You rush for the station but the faster you go, the further it gets. Even if you do reach the platform, your luggage has vanished, the train has departed or there never was a train in the first place. You implore indifferent bystanders for help, becoming ever more Cassandra-like in your insistence that something awful is about to happen, until the station turns into a theatre and someone in the audience shouts “fire!”, and that someone turns out to be you.

Even in the 16th century, people dreamed of fires in the playhouse. To be suddenly naked in a public place was a common Elizabethan nightmare. Later, 17th-century protestants urged the Lord’s Prayer and more every night before bed to keep the devil’s ghosts, mice and flapping birds out of one’s sleep. Samuel Pepys dreamed his wife died after quarrelling with her over the dog and Charles Dickens had recurring nightmares of the Staplehurst train crash in which he was uninjured. It is shocking to think how long our nights have been dominated by similar dreams.

Or is it? A show at Bethlem Museum of the Mind, situated in the grounds of the Bethlem royal hospital, puts the focus on hospital dreams in the final hours between sleeping and waking. The great surprise is that they are more familiar than anyone might have guessed. Images on display, many made by former Bethlem patients suffering intolerable anguish, depict recognisable night visions: of beetles crawling over skin, the sight of oneself levitating high over the bed, the struggle to get to the light through curtains or veils.

Anyone who has ever spent a restless night in hospital, woken in the small hours by staff handovers, the sound of other patients, the hum of monitors, sudden alarms, self-consciousness, fear or hyper-alert curiosity will know how shallow are one’s dreams. Not quite asleep nor fully awake, the dreaming mind is transparently affected by environmental events. A nurse once told me that the commonest dream on her ward was the old cliche of teeth falling out: terrible insecurity, total lack of control.

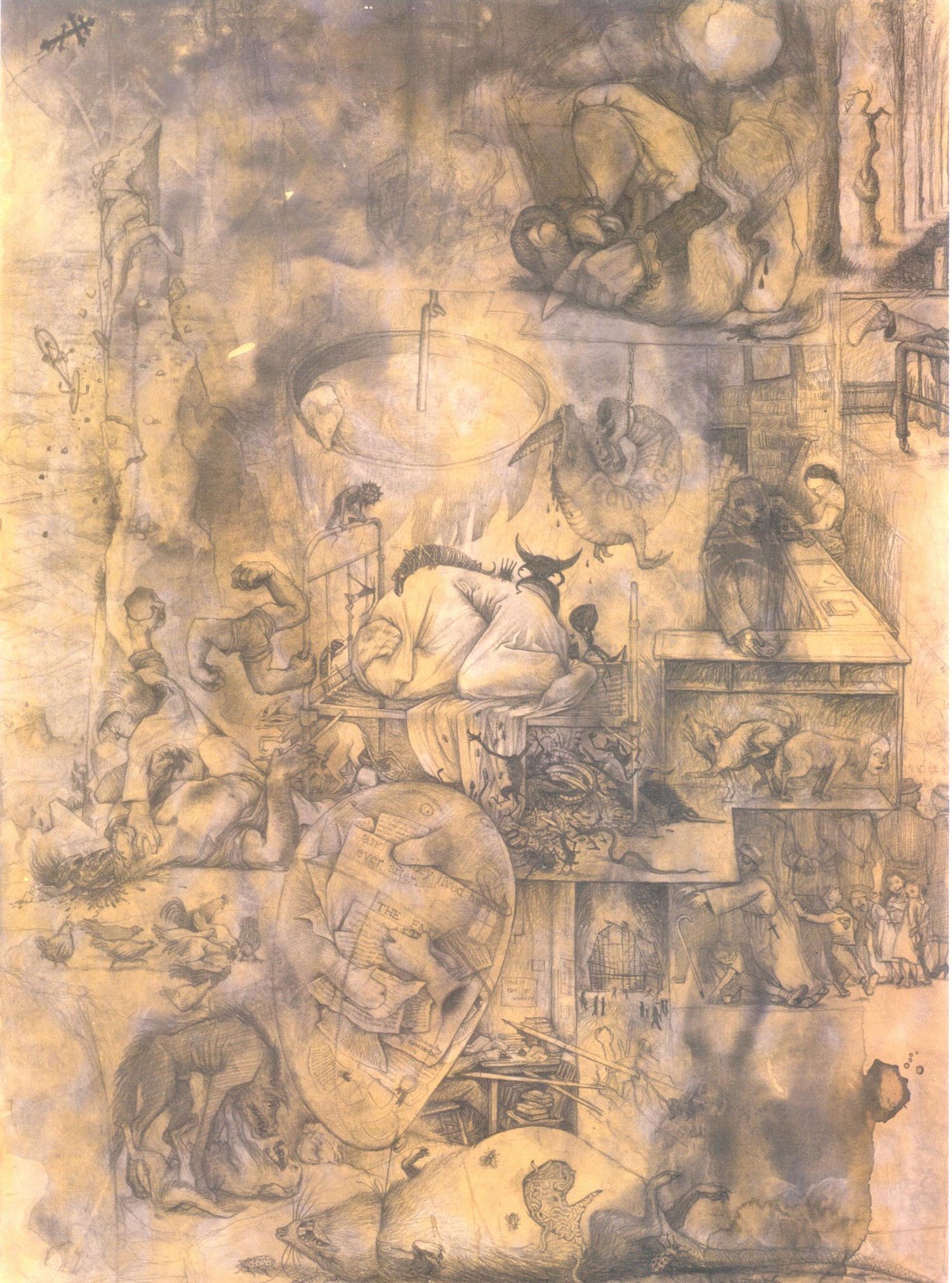

‘Raw, unmediated experience’: Nightmare, c.1953, by William Kurelek

But, at Bethlem, the dreamer is potentially enduring nightmares even while conscious. Allan Beveridge dreams of flying high above the terrible barbed wire of an internment camp in his pyjamas. George Harding pictures himself sleeping, smoking and dreaming, in the tradition of the US artist Philip Guston’s celebrated Painting, Smoking, Eating, but surrounded by weird exhalations and a couple of attendant cats. Charlotte Johnson Wahl, mother of Boris Johnson, depicts hands (printed with her name) perpetually reaching for help.

They are among the 20th-century artist-patients in this show, who include the visionary Madge Gill, a working-class autodidact from Walthamstow whose teeming drawings and embroideries attracted crowds at the last Venice Biennale. Gill wandered the wards by night, reversing the ordinary rhythms; women drift up and down staircases, expressions fixed, in her sleepless fantasies.

The Canadian artist William Kurelek admitted himself to the Maudsley (sister hospital of the Bethlem) in 1952 on a trip to London. The most significant painting he made as a patient is undoubtedly The Maze, which looks inside the many chambers of his brain, like the rooms of a doll’s house, to discover staring faces, crows and rats, village dances, peace marches and a solitary child, sitting hunched on a prairie. It is a justly famous image, midway between art and self-diagnosis. But the pencil drawing in this show, made upon waking from sleep, may speak to many more people.

It shows the artist holding his psychiatrist’s head by the hair and pointing to a further head pegged up on the wall, a diving helmet to which is attached a tattered remnant of self-portrait. What is the doctor doing to help his patient? Two words are written in block capitals on every brick of the wall behind them: sympathise; understand. The doctor is achieving nothing at all.

The drawing is rapid, coarse, an urgent record. Images are barely accomplished

The drawing is rapid, coarse, an urgent record. Images are barely accomplished

The drawing is rapid, coarse, an urgent record. We are not talking about Coleridge hastening to write down the deathless lines of Kubla Khan on waking from sleep, as he claimed. Most of the images in this show are barely accomplished. This is raw, unmediated experience by comparison to surrealism’s shrewd invention of a supposed dream world.

Bethlem was where the Victorian painter Richard Dadd RA lived out his later years, after killing his father, before he was transferred to Broadmoor. His unnervingly smug self-portrait hangs in the permanent collection, alongside the anthropomorphic cats of the Edwardian illustrator Louis Wain, once a household name. Can we see disturbance in these images; conversely, are they more interesting because of it? These are the perennial questions raised by such displays.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Alongside visual images are the dream diaries of the Bethlem psychiatrist Dr Edward Hare, sustained over several decades until the 1990s. In one dream, he congratulates Christopher Wren on the design of St Paul’s Cathedral. This is in happy contrast to the c.1830 ink drawing of Jonathan Martin, brother of the more famous apocalypse painter John, in which debauched London goes up in flames.

Martin was committed for trying to burn down York Minster in protest against church corruption. This image is surely a dream of another kind, and is where the fascinating proposition of this show enters: in psychosis, we believe what we see, hear, dread and hope, from the disappearing railway station to the vision of London burning. As so it is with our night’s dreams.

Between Sleeping and Waking: Hospital Dreams and Visitations is at Bethlem Museum of the Mind, Beckenham, until 22 November

Photographs courtesy of Bethlem Museum of the Mind