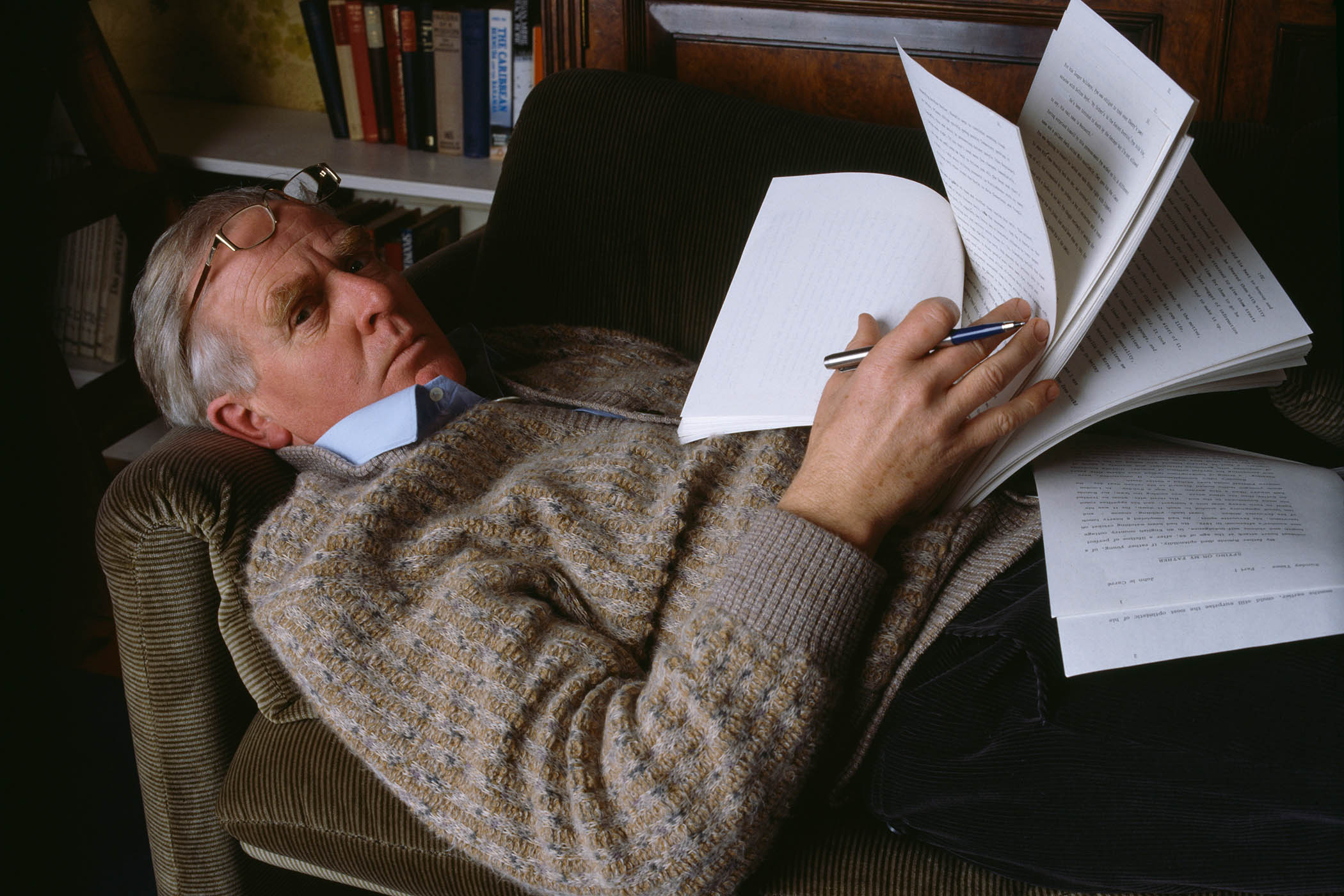

As an Oxford don with a special interest in the Russian mafia, Federico Varese could hardly have been surprised when a figure with links to MI5 offered him a job. Isn’t that how the secret service has always recruited? But when the letter reached Varese, who was on a research trip in Siberia, it wasn’t signed with an enigmatic monogram – an “M” or a “C” – but by the spy who came in from the cold himself, John le Carré, AKA the former agent David Cornwell.

The author of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and The Little Drummer Girl suggested a lunch. This turned out to be like a set piece from one of le Carré’s books, at a Lebanese restaurant in Oxford “opposite the synagogue in Jericho” in the north of the city. Varese recalls: “I am a stickler for punctuality, but I found my host already waiting for me, with his back to a wall, in a distant corner of the restaurant. The waiter seemed to know him well…”

Le Carré, who died in 2020, wasn’t, it seemed, trying to “turn” Varese into an asset, but wanted his guidance on a new book. He said it was “a novel that touches upon the Ossetian-Ingushetia conflict and predicates that part of it is being fought out between rival factions in the west”. Varese gladly accepted a role as le Carré’s collaborator on what became Our Game (1995).

The academic furnished the author with pages on everything from the brand of cigarettes that le Carré’s Russian villains would smoke (“either Prima or Belomorkanal”) to the way former communists might smuggle money out of the Soviet Union after its collapse. As Varese tells me on the phone from Armenia, where he has been spending the summer studying the grandiose headstones of late mafiosi, he was also responsible for rewriting the climax of the book, even though he was “a 29-year-old Italian student with a wobbly knowledge of the English language” at the time.

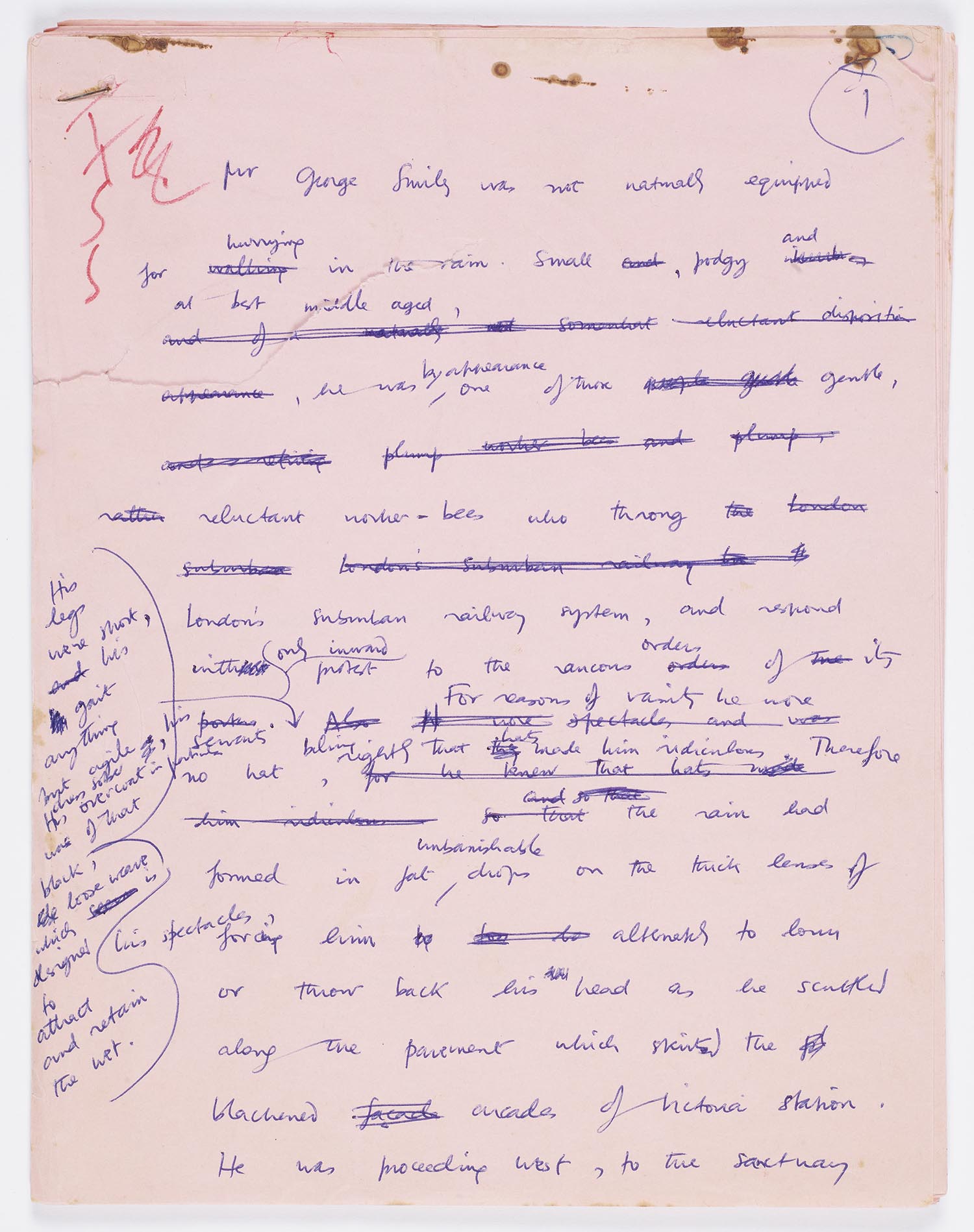

A handwritten draft of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, introducing the ‘podgy’ George Smiley, is on display at the exhibition

In Our Game, a disillusioned spy named Cranmer goes to Moscow in pursuit of the charismatic Larry Pettifer, the agent he’s running. In le Carré’s original draft, Cranmer’s motive was recovering money that Pettifer stole, but Varese suggested a better ending would be that Cranmer wanted to become his dashing rival. The novelist knew a good twist when he saw one and wrote to Varese: “I pinched unashamedly your beautiful formation.” It was by no means the only time that the great writer “pinched” ideas.

Le Carré was one of the most distinctive voices in British fiction, influenced by writers including Joseph Conrad and Graham Greene, but unmistakably sui generis. If that made readers think the novels were “all his own work”, however, an exhibition based on the papers he left to the Bodleian Library provides a fascinating corrective.

John le Carré: Tradecraft, co-curated by Varese, reveals that the books were written with the help of a wide network of friends and fellow writers, as well as professors, journalists and others.

Our secrets don’t long outlive us, and in the five years since le Carré’s death, his many fans have learned more than they perhaps wished to about his strenuous and complicated love affairs – a clandestine life in itself. Now, from the cloistered hush of the Bodleian, comes the news that his writing wasn’t quite all it seems, either.

He was unarguably the author of his books but others also made a vital contribution to these much loved bestsellers: mostly unsung, until now.

The exhibition includes drafts of his novels – typed up by his wife Jane and scribbled over in the author’s hand – as well as an early description of his best-known character, George Smiley of “the Circus”, the closest thing to a conscience in the friendless world of his espionage stories: “legs short … small, podgy” and “middle aged”. There’s also an index card recording details of Cornwell’s time as an undergraduate that refers to his colourful father, Ronnie: a conman and bankrupt, among other things.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Dr Jessica Douthwaite, the other curator of the exhibition, says: “Ronnie wanted both his sons to get good educations and become lawyers, so that they could shield him for the rest of his life. So David had this very strange life as a young man, attending elite institutions, private school and Oxford and then spending the holidays with Ronnie hanging out with gangsters.” Douthwaite claims that the exhibition consolidates le Carré as a “world writer”, not defined by his work on the cold war alone; as a painstaking researcher and a figure at the centre of a web of contacts and sources. They were as crucial to his writing as moles and double agents were to the spying he was once involved in.

Michela Wrong, the author of several acclaimed books about Africa, including In the Footsteps of Mr Kurtz, about the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in the time of president Mobutu Sese Seko, was among le Carré’s collaborators. If one of Smiley’s vigilant “lamplighters” had been keeping tabs on the pair of them, he would have recognised a familiar MO; it all began with lunch at “one of those old-fashioned, white-tablecloth, Mayfair restaurants”, says Wrong.

They were as crucial to his books as moles and double agents were to his spying

They were as crucial to his books as moles and double agents were to his spying

Le Carré, by now in his mid-70s, wanted her help with a novel set in the DRC, eventually published as The Mission Song (2006). Wrong had mixed feelings. She had read a previous le Carré with an African setting, The Constant Gardener, and found it “pretty weak. The colour was lovely but I wasn’t convinced. But the opportunity of working with one of the leading novelists in British literary history isn’t something you’re going to turn down,” she says.

She agreed to look at le Carré’s work in progress and sent him pages of notes in return. She didn’t like his love scenes involving the main character, Salvo, the illegitimate son of an Irish priest and a Congolese girl. “They struck me as stilted and overwrought. I was originally wary of saying as much. To criticise a writer’s romantic musings is surely to criticise their entire approach to the opposite sex, and that rarely goes down well.” But le Carré asked her: “Which passages, exactly? Give me the page numbers.” The scenes were excised from his next draft. “No sentimentality there: he killed his darlings without hesitation,” Wrong says.

Le Carré prided himself on the authenticity of his books and had learned a painful lesson when he visited Hong Kong after setting sections of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy there. The cause of his distress, of all things, was a newly built tunnel in the territory that he hadn’t been aware of when he was writing. His protagonists would surely have used this rather than the more laborious passage by boat.

According to Wrong, le Carré suggested “a research trip” to her. The idea was to go to Bukavu, on the Congolese border with Rwanda. “He was 75, he had health issues. He explained that his wife Jane was worried and had been told not to go by his friend Al Alvarez, the poet. I was impressed he was willing to travel to Bukavu at all.” She fixed the trip, enlisting a veteran aid worker as their guide. “We weren’t long on the road before David and I had a kind of flirty relationship but there was no sexual element to it,” says Wrong. She also says he was “the most exquisitely polite man I’d ever met. It’s the first time I’d ever had a travelling companion carry my bags or open doors.”

When a former mistress of his, Suleika Dawson, published a memoir after his death – The Secret Heart – Wrong recognised the man she knew in its pages. She adds: “I was surprised by how many affairs there were but it didn’t surprise me at all that he had needed these female muses – for his creativity and self-confidence. It was very clear to me that he adored Jane. He talked about her all the time.”

As for le Carré the writer, Wrong found him “quite thin-skinned. He said: ‘I’ve reached the stage of my career where everyone’s out to tear you off your pedestal.’”

Despite her role in the making of the book, Wrong doesn’t rate The Mission Song among le Carré’s best. “David had spent so much time in communist Europe that the mannerisms, moods and foibles of its intelligence services and citizens came to him effortlessly. He had not had time to develop those instincts in Africa”.

But le Carré and Wrong stayed in touch. He invited her to glamorous parties, gave her a blurb quote for one of her books and generously offered her a substantial interest-free loan to support her writing. As the exhibition suggests, Wrong and le Carré’s other “secret sharers” seem to look back fondly on time spent with him in the shadows of his writing life, the crepuscular world that is so much a part of his mystique.

When Cornwell talent-spotted Varese, the younger man had abandoned plans to study the post-Soviet economy; it had fallen into the hands of gangsters, so it made sense to study them instead, he tells me on the phone from Yerevan. Did Cornwell (secret agent, retired) make Varese any other offer at that lunch in Oxford 30 years ago? With a CV such as his, surely the researcher was perfect material for the spying racket? “In our circles, the answer is always going to be no,” Varese says. “But you never know if that’s true or not.”

John le Carré: Tradecraft is at the Weston Library, Oxford, from 1 October-6 April 2026. An accompanying book, Tradecraft: Writers on John le Carré, edited by Federico Varese, is published by the Bodleian Library (£30). Order a copy from observershop.co.uk

Photographs by David Montgomery/Getty Images, courtesy of the Bodleian Library