Related articles:

Photographs Mats Engfors

When he was young and still regarded gravity as a negotiable concept, Will Beilharz climbed 80m up a redwood in northern California, slung a hammock between two tree limbs, and spent the night suspended in a fog of redwood pine needles and youthful bravado. Provisions were modest – granola bars, paperbacks, a flashlight – but the epiphany was enduring. “It made me see how powerful it is to connect with nature so directly,” he says. “To put your trust in a tree for shelter, the way humans once did long before we ever built houses.”

The idea is less fanciful than it may seem. Our primate relatives have long favoured the canopy: chimpanzees fashion twig mattresses for safety and repose, young orangutans devote years to mastering treetop nest construction. Throughout human history people have chosen to live aloft among the branches. Pliny the Elder wrote in 77 CE of lavish Roman feasts hosted in plane trees; in the gardens of Renaissance Florence, Medici courtiers indulged in leafy debauchery; and Christian ascetics known as Dendrites once made their homes in trees, renouncing the world below.

Branch out: the Lift, in Ubud, Indonesia, was designed by Alexis Dornier to explore less invasive architecture

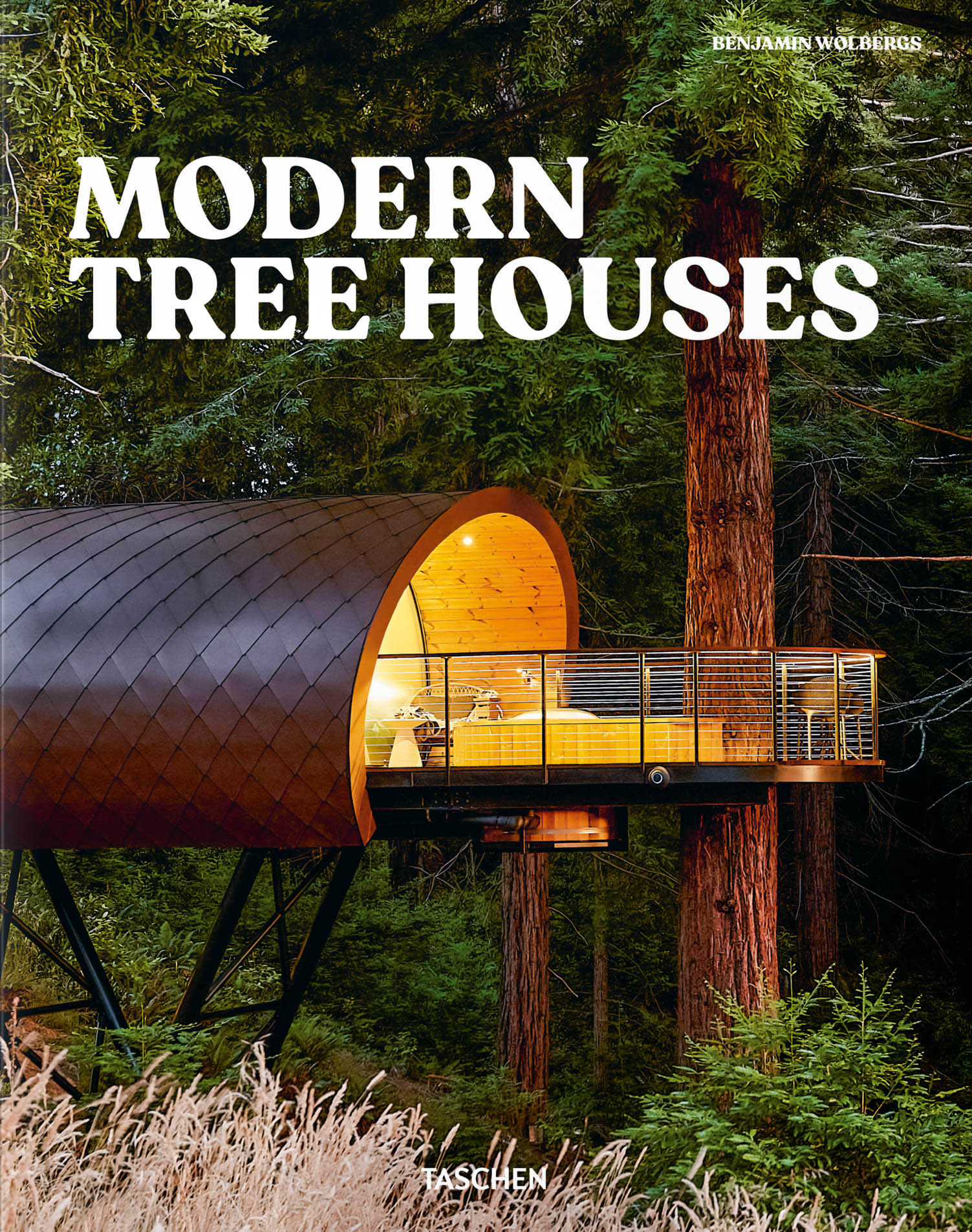

Today, Beilharz is one of a new generation of designers reintroducing architecture to the canopy. Recognising that not everyone shares his taste for vertiginous adventure, he founded a firm to build tree dwellings engineered for comfort and contemplation – from Yoki, a multilevel forest retreat in Texas, to Spyglass, a sleek tubular form wrapped around a redwood in Sonoma County, California. These aren’t rudimentary, playful tree houses as we might remember from childhood. They’re forward-looking experiments in how we might live more lightly, and more attuned to the world around us.

And Beilharz is not alone. Since the late 1990s, architects have been rediscovering this ancient, seemingly whimsical typology – not for whimsy’s sake, but for sustainability, intimacy and a renewed dialogue with nature. In Norway, Sally and Kjartan Aano built their hotel, Woodnest, after discovering a shared longing for life above ground. Their approach to design was as much emotional as it was technical, favouring quiet immersion over spectacle. Set above a fjord, their structures reflect an ethos of quiet withdrawal. For Sally Aano, the trees are more than scenic companions; they are interlocutors. “In nature, you ponder life’s big questions: Why am I here? What is my purpose?” she says. “You become more attuned to the environment, to the flowers, the animals, the ever-changing way of nature. It’s about returning to our roots.”

Similar convictions shaped Peter Bahouth’s Secluded Intown Tree House in Atlanta. Built around an old pine, the structure began as a personal side project and, to Bahouth’s surprise, became something of a pilgrimage site when he opened it to the public. Guests have proposed, honeymooned and healed here – one woman, grieving the death of her husband, described it as the first place she could finally exhale. “You’re not plugged into everything else when you’re sleeping in the trees,” says Bahouth.

Cosy retreat: Woodnest in Norway, designed by Helen & Hard, offers views over the fjord

Tree houses, by their very nature, resist standardisation. There is no universal floor plan, no cookie-cutter chassis, because they are shaped by the trees they depend on. Some go a step further and resemble trees themselves: Like Bert, made possible by the engineering sorcery of cross-laminated timber. Dreamed up by architects Fei and Chris Precht, the pod-like structure sprouts from the forest floor like a cartoon sapling. “The greatest feeling of freedom for a grownup is to be like a child again, even if it’s only for a moment,” says Fei Precht. Bert doesn’t just sit in the forest – it plays along. “When you walk into a forest, you’re no longer the centre of the universe, but only a small part of a much greater sequence of events.”

Today, few tree houses are actually perched in trees, most are more diplomatically adjacent. The reason most modern tree houses aren’t actually attached to trees has less to do with romance than with regulations. Structural concerns, building codes and legal ambiguity all conspire to keep architects at arm’s length from the branches. In much of the world, tree houses exist in a kind of bureaucratic grey area: too ephemeral to qualify as real estate, too ambitious to be dismissed as playthings. With no clear planning guidelines, both builders and local authorities are often left to improvise. The safest bet is to avoid puncturing the tree altogether – most tree houses today rest on poles, which support the structure’s weight and sidestep the biological risks of drilling into living wood.

Related articles:

Take the Kusu Kusu Tree House, delicately inserted into a 300-year-old camphor tree by architects Takashi Kobayashi and Hiroshi Nakamura. Rather than piercing the trunk, they devised a framework to embrace it. The architects employed a series of minimally invasive construction techniques to preserve the tree’s integrity. “For the foundation, we placed pillars between the roots, to avoid using concrete and extensive excavations,” Nakamura explains. “We used the tree’s structure as scaffolding and constructed the tree house by navigating around the branches, similar to how birds build their nests.”

Floating on air: the 7th Room in Norway blurs the boundaries between indoors and out

Not all trees are created equal when it comes to bearing guests. Their vulnerability depends on whether key nutrients and water travel through the heartwood – the central, often dead core – or the outer sapwood. The latter is more sensitive, more reactive, more easily bruised. For tree-house architects, that means working with a kind of botanical bedside manner. At Woodnest, for instance, the architects designed a custom steel collar that cinches the trunk without cutting into it.

It may not always be the search for Eden that beckons us into the canopy, perhaps it’s something simpler: a longing for perspective, for distance, for a more elemental connection. Researchers across disciplines have long tried to explain our affinity for trees. The conclusions are familiar yet resonant: trees are a mood booster that offer us peace and quiet, reduce our stress and anxiety, and supply us with fresh, clean air. Sometimes, all it takes is one deep breath in the woods to remember you’re part of nature and not just a visitor. Few tree houses capture this better than 7th Room by Norwegian architecture practice Snøhetta. The structure appears to levitate 10m above the ground, among the canopy of the boreal forest, and follows a U-shaped plan; in the central space, the designers stretched a net around a pine tree, creating a floating terrace where people can lounge mid-air and watch the northern lights.

In a tree house, we find ourselves at the threshold of the tangible. We hover in the air yet remain connected to the earth, close to the wilderness of the woodlands, but not too far from civilisation, which we can call upon for help if anything seems amiss. Researchers refer to this as “liminality,” a kind of domesticated form of wilderness. Henry David Thoreau, the American prophet of solitude and trees, believed that stepping into nature allowed us to approach something more essential – something truer than the world below. In his legendary book Walden, he wrote: “I went to the woods, because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life… and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived… I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life.” It was a call not for retreat, but for reckoning.

Hanging out: sanctuary via rope bridge at Peter Bahouth’s Secluded Intown Tree House in Atlanta

Japanese master builder Takashi Kobayashi shows just how poetic a labour of love can become when it takes root in a tree. After discovering a book by American master tree-house builder and author Pete Nelson – a pioneer of the modern tree-house movement – during a trip in the late 1980s, Kobayashi hoisted his first hideout in a Himalayan cedar above his vintage-clothing bar in Tokyo’s Harajuku district. It was less a design exercise than a declaration; a manifesto for a slower, more egalitarian way of life. “I didn’t want to just build a tree house,” he says. “I wanted the lifestyle it represents.” That ethos – imperfect, impermanent, gently defiant – shapes every structure he raises, always letting the tree lead.

You can feel it in his Kusu Kusu Tree House, whose bolt-free steel lattice embraces that truly ancient camphor without ever touching it. The project embraces what Kobayashi calls “looseness”: joints that flex, materials that weather, lifespans he cheerfully estimates at about 10 years. Long enough, he says, to remind us that buildings, like the branches that cradle them, are meant to sway, to live, and, eventually, to return to the forest.

So, what are modern tree houses? They are at once symbols of escape and agents of return – part childhood daydream, part ecological manifesto. They serve as weekend refuges, forest offices, bird hideaways, or Instagram-ready sanctuaries. Some are austere, others unapologetically indulgent, but all of them ask a version of the same question: What happens when we trade the excesses of modern comfort for something smaller, simpler, closer to the canopy? The answer, it seems, is not deprivation, but clarity. When we move lightly through the world, nature has a way of responding. It opens up. It lets us in.

At first, tree houses may seem like an improbable place to live in today’s world. Humans aren’t built for climbing, and elevated living complicates plumbing, wiring, and just about everything else. Yet the appeal endures. There’s something about rising above the ground – however slightly – that shifts our perspective, loosens our grip on routine, and makes room for reflection. Tree houses pare life down to its essentials and remind us how little we actually need to feel whole. In a world engineered for more and more, they quietly offer less – and, in doing so, suggest it might be enough.

This is an edited extract from Modern Tree Houses by Florian Siebeck, published by Taschen at £50 (taschen.com)

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy