So we went outside and as he’s come out the door, there was a metal cage over an extractor fan, he grabbed it to swing at me but it wouldn’t come off. So I gave him a slap: ‘Crack!’ He went down like a sack of shit. I said: ‘Go and piss off, mate, we’ve all had enough of you.”

On the eve of a major exhibition of Bacon’s work in Paris in 1971, Dyer was found dead on the toilet in the artist’s hotel suite. According to Westfallen, Bacon believed it was an act of spite to overshadow his success. “He said: ‘That bastard, he done it on purpose.” I said: ‘Nah.’ But he went: ‘I’m telling you, he done that on purpose. He waited till the show and then he committed suicide.’”

Westfallen looks back fondly on his days with Bacon. “It was marvellous, the best time of my life. I was eating the best food in the world. Francis taught me how to eat, he taught me about wine. A friend of mine said to me: ‘He’s immortalised you, Ted.’ And I said: ‘Yes, course he has.’”

The Holmes-loving historian on bringing home the Bacons

by Tim Adams

Francis Bacon in a shot taken by Jane Bown in his studio, 1980

The art historian Martin Harrison first started working with the estate of Francis Bacon for his 2006 book In Camera, which traced, in forensic detail, the many photographic and ephemeral influences on the painter’s work, from murder scene snapshots and war reports to Silk Cut adverts - the things that Bacon would hoard and surround himself with in his Kensington studio. Harrison was invited after that to create a definitive catalogue raisonné of the artist’s often chaotic output. That process took 10 years. It has been followed by a fascinating series of books, edited by Harrison, which have created the field of “Bacon studies”.

Speaking to me last week, about the Ted Onsloe discovery, Harrison suggested that the work has been all-consuming. It has also satisfied a curiosity that began for him in art college. “I remember the first Bacon I saw, Landscape near Malabata, very clearly. And I remember thinking: What the hell is this? I was 16 or 17. I knew it was the work of a genius, but in my stupid little teenage head, I couldn’t begin to understand it – but I wanted to try.”

Over six decades, Harrison hasn’t lost that curiosity. “It always starts and ends with a painting,” he says. “But also when I was a kid I used to love Sherlock Holmes and I wanted to be a detective, so I am as much that as anything else. There are 584 extant Bacon paintings. I always said to find the first 500 was not so difficult, but the other 84 – that’s the challenge. We were right on deadline for the catalogue when I located the last one.”

Harrison was not helped in that quest by the fact that Bacon had no interest in any kind of record keeping. All that was done for him by the legendary Valerie Beston - “Valerie at the gallery” as Bacon called her – who worked for his dealer Marlborough Fine Art and who for 40 years heroically tried to impose some order on his ramshackle life. By the time Harrison became involved, Miss Beston, as she liked to be known, was infirm with Alzheimer’s, but he was allowed access to the archive of receipts and hotel bills and her meticulous record-keeping.

In among these documents, Harrison had come across some correspondence she’d had with Ted Westfallen, a known friend to Bacon. “Miss Beston had been in touch with Ted about this particular painting [Study for Portrait, 1969] in 1971 at the time of the Grand Palais show of Bacon’s work in Paris. The painting had been part of that show, but Ted didn’t go, so she had sent him a catalogue.” When Harrison documented that portrait of Westfallen with the newspaper, he did as much as he could to track down what had happened to Ted, searching for the Westfallen name in phone books and census records, but couldn’t find anything. The last he had heard from many of his Bacon contacts was that Ted had “gone straight and become a cab driver”, (which was one job for a while) so he put that in his note to the painting.

When Ted’s family got in touch with the Bacon estate before Christmas, Harrison couldn’t have been more excited. “It was Nicky Onsloe’s girlfriend, Jenni, who sent us an email,” he says. “I was straight back to them.” He could hardly believe the news. “There are only five other living sitters for Bacon paintings and here was another – from 1969! – and with a story to tell.”

Harrison and his wife visited Ted Onsloe at his house near Thurrock – “very industrial Essex” – just before Christmas. “He’s in his eighties now, but you still wouldn’t mess with him,” Harrison says. “He’s a charming bloke. I joked with him: ‘Ted, I can call you a dozy fucker now and you won’t hit me’; he said: ‘You wouldn’t have said that 30 years ago.’

“He obviously was close to Bacon – and they lived the high life. When we were driving there, I thought, crikey, we ought to take a bottle. We stopped at a Co-op and bought the most expensive red wine they had – £14 or something. When I gave it to Ted he took a look at it that said: ‘Why have you brought this shit?’ He learned about wine from Bacon. We have done a little film with Ted for the estate and naturally he asked for seafood, champagne; we sent him a fabulous limo to collect him. Midnight blue with red leather seats. It was what Francis would have done.”

Harrison’s latest volume of Bacon studies, Francis Bacon Retrieved: Lost Words/New Writing, is published by the Estate of Francis Bacon Publishing and Thames & Hudson

Photographs: Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait, 1969 © The Estate of Francis Bacon / DACS 2025; studio portrait by Jane Bown