In the mid-1970s, the music press keenly aligned itself to rock. And it seemed to be in denial of another art form – a particularly working-class one that didn’t involve watching performers, but instead made the punters themselves the stars: club culture. As punk turned into post-punk, there was no mention of the burgeoning soul-boy/soul-girl scene that drew in kids from all over the country to show off their natty styles and balletic skills on the dance floor. With looks fashioned from plastic sandals, Smith’s work trousers and mohair sweaters, their backbeat was 12-inch disco and spun-out jazz funk.

Bryan Ferry, who Peter York had called “an art object that should be hung in the Tate”, was a crossover inspiration. Despite punk, he was still relevant and, for a while, clubgoers would emulate him, tucking their ties into khaki GI shirts and growing their hair into heavy asymmetrical wedges. With its bassline hook, Love is the Drug by Roxy Music, the band Ferry fronted, went on to inspire Chic and dance grooves to come.

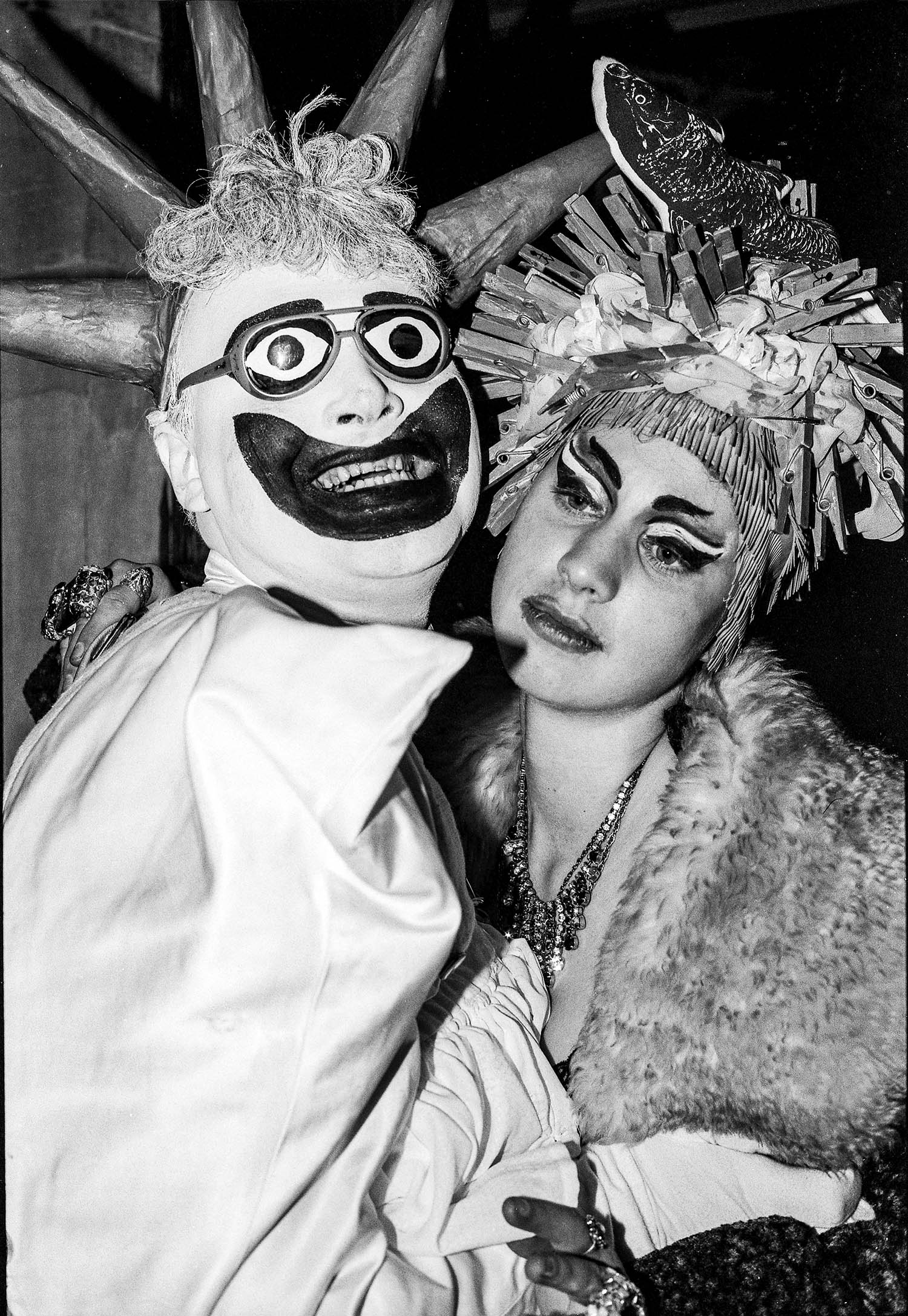

Performance artist Leigh Bowery, left, and friend. © David Koppel

But the overseeing prophet who would bring together the disparate youth cults of the dance floor and the auditorium, creating a scene that would eventually bloom into the cultural zeitgeist of the 1980s, was David Bowie.

Bowie had tutored us in so many ways. We were the generation who’d first had its head turned by the androgyny of Ziggy Stardust; who’d had its love of soul validated by his Young Americans album, and then been introduced to the art of Heckel and Kokoschka, and the motorik electronica of Berlin, with all that city’s tantalising history of decadent Weimar-era cabaret.

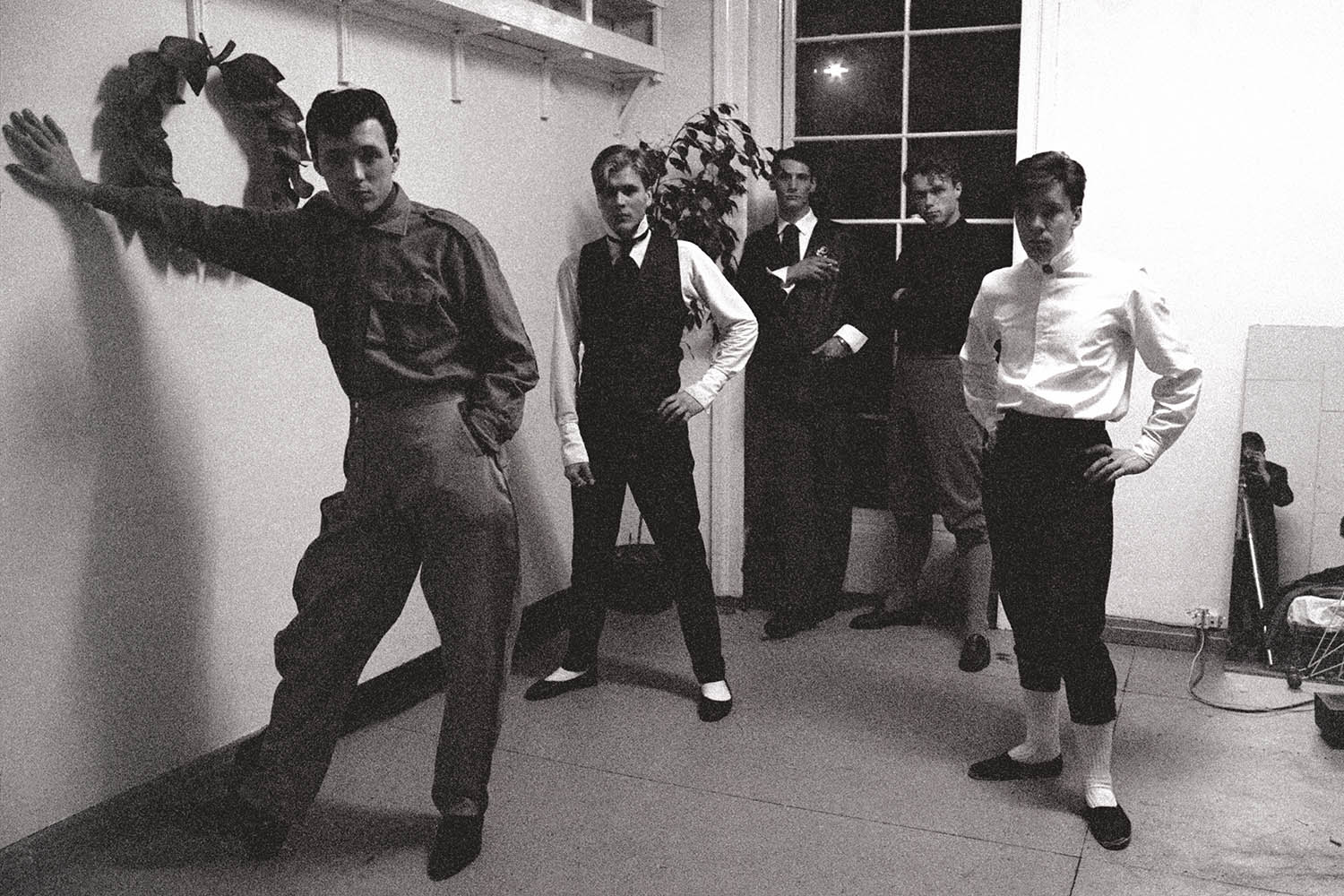

Spandau Ballet, including Gary Kemp, second from right, played their debut gig at the Blitz

It was our love of Bowie that brought fashion students, post-punks and ex-soul boys and girls together in 1978, when a 19-year-old Welsh lad called Steve Strange started his Bowie Night every Tuesday at a small basement dive in London’s Soho called Billy’s. The DJ, and Strange’s creative partner, was a red-headed cockney named Rusty Egan. He’d once played drums for Glen Matlock’s Rich Kids, but now, in a vintage demob suit and with LOVE and HATE tattooed on his fists, he’d returned from Berlin with a heap of electronic dance records. Egan was determined to raise the profile of the DJ and deliver to the dance floor a different kind of playlist.

“Jump Aboard the Night Train”, the flyer teased. £2. But to get on that train, one had to impress Strange at the door. He wanted like-minded visitors to partake in his vision of a club. Given that my first impression of himwas of a Cossack with a quiff, it was a high bar. But in my soul-boy finery – and, more to the point, with a brother blessed with Hollywood looks – we boarded.

George Michael and the Blitz’s ‘hat-check girl’ Boy George at the Limelight. © David Koppel

As we nervously took the stairs down, a slow pulsing synth emanated from below: Kraftwerk had replaced the frantic tempos of disco and punk. There, in the tiny dance space, two boys dressed in sashes and Chinese slippers, eyeliner and diamante, were holding hands and performing a never-before-seen slow-motion jive. I was mesmerised.

The space buzzed with artful kids in their late teens, dressed mostly in homemade exotica and charity-shop finds that seemed both nostalgic and futuristic. It was a theatre of youth. This was an open mix of straight and gay, but with an equality of flamboyance. In the streets above, the clubgoers might have seemed provocative misfits, but here, to me, they were magnificent.

Singer Marilyn was a Blitz club regular

To the young writer Robert Elms, I must have looked overwhelmed but familiar: our musical journey to this spot was identical. One night at Billy’s, he appeared in front of me dressed like comic-book hero Dan Dare, in a sky-blue buttonless top with a silver sash across his chest; his hair a red wedge over one eye. We would spend nights together discussing the potential of the people in the room and the cultural relevance of it all. Postwar youth culture had evolved in a series of dialectics and our coming-of-age had left us with the baton. We were determined to charge across the line and into the 80s.

After a short while, Strange and Egan were evicted from Billy’s and our Tuesday nights moved down the road to a large wine bar called Blitz. Here the future Boy George was the hat-check girl; Sade, a fashion student, was a regular. We started to attract a certain infamy from the media. Who did we think we were? And could we take your picture before you go in? It was here that my brother Martin, three friends and I formed what became the Blitz house band, calling ourselves Spandau Ballet at Elms’s suggestion. The ambition of the kids inside to play a part in the future of fashion, film, choreography and music was tangible. This was tomorrow calling.

Actor and singer Patsy Kensit and designer Jasper Conran at the Limelight club in 1987. © David Koppel

Gradually, copycat clubs started to pop up in town, and we’d even heard about similar venues in Birmingham, Sheffield and Cardiff’s Tiger Bay. The music press was seething but couldn’t resist it. The big magazines were on the run and Nick Logan’s The Face, with its freshly enlisted Elms, was about to make them all look like a thing of the past.

Suddenly, everyone wanted to be seen and in a club. As the 80s arrived and some of us entered the pop charts, Strange and Egan moved into the multi-storied Camden Palace, attracting the Smash Hits crowd and a new commercialisation of club culture. Later, the Canadian Peter Gatien, hungry to be at the centre of western pop culture, opened the Limelight in a disused Welsh Presbyterian Church on Shaftesbury Avenue. The music press couldn’t get enough of the club. Photographers were embedded in order to get pics of pissed popstars falling out of toilets; writers were sent to the frontline for faux pas and gossip. The Limelight was the new gig. But while the Smash Hits crowd had taken to the dance floors in large numbers, the Blitz Kids found themselves caught behind a velvet rope, caged into the oppressive heat of an ivoried top bar, to be admired and pilloried, left to pass the baton to rave and the cult of the DJ.

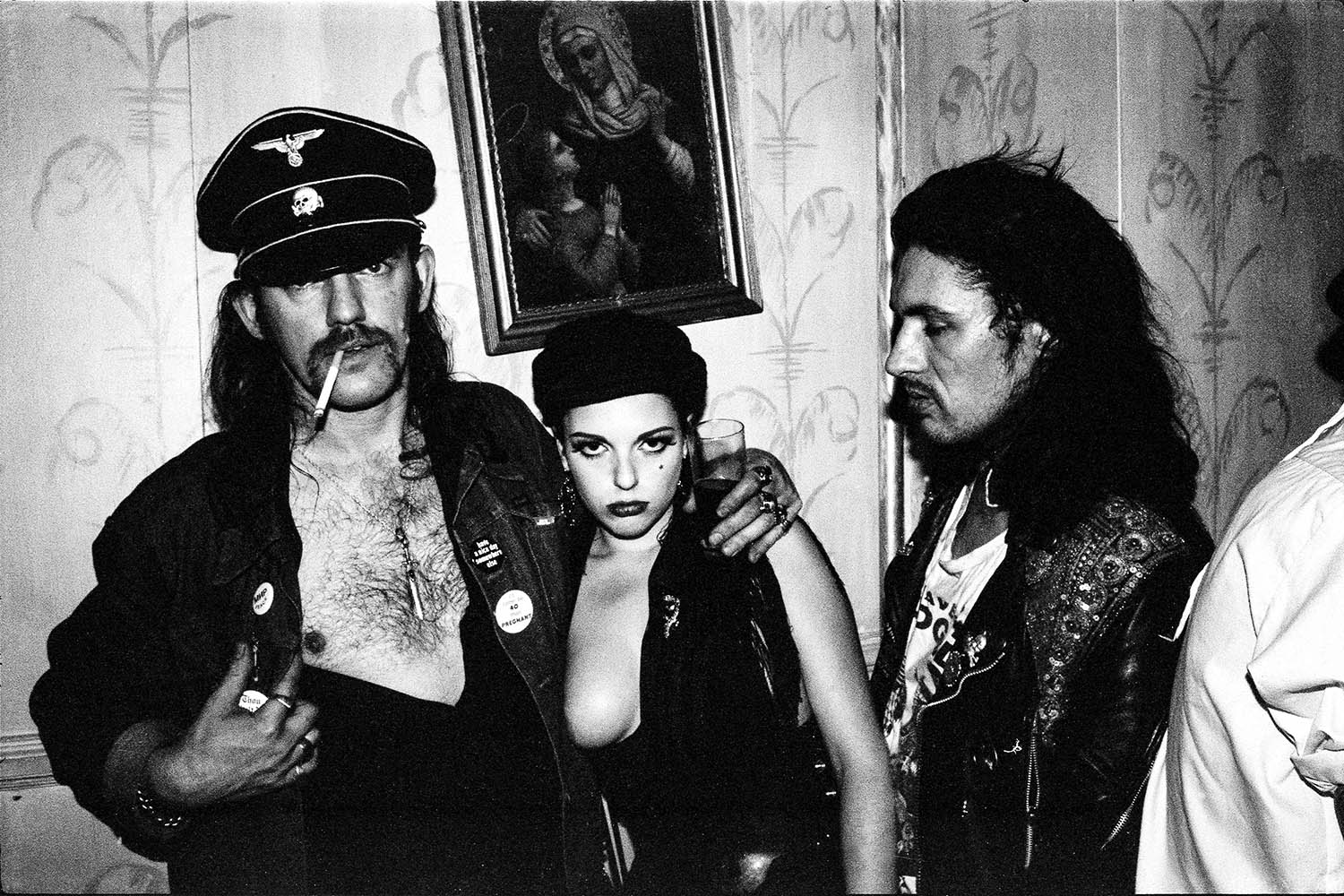

Motörhead’s Lemmy and his girlfriend at the Limelight, with Mark Manning of the band Zodiac Mindwarp and the Love Reaction. © David Koppel

To many, those Tuesday nights at Blitz, with Strange and Egan’s curation, were proof that clubs could be a place where young people could challenge the status quo and leap into the future, not just pose and dance. Although that too has always been important.

Spandau Ballet’s Everything Is Now: Vol 1 – The Early Years 1978-1982 will be released by Parlophone on 10 October

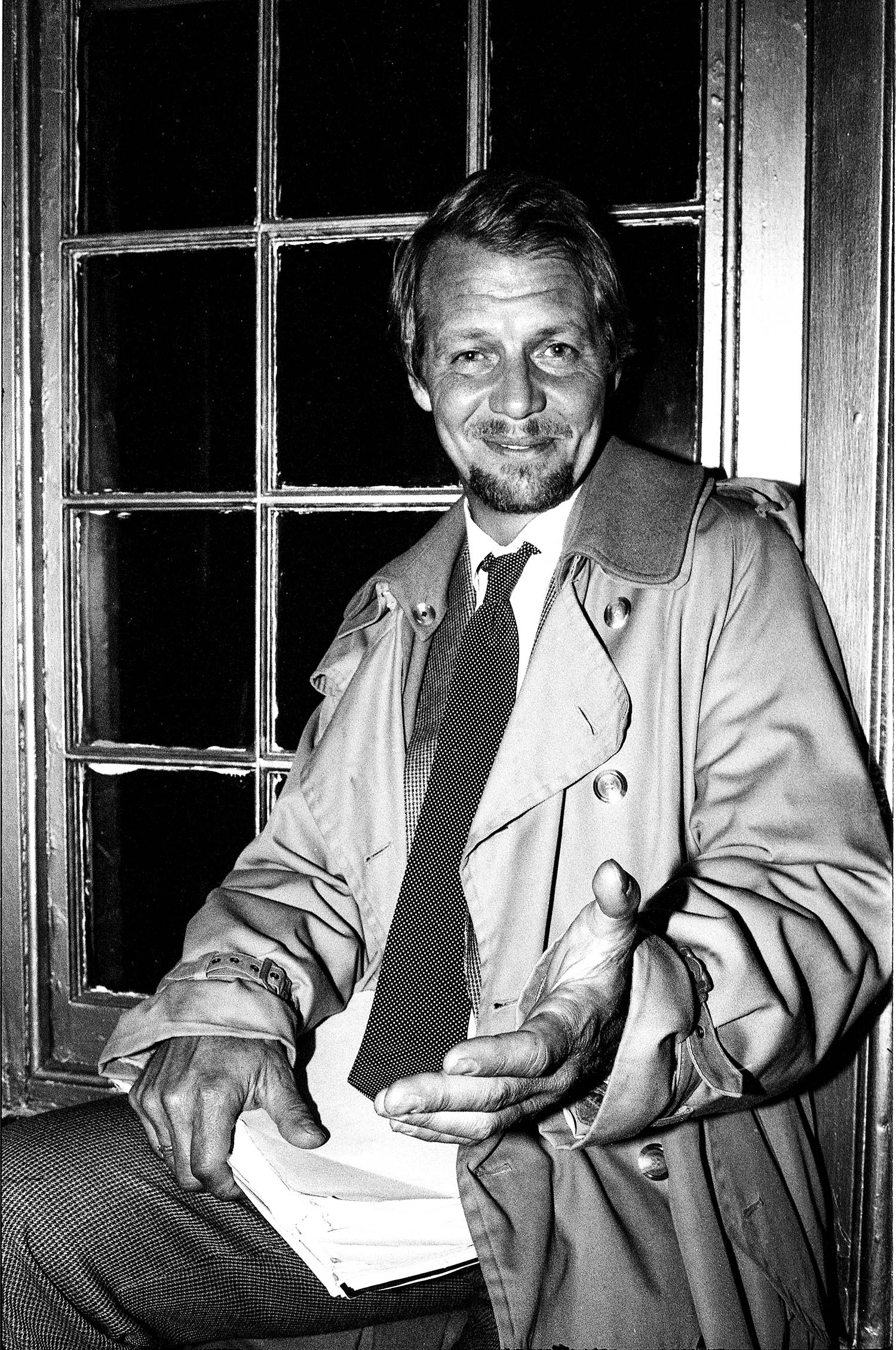

Actor and singer David Soul eschewed the dress code. © David Koppel

Odes to clubland

Blitz: The Club that Shaped the 80s is at the Design Museum, London W8, from 20 September

Blitz: The Club that Created the Eighties by Robert Elms is published by Faber & Faber on 25 September

David Koppel’s photography book Limelight is available from davidkoppel.co.uk. An accompanying exhibition is at Zebra One Gallery, London NW3, from 9 October

Photographs by David Koppel, Robert Rosen