As the spring of 1938 unfolded, Nazis surrounded Sigmund Freud. He had been resolute in his decision to remain in Vienna, but in the months after the Anschluss, his home was ransacked, his daughter arrested, and a Swastika was hung over his door. It was time to leave.

The Freuds arrived in London in June, and by September they were installed at 20 Maresfield Gardens in Hampstead, now the Freud Museum. Freud’s library, with his hundreds of Roman, Egyptian and Chinese antiques, was painstakingly re-assembled and organised as it had been in Vienna.

The woman Freud entrusted with his home, workplace and most prized possessions was his housekeeper, Paula Fichtl, who fled Vienna with the family. Fichtl had worked with the Freuds for a decade: running the household, showing patients into the consulting room. “She knows this place better than all of us,” Freud said. “For every tiny piece, Paula knew the right place.”

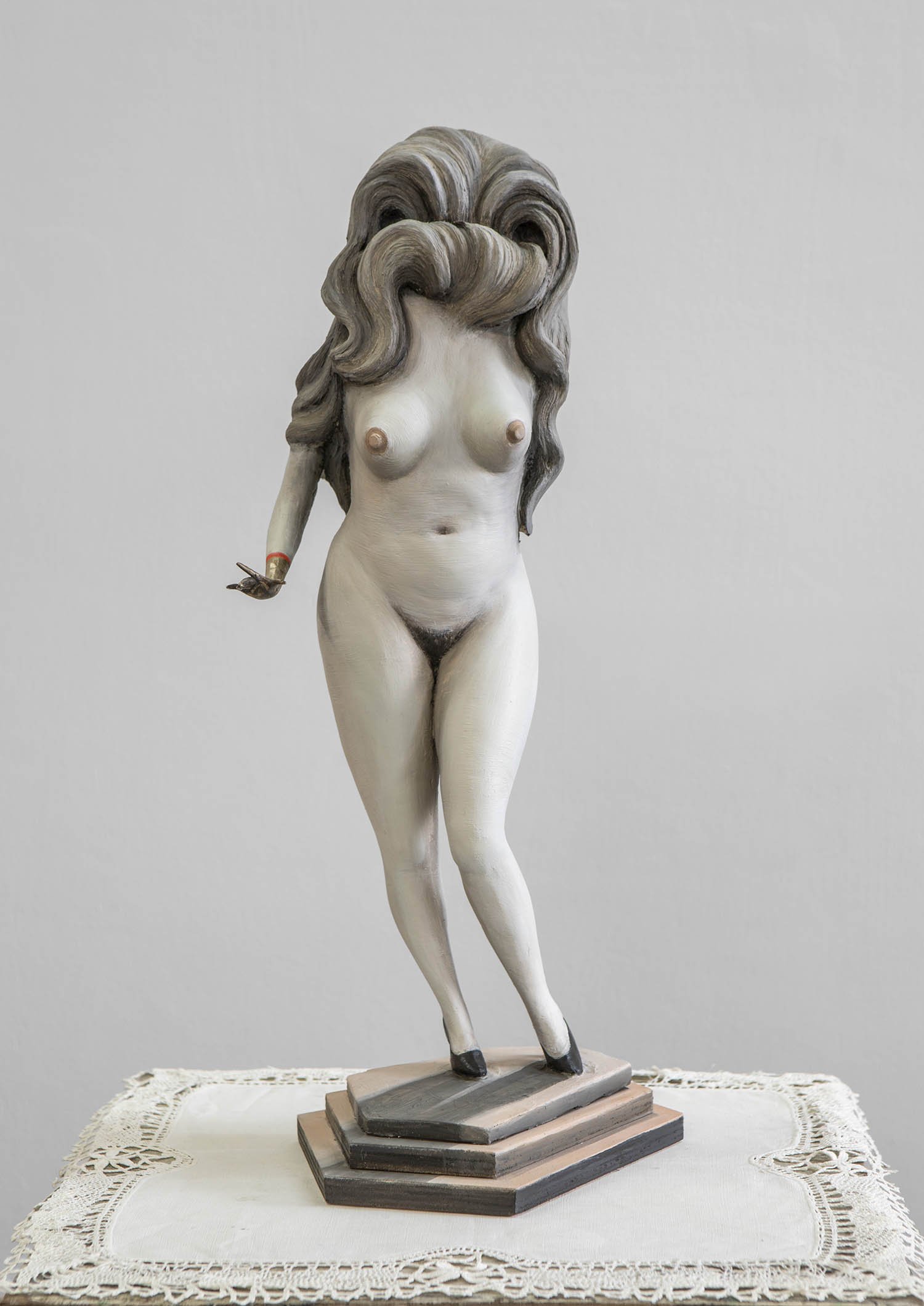

Paula Fichtl. Main image: Cathie Pilkington’s miniature naked woman, with no head but voluminous hair

Housekeeper, a new exhibition at the museum by the artist and sculptor Cathie Pilkington, gives Fichtl a new life. Pilkington is known for her witty, surreal work: this is not a biographically faithful undertaking, but a playful, fanciful one. What if the housekeeper were a less dutiful, more mischievous presence?

In the dining room, the atmosphere is eerie. Pilkington’s unsettling 2003 sculpture Curio shows an ageless girl sitting at a dressing table, surrounded by glazed figurines. Her expression is vivid but inscrutable. On top of one of Anna Freud’s cabinets is a statue of a defecating dog.

In the library-cum-consulting room, already crowded with Freud’s objects, it’s not immediately obvious which are Pilkington’s. If the first room plays with the Freudian concept of the uncanny, the second touches on displacement. A Roman bust on a mahogany plinth has been ousted by a miniature naked woman with no head but voluminous hair. On the desk, among upright, almost phallic male figurines, is a woman made of breasts. A horse’s head and a faceless female bust appear on a table of ancient artefacts, disembodied plaster limbs lie on a square of carpet. An owl with breasts surveys the room from a corner.

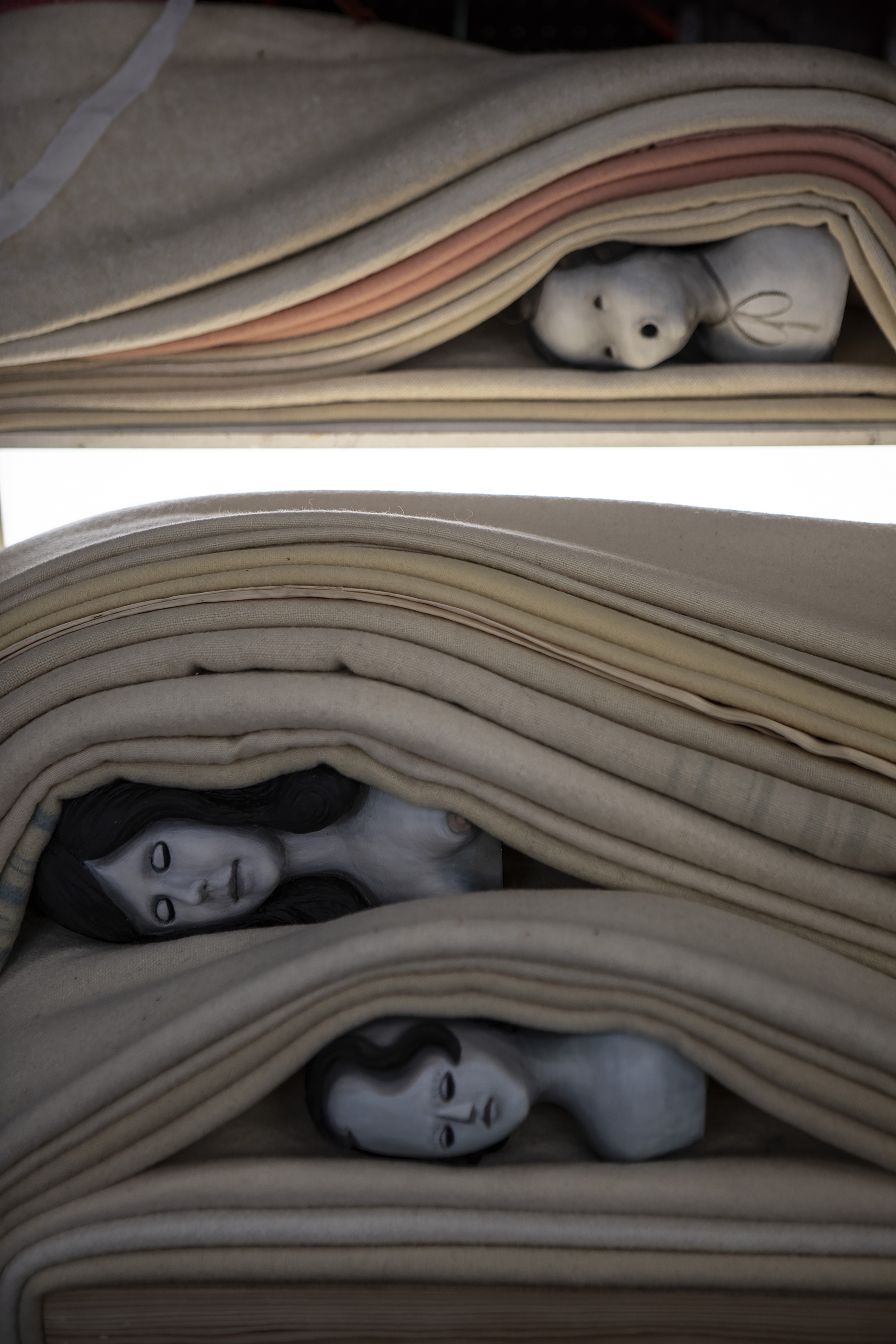

Cathie Pilkington’s Strata contains sculptural heads ‘piled under layers of fabric that imitate a geological cross-section’

Pilkington has repurposed Freud’s bedroom as a “storeroom” for the housekeeper, and it is crammed with an overwhelming jumble of work. Here we are in the realm of the dreamscape. Drawings line the wall, figures sit almost forgotten in corners, half-finished clay works lie on a paint-splattered table. On a dusty pinboard are pictures of a young Fichtl cuddling the family dog; in old age, proudly standing by the late Freud’s collection. In a glass cabinet lining an entire wall, a new work, Strata, contains sculptural heads, beaten-up footballs and soft fabric limbs piled under layers of fabric that imitate a geological cross-section. Symbols and images recur: the faceless woman, the horse’s head, the owl.

Here, Pilkington’s work amasses references to other artist s interested in psychoanalysis: Louise Bourgeois, Hans Bellmer. Bourgeois once wrote that Freud’s antiques reminded her of Madame Tussauds: nostalgic, kitsch. She called them his “toys”. In a final room, Pilkington places a Roman alabaster statuette of a baboon, among other artefacts, next to her own family heirlooms: Hummel figurines. There is a skiing boy, a girl with a basket, a dog with pleading eyes. A neon Post-it note beneath them reads, in neat script, “Collection of Cathie Pilkington”.

Housekeeper is at Freud Museum London, NW3; until 1 March 2026

Photographs by Perou

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy