It was always an uneven match – Unesco v football – played on the Liverpool waterfront. On one side, earnest officials striving to defend the integrity of the city’s historic docks. On the other, half the football-following public of Liverpool, frustrated by three failed attempts over 25 years to find a site for a new stadium for Everton FC.

They were hungry to get on with the latest plan to build it, which proposed filling in the 1848 Bramley-Moore dock, part of a grand sequence running along the Mersey towards the Irish Sea. That this was within a world heritage site called Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City was, for them, a secondary concern.

The former mayor of Liverpool, the Evertonian Joe Anderson (who is currently awaiting trial on charges of bribery and misconduct which he denies), once dismissed the designation as “a certificate on the wall”. The club went ahead with the plan, with Anderson’s blessing, on land owned by the giant Mancunian property company the Peel Group.

Unesco, its patience already tried by Peel’s plans to build Dubai-like skyscrapers, and the carbuncular development of the area around Liverpool’s Pier Head and its magnificent early 20th-century commercial buildings known as the Three Graces, removed the world heritage site status, for only the third time anywhere in the world. Central government might have been expected to get involved in an issue of such significance, but the relevant secretary of state at the time, Robert Jenrick, stayed out of it.

It is a convincing object of pride and pilgrimage that holds its own among structures past and present

It is a convincing object of pride and pilgrimage that holds its own among structures past and present

That was in 2021. Since, the dock has been filled with 480,000 cubic metres of sand. And last weekend, the outcome of this saga, the 52,769-seat £800m Hill Dickinson Stadium, welcomed its first capacity crowd to a friendly match against AS Roma. Blues fans, who started trooping towards the ground more than four hours before kick-off, were mostly delighted. The game itself, a 1-0 defeat, didn’t much matter.

The design of the new building aims to combine the glossy corporate money mills of modern stadiums with the steely resonance of its former home, the 133-year-old Goodison Park, which will now be the ground of Everton Women. The new stadium, sponsored by an international commercial legal firm, contains 17 restaurants and lounges, and boasts the first “loge seats” in Europe, broad upholstered items available at premium prices, each with its own video screen and drinks holder.

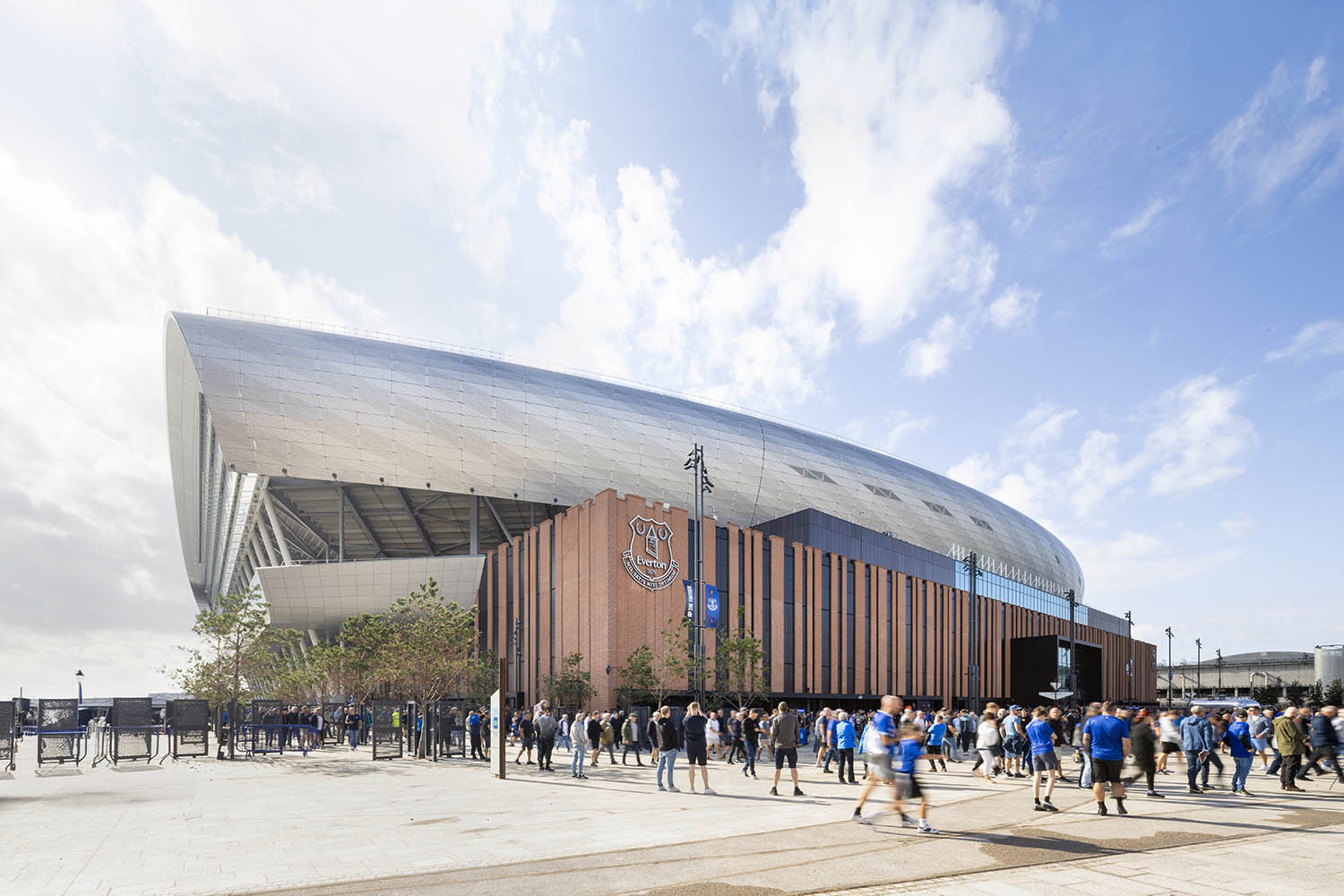

Goodison, which rises steeply from huddles of brick terraces from which fans could walk to a game, is more of a pies-and-sheet-metal sort of place. We don’t want a palace, said Everton fans in the social media discussions they had with the stadium’s lead designer, the LA-based architect Dan Meis. They didn’t want to be Tottenham Hotspur, the club that built the Premier League’s last brand new stadium, nor did they want the luxury “cheese room” proposed (but never installed) in their shiny venue. Meis wanted his design to “grow out” of its dockland setting, not be “a spaceship landing”. At the same time, he says, he wanted “a bit of Hollywood”. The finished building, achieved with the help of BDP, a big international practice with headquarters in London, and the contractor Laing O’Rourke, consists of a curving silvery roof (quite spaceship-like, as it turns out), perched on a base faced in vertical brick strips. These refer to the nearby Stanley Dock Tobacco Warehouse, a leviathan that, when completed in 1901, was said to be the largest brick building in the world.

Everton’s new Hill Dickinson Stadium

The stadium sits tightly on its site, while seeking to exploit its position on a famous expanse of water. Concrete terraces, accessible to the public on days when there are no matches, look out across the Mersey. A long window offers panoramas from the internal concourse back to the city of Liverpool. A broad promenade runs along a neighbouring still-watery dock, paved with 36,000 granite stones, personalised by fans with their names and messages, under a grand portico formed by the oversailing end of the stadium structure.

Inside, the supporting joints and beams in concrete and steel are frankly displayed and, away from the premium areas, the concourses have a workaday feel. The most important part of the whole operation – the stands – are designed, says Meis, to recapture the “magical, historical” quality of Goodison. The aims are intensity and intimacy, with seats on the small side by modern stadium standards, and the rake of the terraces, at 34.99 degrees, fractionally within the legal limit of 35 degrees. Big girders, like something out of a shipyard, hold up the roof above, bringing some of the Goodison clank.

Seen from distant approaches, such as the mile-plus walk along the waterfront from the city centre or the slopes rising away from the river to the Everton area, the new stadium is a convincing object of pilgrimage and pride that holds its own among the big functional structures of past and present industry. Inside – although last weekend’s friendly didn’t quite recover Goodison’s roar – there’s reason to believe that, as a fan put it: “It’s going to be loud.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

There are some kinks that may or may not be ironed out, including congested concourses and skimpy public transport. It remains to be seen what the outdoor spaces will be like when wintry winds pick up, although considerable efforts have been made to mitigate them – even on a mild August day, there were blowy spots. The encounter of shine and grit doesn’t, architecturally speaking, always come off. The brickwork doesn’t really recall the mighty old warehouses, being assembled in prefabricated panels via factories rather than laid by hand; it looks papery rather than monolithic.

But it is a great thing to have a stadium on the water, and the derelict surrounding areas are already sprouting opportunistic bars with impromptu pavement tables, as if this were Naples. The pity is that heritage and football were ever put in conflict. In a better world, the stadium might have been built on one of the many empty sites in the area, such as nearby Clarence Dock, long ago filled in and closer to the city centre, which would have left both Unesco and the Everton fandom happy. This, though, was never on offer by the Peel Group, also the owner of Clarence Dock – which has more lucrative plans for it.

Photograph by Tom McAtee