“Mrs Shemirani, I’m going to have to stop you.” Those words, spoken by the coroner at a court in Kent, have become the soundtrack to my summer. They have been repeated many times at the inquest establishing the circumstances of 23-year-old Paloma Shemirani’s death. “Mrs Shemirani” is Paloma’s mother, Kate, a British anti-vaccine influencer with a sizable following on social media.

Paloma died in July last year after being diagnosed with a blood cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma. She had been told that conventional medical treatment would give her a high chance of survival, but she rejected chemotherapy in favour of alternative methods.

The evidence at the inquest was completed this week and the coroner’s conclusion – on how and why Paloma died – is expected on 2 October. Depending on the verdict, the coroner could, for example, issue a Prevention of Future Deaths report, advocating for measures to stop a death like this happening again. She could even refer individuals for criminal proceedings.

Paloma Shemirani was given an 80% chance of survival by doctors if she underwent chemotherapy

Inquests are often an opportunity for people to find answers to questions they might have about how a loved one died. In breaks, I watched other families at the court in Kent comfort one another as they prepared to hear evidence. This inquest, though, was a very different experience. Paloma’s family members, who represented themselves, questioned each other in court. Paloma’s twin, Gabriel, holds his mother’s beliefs responsible for the tragedy. By video link, Kate Shemirani has repeatedly claimed, without evidence, that NHS staff – including paramedics – were to blame for her daughter’s death.

The atmosphere has been tense, hostile and uncomfortable. I have seen medics questioned by people who believe conspiracy theories, and witnessed family feuds play out in real time. Frequently, the coroner has reminded those involved to conduct themselves according to the rules of the court.

~

This story began for me almost exactly a year ago, when I received an email I could hardly believe. As an investigative reporter for the BBC specialising in social media and disinformation, I am sent a lot of unusual emails, but this one stopped me in my tracks. It was from Gabriel Shemirani, then a 23-year-old student. He told me his twin sister, Paloma, had died weeks earlier after rejecting chemotherapy; he and his elder brother, Sebastian, wanted to tell her story.

Sebastian and I had been in touch before. It was around the time I first became aware of his mother – then a nurse, who has since been struck off – in the early days of the pandemic, when the anti-lockdown movement started gaining traction and holding rallies.

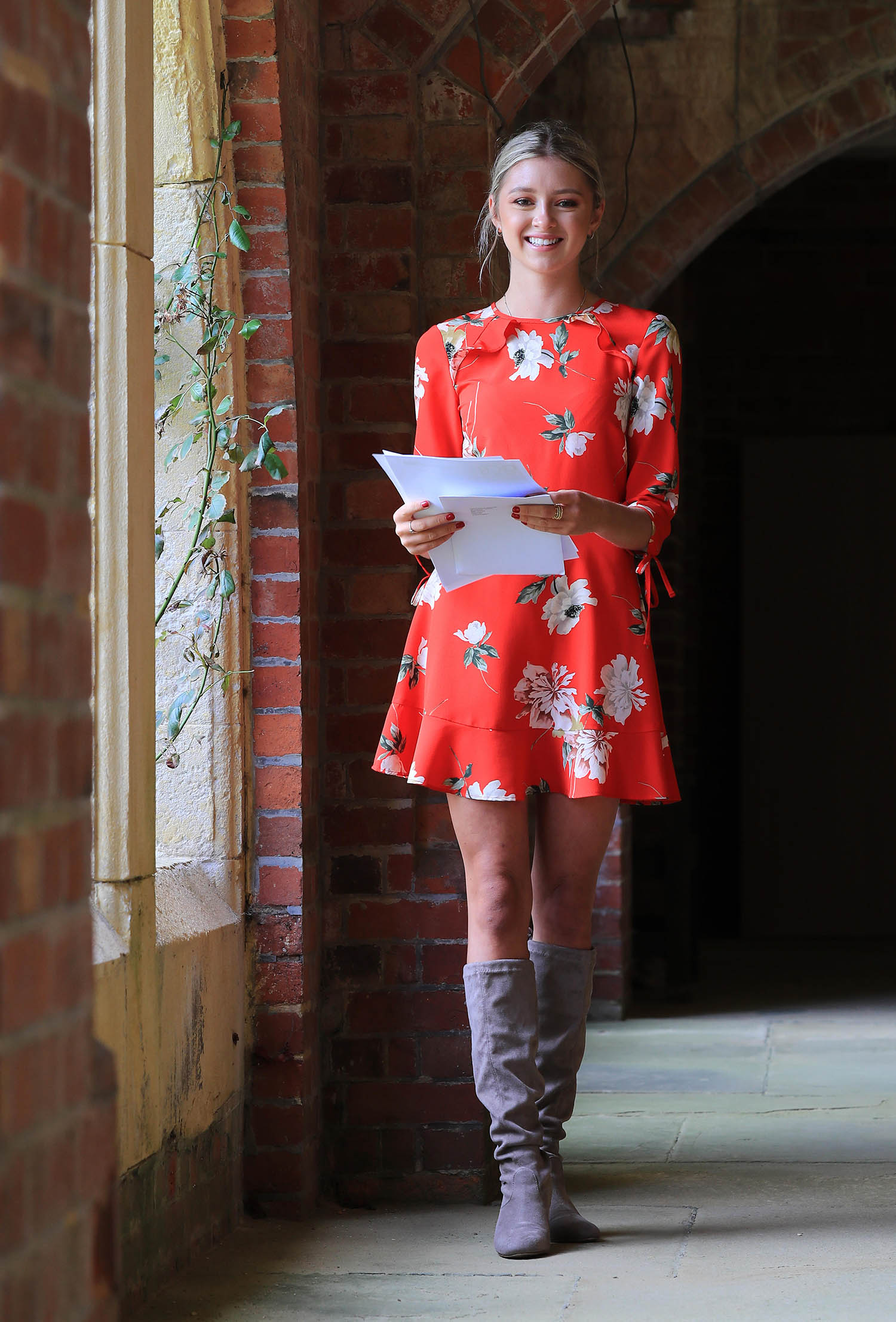

With her long blond hair and glamorous outfits, Kate Shemirani had quickly become one of the most visible conspiracy influencers in the UK. The comments she made online were far more extreme than questioning the proportionality of initial restrictions or, later, the safety of vaccines. She claimed the virus was a hoax, that vaccines were part of a sinister plot to kill millions – and that doctors and nurses should be punished for their part in it.

After Gabriel told me about Paloma’s death, I began a months-long investigation that exposed the real-world consequences of those anti-medicine conspiracy theories. I know how misinformation can inspire violence and tear apart families. In extreme cases such as Paloma’s, it can perhaps contribute to people losing their lives. Her story reflects the wider mainstreaming of anti-medicine ideas on social media and in politics. Since the pandemic, wellness ideas have fused with anti-establishment trolling – and now this toxic concoction of mistruths is racking up millions of views.

Kate Shemirani addresses crowds at a Unite for Freedom rally in London against lockdowns and mandatory vaccines in 2020

A year on, Gabriel hopes his twin’s story – and the inquest – can change things. “I want to get justice for my sister and I want to hold my mum to account,” he told me. “I want to stop this from happening again. What kind of brother would I be if I didn’t sound the alarm?”

My initial conversations with Gabriel unfolded over many months. They invariably came back to his childhood in the small town of Uckfield in East Sussex.

As a young boy, he played games with his siblings – Sebastian, Paloma and a younger sister, who does not want to be named – that had a “conspiratorial tint”. The family had 12 cats. “I established a religion around them [the cats] called the mugga religion,” said Gabriel. “My other three siblings were the anti-muggas and I was the persecuted ethnic group.”He collected the fur of one cat, keeping it as a secret treasure.

Conspiracy theories were part of the everyday of the home. The family would listen to the conspiracist radio host Alex Jones on the school run, as he described how US school shootings were staged, or how 9/11 was an inside job. The latter conspiracy theory was one favoured by Faramarz Shemirani, who moved to the UK from Iran in the 1980s; in Gabriel’s view, his father was the one who first drew their mother into this way of thinking. As children, Gabriel said, he and Sebastian were convinced that the royal family were shape-shifting lizards.

As kids, he suggested, he and his twin were peas in a pod. Paloma was funny, would steal his slices of pizza, put on comic voices and would get into all the games, including the cat religion. He said, however, their mum would increasingly control what they could or could not eat, and he and his siblings were left terrified of ever getting ill – let alone cancer.

Things changed, he said, with his mother’s breast cancer diagnosis in 2012. Shemirani had the tumour removed via surgery, but credited alternative therapies with her recovery. By 2016, Gabriel’s parents had split up and Shemirani started to share her experiences online, building a following by promoting health misinformation. During the pandemic, she found a bigger audience, pushing conspiracy theories about vaccines and Covid.

Once they were old enough to think for themselves, Gabriel and Sebastian rejected Shemirani’s beliefs. After they left home for university, both brothers became estranged from their mother (Gabriel even stopped calling her “Mum”). But Gabriel said his twin sister’s approach was different: she wanted to get along with her mum. A close friend of Paloma’s told me Paloma had accepted her mother’s claims that her breast cancer had been treated with alternative medicine and shared her mother’s belief that wearing sunscreen could cause cancer.

Paloma tried to stay in touch with her mother once she left home to study Spanish and Portuguese at Cambridge University. All the friends and family I’ve spoken to describe her as incredibly bright and a lover of literature. She organised a fashion show, excelled in her degree and made lots of friends. She had hoped she might one day become a professor.

But while she was back home during the university holidays – as messages I have seen suggest – her relationship with Shemirani was troubled. In one incident, Paloma described being “abused” by her mother and said how “hurt” she made her feel. At times, Paloma cut off contact with her mum entirely. Gabriel – and several of Paloma’s friends – told me she had begun to move away from her mother’s beliefs: she would eat some meat or use toothpaste with fluoride. But, like her mother, she remained sceptical about the Covid vaccine and refused to have it.

Doctors said she had an 80% chance of recovery with treatment

Doctors said she had an 80% chance of recovery with treatment

In late 2023, not long after graduating, Paloma was living independently in a flatshare in Kent. She began to have chest pains and breathing difficulties. Doctors suspected a tumour. Gabriel showed me texts he received from his sister in December of that year, as she awaited test results: “Idk [I don’t know] it’s just crap that I felt like everything was going well for me,” she wrote. “Like I got away from Kay [her mother’s birth name] I finally got my freedom with a new flat … I got a job… I don’t remember the last time I felt stressed about work now I’m not at Cambridge. Like it was all on the up.”

On 22 December 2023, Paloma visited Maidstone hospital, where doctors diagnosed her with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Untreated, this type of cancer can be fatal, but doctors told Paloma she had an 80% chance of recovery if she underwent chemotherapy.

This period has been scrutinised intensely at the inquest. A range of NHS medics who were involved in Paloma’s diagnosis were called to give evidence, as were the alternative practitioners she was in contact with.

Paloma told her mother the news. Gabriel and Paloma’s then boyfriend Ander Harris told me Paloma wanted her mum’s support, even though their relationship had recently been strained. Shemirani told the inquest that when her daughter shared her diagnosis, they had not spoken in about six weeks, but insisted their relationship was still positive. She also denied any allegations of abuse.

Shemirani said she would come to the hospital to be with her. Gabriel said Paloma was worried about seeing her mother and spoke to medical staff about her concerns. Shemirani sent a message to Paloma’s boyfriend, saying: “TELL PALOMA NOT TO SIGN [OR] VERBALLY CONSENT TO CHEMO OR ANY TREATMENT.”

~

Messages from the time also show Paloma contacted others for advice about what to do next, including an alternative therapist who was a former partner of Shemirani called Patrick Vickers. He has been mentioned during the inquest but the coroner said the court had received no response to its efforts to contact him.

When Paloma asked him in a text about the “80% chance of cure” the doctors had said chemotherapy would offer, Vickers said that was “exaggerated”. He encouraged Paloma to start something called the Gerson therapy and to maybe consider chemotherapy if her symptoms did not improve after six weeks. Gerson therapy involves a strict plant-based diet, along with juices, supplements and coffee enemas. Some people claim – without scientific evidence – it can be used to treat a range of cancers. When I contacted him, Vickers said any “assertions that I played a role in her [Paloma’s] death are legally inaccurate”. He was not Paloma’s Gerson practitioner.

Dr Arunodaya Mohan, the consultant haemotologist at Maidstone hospital who diagnosed Paloma’s cancer, was asked during the inquest whether she was confident that Paloma had the capacity to make own decisions: Mohan said she was. She also said that Paloma had initially seemed open to exploring all possible treatment options, including chemotherapy, and that medical staff at the hospital had discussed safeguarding concerns regarding Paloma’s case.

Paloma Shemirani was a ‘clever, funny’ student at Cambridge who had hopes of becoming a professor

At the inquest, various people described how clever Paloma was. But Gabriel told me just how terrified her illness made her feel, and about her fears of infertility and hair loss as treatment side-effects.

Gabriel remembered learning that Paloma had decided not to pursue chemotherapy – at least for the time being – and would try alternative methods such as the unproven Gerson therapy. He was devastated. He was especially concerned that Paloma had decided to move back home with their mother. A voice note played in court heard Shemirani describe her plans for Paloma’s care to a former boyfriend.

“Imagine that she’s hanging on a cliff with her fingernails and there’s no safety net at the bottom. And if she falls, that’s it ... This is one Christmas that she’s gonna have to do as asked, really,” Shemirani explained. She also spoke about having “lots of other doctors on board”. In the early hours of Christmas morning, Gabriel went to his mother’s house to try to persuade Paloma to leave. Paloma was asleep, and Gabriel argued with Shemirani. Paloma described to friends how distressing the incident was at the time; her mother said the same in her testimony at the inquest. Gabriel told me he was desperate. That was the last time he saw his sister alive.

Paloma became increasingly isolated, cutting people off. Gabriel said he once asked her to meet up with their sister. “[Paloma] responded: ‘Oh, I can’t be out because of the bad air.’ Kate had convinced her that the air was bad for her.”

~

When I spoke to Gabriel’s brother, Sebastian, in 2020 about the impact of the misinformation his mother was sharing about Covid, he expressed concerns that something terrible would eventually happen. “When [the pandemic] is over in three or four years time, and everything she said is forgotten, and the global genocide hasn’t happened – people will forget about it. But the disaster that goes on within my family ... That stuff stays for ever.”

A few months after I first spoke to Sebastian, I was surprised when Shemirani agreed to answer my questions about an anti-vaccine video. She invited me to her home and defended her views about the vaccine. She offered me juice and fruit, introduced me to her many cats and we walked her dogs.

The house was incredibly tidy. The walls were adorned with photos of her four children as kids, smiling. The images felt at odds with the picture both Sebastian and later Gabriel painted of their childhood; this is the house where they grew up – and the house in which Paloma would collapse, before dying in hospital.

Around the time I met Shemirani at her house, some of her social media accounts were suspended by the big platforms. In 2021, a Nursing and Midwifery Council panel determined Shemirani (who was not then working as a nurse) should be struck off for promoting misinformation about the pandemic.

In 2022, however, some social media platforms, including Elon Musk’s rebranded Twitter service X, changed their rules, opening up new opportunities for Shemirani and others. On X, she continued to describe herself as a nurse and – on her website – to offer advice to patients for money. She also shares unproven therapies and other cancer misinformation on X. In the past six months, she has reached more than 4.5m views across the big platforms.

“Do I think the people who are spreading radical misinformation should be banned?” Gabriel said. “Yes, wholeheartedly. For anyone that says: ‘Oh, but they have a right to free speech’ – science isn’t something where anyone can say what they want and they don’t have to back it up with any evidence.”

According to Gabriel, the reactivation of his mother’s account motivated her to recommit to her alternative health ideas, no matter the cost. Shemirani did not post much about Paloma’s diagnosis online until after she died. But Paloma did share an Instagram post announcing her own alternative health journey. Under photographs from the months after her diagnosis, Paloma wrote: “I’ve made it to May with the incredible help of my Gerson practitioner, and the loving support of my wonderful mum, sister and utterly devoted friends. These months have been unimaginably tough, but it has been an amazing time learning about health, faith, friendships and much more. I can’t wait to share with you more steps on my road to recovery.”

~

By this point, Gabriel had been blocked by his twin sister on social media. But while Paloma remained adamant that she was happy with her decision not to have chemotherapy, her online post seemed at odds with what some of her friends were observing. They told me how Paloma became more and more unwell. She told them about a new lump in her armpit, which Shemirani told her was a sign the cancer was leaving her body.

Gabriel reported what was happening to Paloma to social services and was left frustrated by what he saw as slow progress. In April 2024, he decided to take legal action in an effort to save his sister. He wasn’t arguing that Paloma did not have capacity, but he wanted an assessment of the appropriate medical treatment. The court case took up “months” of his life, he told me. When Gabriel’s parents questioned him as “an interested person” during the inquest, a lot of their discussion focused on that court case; they even questioned his own capacity. When the coroner tried to stop mentions of Gabriel’s medical history, Gabriel said he was happy to answer, attributing any difficulties he had with his mental health to his time growing up “with you two”.

Gabriel’s 2024 court case was overtaken by events. It ended that July, when Paloma suffered a heart attack caused by her tumour. She was taken to hospital, but after several days, her life support was switched off.

~

Some of the most striking moments at the inquest have come from testimony about Paloma’s final days. (Gabriel, who had not heard many of these remarks before, said they, tragically, almost made her feel “alive again”.) An osteopath who saw Paloma for the first time on the morning of the day she collapsed described how unwell she was by that point. In emails read to the court, Paloma described having difficulty swallowing and trouble carrying out some of the alternative therapies.

The court was played a 999 call, made by a friend of the family, who arrived at the house shortly after she collapsed. It was deeply upsetting to hear. It also contradicted Shemirani’s version of events that paramedics were responsible for Paloma’s death – an assertion she has repeated in court, online and in podcasts.

Shemirani told her a new lump in her armpit was a sign the cancer was leaving her body

Shemirani told her a new lump in her armpit was a sign the cancer was leaving her body

Shemirani can be heard saying “she’s dying”, before paramedics arrived. She was giving Paloma CPR before paramedics took over when they arrived. They also administered adrenaline, in keeping with UK guidance. The paramedics who gave evidence accused Shemirani of “presenting a challenge” as they tried to save Paloma’s life in her family home. The court also heard from intensive care doctor Peter Anderson, who was involved in Paloma’s care at the Royal Sussex County hospital in Brighton after her collapse. He told the court that Paloma had a large cancerous tumour blocking her airways that likely triggered the heart attack. He also said it was very likely that she had suffered irreversible brain damage as a result. A few days after he first saw Paloma, the decision was made to take her off life support.

~

While his twin sister was lying unconscious in intensive care, Gabriel was not informed of her condition, or the decision to remove her life support. He found out days after she had died – from his lawyers, not his parents. He had to tell his brother himself. He told me the experience was as painful as being “burnt alive”.

When I first contacted Shemirani after her daughter’s death, she seemed open to an interview. She started her message with: “I trust you are well, considering how many Covid shots that you likely were deceived into taking.” But then she decided against talking and instead sent letters to me, also signed by Paloma’s father, Faramarz. They told me they have evidence that “substantiates that Paloma died as a direct result of medical interventions given without confirmed diagnosis or lawful consent”. I have not seen any evidence to support these claims.

In the letter, they accused me and the BBC of promoting the Covid vaccine, which they said has been “linked by leading scientists, legal experts, and whistleblowers to a biological weapon programme”. They said any attempt to “misrepresent or distort” Paloma’s death “will be treated as evidence of [the BBC’s] continuing institutional alignment with pharmaceutical narratives”.

Since parts of my investigation have been published, I have been inundated with patients, relatives, doctors and nurses warning about the spread of ideas promoted by Shemirani. The more social media algorithms promote unfounded anti-medicine ideas, the more visible they become, and the more politicians and other influencers feel emboldened to push these same ideas.

Gabriel hopes the inquest can catalyse change. He wants a new proposed law to be introduced that stops people misusing the title “nurse”. He would also like politicians to rethink what is considered harmful content online in the Online Safety Act. He wants safeguarding training for social workers and medical staff with patients whose relatives are expressing conspiracy theories. And he wants the Cancer Act of 1939 – which prohibits false advertising of cancer cures – to be urgently updated to better reflect this new social media environment.

When Gabriel speaks to me about his twin, his face softens. He misses Paloma. After the daily noise of the inquest, he grieves for her in the quiet hours of the night. Her name in Spanish can mean both dove and pigeon, which he tells me is apt.Paloma was beautiful and goofy and clever and funny. The inquest has been the first time he has accepted her death: “I realise I now have the duty to live as a pair,” he said. “There is a life still out there to be lived that my sister was not able to live. It is my responsibility to live that life that she lost.”

Listen to Marianna in Conspiracyland 2 on BBC Sounds. Panorama – Cancer Conspiracy Theories: Why Did Our Sister Die? is available on BBC iPlayer

Photographs by Tori Ferenc/Alamy

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy