Mid-morning in the Valley of the Kings and the temperature is soaring. Stray dogs huddle in the cramped shadow of a rock. A party of 10, here to be shown an ancient Egypt that is off-limits or overlooked, we fan ourselves furtively against the heat at the top of a staircase that plunges down to the tomb of the last pharaoh of the 18th dynasty. It is sealed. Somebody must volunteer.

I cannot help myself, visions of Howard Carter finding Tutankhamun dancing in my head. The one-storey house where Carter lived is close to our hotel on the west bank of Luxor. Someone makes a dark joke about The Mummy’s Curse. Two Egyptians in long brown robes lead me by the hand down the steep steps to this secret underworld, last resting place of Horemheb, who was Tutankhamun’s general before ruling as pharaoh more than 3,300 years ago. But the entrance turns out to be an iron door, the tomb only closed to the public for a few more years of excavation. All I need to unseal its padlock is a key.

What awaits, however, is so staggering that we all fall silent. Vertiginous stairways descend into chamber beneath chamber, down and down into the baking rock beneath the valley. The walls twinkle with hieroglyphics that appear silver, pink and gold in the lamplight. Figures carved in painted bas-relief glow against blue-grey backgrounds: gods in turquoise tunics; white crowns and crimson necklaces; women in sheath dresses printed with flowers; thrones of marble and gold. The lower we go, the more stunning the colours. One chamber has a midnight-blue roof scattered with constellations of bright stars.

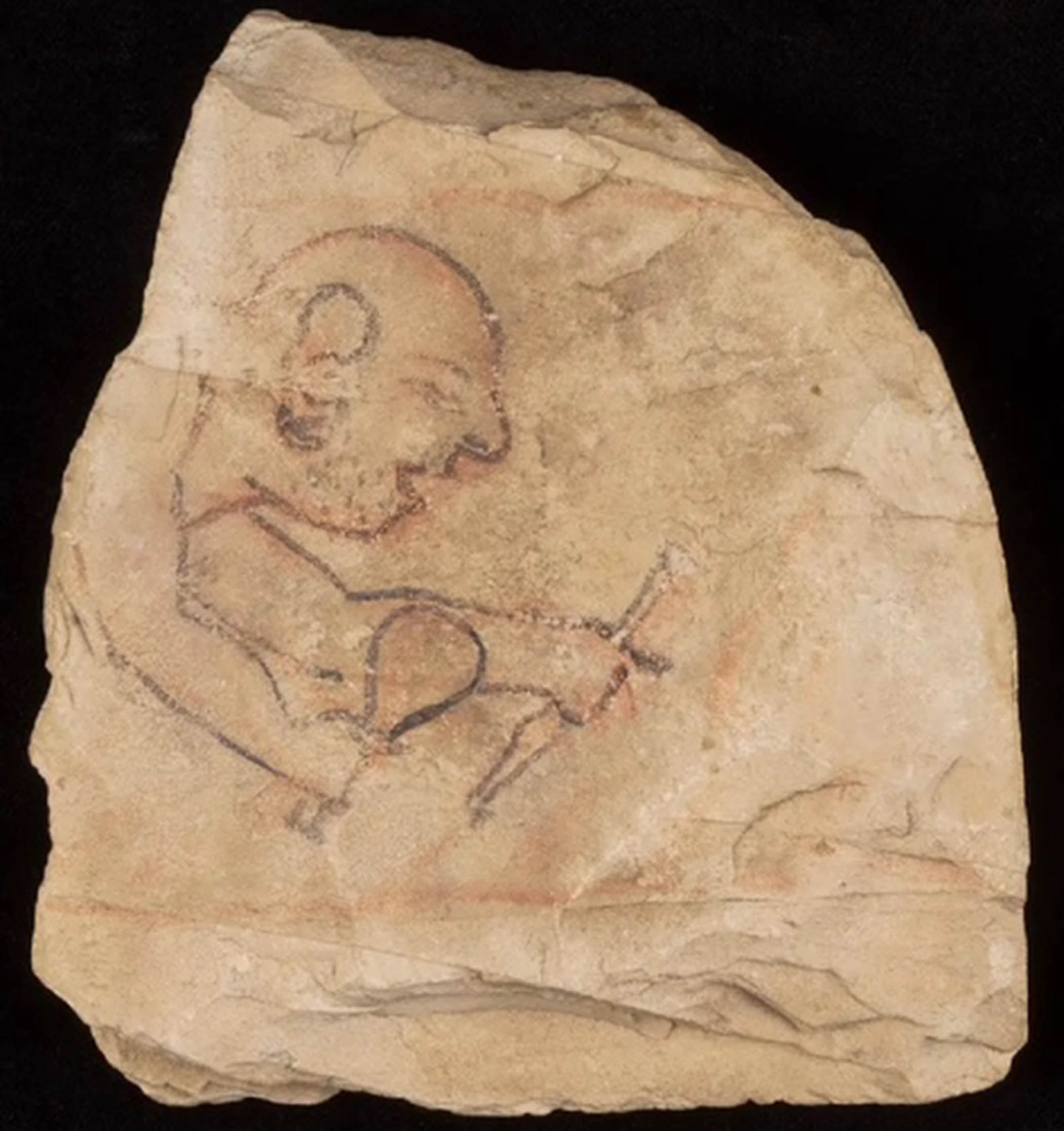

An artist’s sketch of a fellow sculptor, complete with big ears and five o’clock shadow

Horemheb’s sarcophagus in the final chamber is carved out of obdurate red quartzite. Its lid was already broken when the tomb was discovered in the 20th century, choked with debris washed down the valley by centuries of floods. Inside were some human remains, none of them identifiable, but the mummy was gone. It has never been found.

Around the sarcophagus is something far more unique: a frieze of drawings that are not yet complete. Birds strut forward, red sketches beneath firmer black outlines, a kneeling figure, the undulations of a river. There are corrections, adjustments, experiments going on right before your eyes. Horemheb’s rule probably lasted about 14 years, yet they clearly didn’t finish his tomb in time before it had to be sealed up for ever following his embalmment and funeral. After all these millennia, evidence of a missed deadline: it still feels quick with the living hands of the artists.

Which is why we are here, brought by Helen Strudwick and Neal Spencer, eminent Egyptologists of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, to find the artists of ancient Egypt. To discover who carved the quartzite, gilded the crowns, drew all those cats and dogs and human figures, who crawled up a ladder to cover the night sky with painted stars, or crouched down low to draw a foot with fetchingly upturned toes.

You realise they did it in unimaginable conditions, to start with. Today’s temperature has reached 45C (113F) outdoors. The deeper they went, the hotter and more airless these chambers beneath the valley. There was no bottled water, nor anything to light the way through the obliterating darkness except for small and unreliable oil lamps. Even now, a temporary power cut can leave an excavation team in alarming blackness, as Strudwick knows from decades of excavating sites around Luxor, where she is greeted everywhere we go.

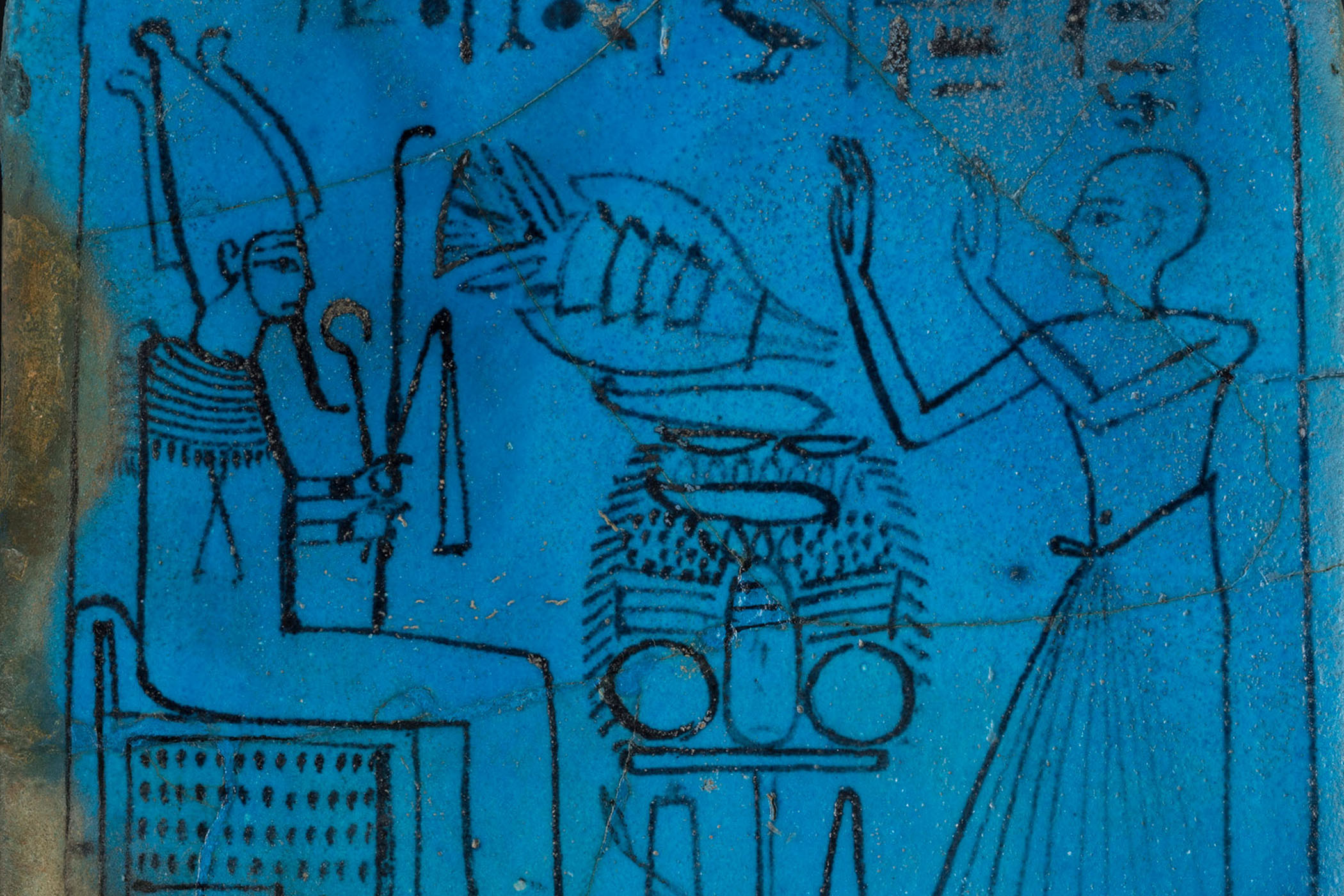

An ‘active image’ painted on a wall

Strudwick and Spencer are devoted to these exceptional moments where the hand of the artist appears, however briefly, between one grand pharaonic spectacle and another. They see the individual touch in the painting of a daffy duck, the sculpture of a careworn face, the amazingly hyperreal statue of a stout vizier carved in wood. They show us the way one sculptor can create a perspective through a doorway in the shallowest relief, while another can carve sunrays so they appear to illuminate the whole wall. We soon begin to see that Egyptian art is never the same and far beyond the caricature of sideways-striding figures.

Staircase, passage, side room, chamber: every wall is covered floor to ceiling. The artists must have been different ages and heights. Once you start to look at the art this way, through the lives of those who made it, actual beings spring up: the apprentice who is botching a parade of mourning figures; the older artist who corrects them; the supervisor who leans over and crosses one out.

Not only heat, but speed and constant noise surrounded the artists above and below ground. Tombs and temples must have been buzzing with workers. Boats arriving from the Nile bearing loads of carefully chosen basalt and granite; sculptors and architects sweating over their projects; mud bricks being manufactured exactly as they are today. Records show that security guards checked suppliers and staff in and out of the valley in rigorous logbooks, monitoring exactly who knew about this most secret of locations, the underground kingdom of the grateful dead.

For ancient Egyptians truly seemed to believe things could only get better once you were deceased, that the afterlife was the place to be. But to get there you had to pass through the underworld. With you went all kinds of material needs, ritual offerings and prayers to the gods, in the forms of magical images, which is where the artists come in.

This painting of geese is the oldest known image of a recognisable bird species

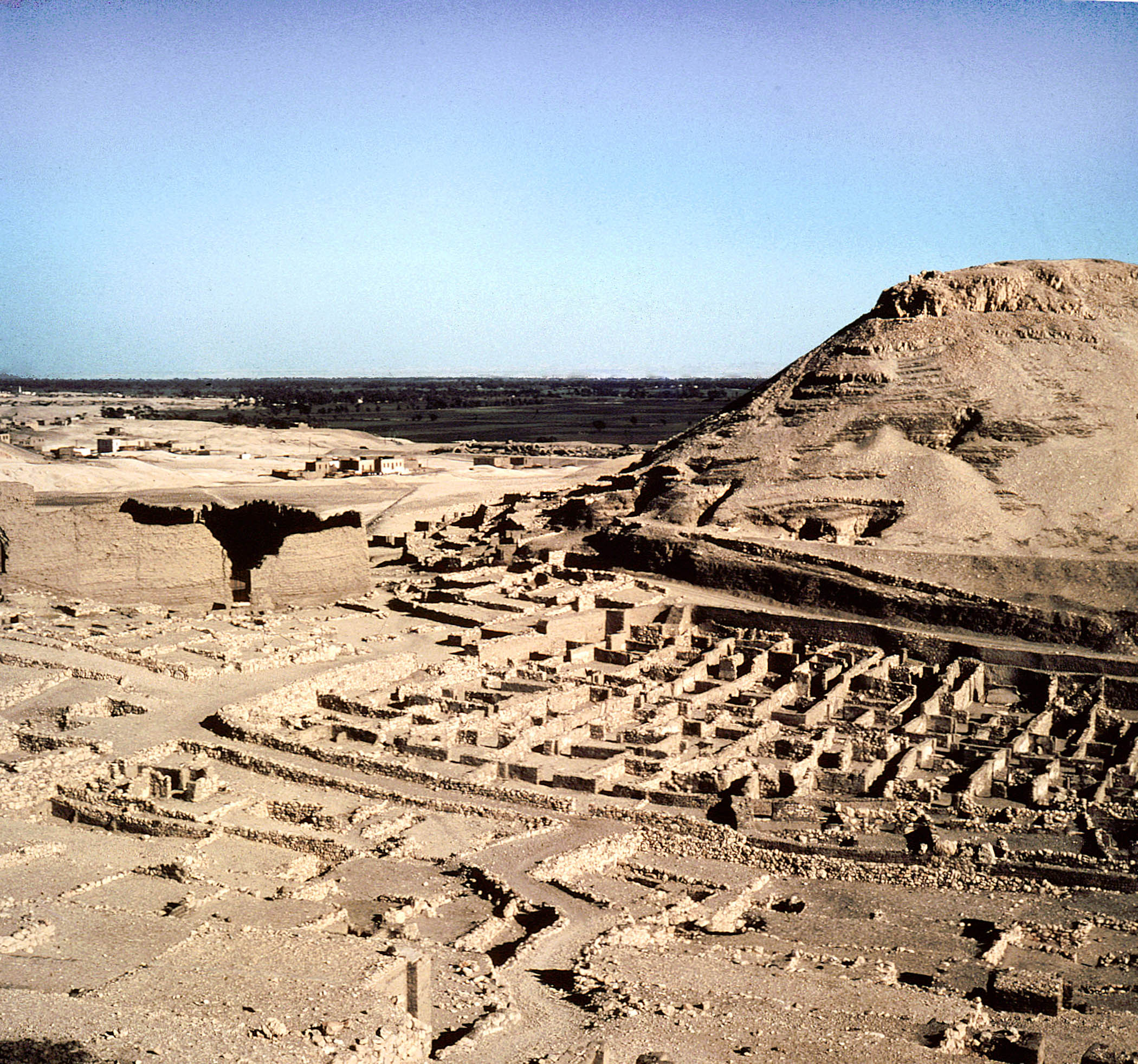

We had gone at daybreak to the little town where all these people who created the Valley of the Kings were housed. Our van climbed up through red rocks, outlandish as Mars. Deir el-Medina was so secluded that nobody knew the artists were there. Each day, they had to trudge over another hill into the valley before they even started work. A rest house stood on the summit for exhausted workers stumbling home.

Some of the houses run to three rooms, even a cellar. Hieroglyph records tell of neighbourhood arguments, gatherings, disputes over wages. The walls that heard it all extend into the distance. But it is the tombs they made for themselves, and not their overlords, that offer another strain of art. Here you can identify actual species of duck and palm. A black-and-white cow jaunts along one wall like a pantomime Friesian. There are noonday shadows. In life, you had a shadow; when you are dead, it becomes disconnected from you. An image of such a wraith seems to exit one tomb like a ghost.

Just above the town is a small but graceful Ptolemaic temple, surrounded by a mud-brick wall that still stands, with a certain sag to give it stability against flood and earthquake. Beyond is a treasure trove of revelations: a pit full of limestone ostraca. These are little chunks of stone on which to draw messages, the ancient Egyptian equivalent of envelopes or Post-it notes. A son is taking over his father’s job. A bloke drank too much and didn’t make it to work. Here’s a quick family tree, a portrait, or a brusque order for a new window.

Best of all is the ostracon from Deir el-Medina of a stonemason going at it with his chisel, head shaved against the heat (all those Egyptian pharaohs are wearing ceremonial wigs, incidentally). He has bristly stubble and big ears, and he is either laughing or singing. There were two shifts each day in the valley: four hours in the morning; four in the afternoon after a bread lunch. His five o’clock shadow is so pronounced this must be the afternoon. Somewhere between portrait and caricature, it is an image full of mirth: an affectionate likeness of one artist by another.

Deir el-Medina, home to the pharaohs’ tomb artists

The stonemason will be on show in Made in Ancient Egypt, curated by Strudwick, at the Fitzwilliam from 3 October. It is no overstatement to describe this exhibition as epochal. This is the first show ever to focus upon the people who actually made art for the pharaohs, or how they did it. How, for instance, did they come up with the exquisite colour known as Egyptian blue, the world’s first artificial pigment, made using silica, lime and copper compounds fired at stupendously high temperatures? How did they create the glass eyes that glitter in Tutankhamun’s mask? Where did they get the wood to smelt all the gold, bake all the bricks? The Fitzwilliam has conducted its own experiments, so that we now know, for instance, that it took 64 hours just to carve the museum’s own comparatively modest Egyptian coffin.

But something even more momentous could come out of this exhibition: a completely new history of art. We grow up learning about art – if we do – from the Lascaux caves to Picasso, say, via the evolution of ancient Greece and China, the Indus Valley and Rome. But ancient Egypt never gets into the story. There are no legendary artists, no movements, only royal or religious conventions and gigantic stone pharaohs. Plato believed that Egyptian art had literally remained the same for 10,000 years and his claim has lingered ever since. Yet ancient Egypt had a word for groups of artists – “hemut” – and it had a word for sculptors: “sankh” means the “one who gives life”. Some artists were famous enough to have surviving names.

The Fitzwilliam is showing a stele for a “master artisan” named Irtisen. His voice emerges through the hieroglyphics carved on the tablet; he knows how to depict male and female figures, he says, how to create colours that will last, the right poses and proportions. He will only transmit this secret wisdom to his eldest son. At the bottom of the slab, a pair of doors stand open to reveal Irtisen and his wife sitting cosily together at a table.

Statue of Nefertiti, Tutankhamun’s stepmother

When Akhenaten decreed that a whole new capital city be built in 1346BC, known today as Amarna, he appointed a man named Thutmose as his royal sculptor. German archaeologists, coming upon the workshop of Thutmose in 1912, were stunned by his plaster studies of Akhenaten and his wife, Nefertiti: nuanced and naturalistic portraits of actual living people, speaking likenesses, the intimate basis for some of the most famous works of hieratic public art.

There exists, in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, a tremendous painting of six geese in a garden. It contains the oldest known image of a recognisable bird species, the greater white-fronted goose. Each goose is exquisitely characterised in mid-peck or mid-strut by this marvellous painter, and what his masterpiece reveals is that Egyptian artists more than 4,000 years ago could produce works of sharp but elegant realism for their masters at the drop of a feather. But tastes changed, and styles shifted. It is what we in the west would call a lost movement.

A wall of the immense temple complex at Karnak, hidden around a corner easily missed at twilight, is carved to show the possessions of some long-ago pharaoh: vases, urns, cups and graceful dishes. One of our party observes that it resembles a remarkable shop. Every object is arranged on a shelf, in shallow relief, gorgeous flower arrangements in some of the vases; all the elements of Thomas Wedgwood’s shapely Egyptian ware prefigured thousands of years in advance.

And we never stopped spotting faces wherever we went, despite Spencer’s patient explanations: these were not portraits, but portrait types. For comparison, think of Roman emperors, of whose actual appearance we cannot be sure. Yet there were pharaohs with outsize ears, double chins, pronounced laugh lines, distinctive marks of woe. Hooded eyes, a higher forehead, an epicene figure: we seemed to recognise them in person, so that it was hard to believe we were never looking at a likeness.

Painting of a monkey scratching a woman’s nose – a parody of a funeral ritual

This came to a head, literally, over the extraordinary elongation of Akhenaten’s face – you would know him anywhere – but more specifically the skull of Tutankhamun, his probable son. Were we really to believe that this family shape was just a new advance of style? We went to KV62, Tutankhamun’s surprisingly small and modest tomb in the Valley of Kings, this time surrounded by equally awestruck crowds.

Rulers could be planning their tombs for years and suddenly they would have to be made ready for someone else. This one is hastily painted, presumably in the 70 embalming days between the young pharaoh’s death and burial. In all probability, nobody expected the teenage Tutankhamun to die. There is even some evidence that his golden mask, the very symbol of ancient Egypt all over the world, was originally conceived for his stepmother, Nefertiti.

This tomb does not descend into the earth, chamber below chamber. The paintings are broad brush and cheerful, as if done for a child. But as you turn to leave, there is the sudden and tremendously affecting sight of Tutankhamun himself, or at least his small body, dark and wizened, laid to rest in a side chamber on a bier. And there, at least to our eyes, was the forensic evidence of the elongated back of his head.

This tomb was robbed thousands of years before Carter unsealed its entrance in 1922. The art inside, a form of prayer to the gods, never made to be seen again by human eyes, was ransacked by robbers at least twice, and quite soon after Tutankhamun’s burial. Poverty overcame fear of divine or pharaonic retribution; famine, says Strudwick, having at least something to do with tomb raiding. But consider, too, the ubiquitous spectacle of plenty. To move around Luxor is to see it in every towering column and gigantic statue, every pharaonic head still bearing traces of Egyptian blue and gold, every hieroglyphic transmitting its message of triumph, glory and wealth.

The invention of cuboid statues allowed figures to sit with knees up

Hieroglyphics are talking pictures. Suns, birds, feathers, faces, crouching lions, open arms, upright cats. There are no spaces between them, there is no punctuation; you know which way to look because of the direction of the heads. Seen carved or painted across Egyptian walls, they seem to speak to each other, telling their stories back and forth. These are active images.

When the sun strikes the top of Queen Hatshepsut’s obelisk at Karnak, you can see it miles away across the desert. You don’t even have to be standing right below to read the family propaganda it transmits because the hieroglyphics are so clear and elegant, and cut so deep into the needle of pink granite that is almost 29 metres (95ft) high.

So much of what you see in ancient Egyptian temples is made to change with the ever-shifting play of light. Shadows fall at starkly different angles in the heat, activating relief carvings of flying arrows, soldiers and raging bulls. The journey of the sun across the sky – a deity itself, indeed the deity to Akhenaten – changes the look of life and art.

Always, on this journey, we were looking for the moment when an artist broke rank and changed the rules. And we found it everywhere. A sculptor spreading the wings of a vulture not just across the side of a basalt tomb but at right angles around a corner, as if to protect the departed. A hieroglyph of an eagle that is just taking flight into reality, breaking free of its rule-book form. An owl that turns to look at you with its curiously human face and fixed gaze. There is no doubt that some artists were just abundantly more gifted than others.

Head of the coffin of Nespawshefyt, a scribe

The artist’s mind and hand are there in the brilliant invention of cuboid statues, seated with their knees up, ingeniously creating a whole new flat panel on which to continue these ceaseless stories in hieroglyphics. They are there in the vein of humour running through the caricature of the stonemason and the painting of a monkey tweaking a woman’s nose in a parody of the supposed “mouth-opening ceremony” at funerals. They are there too in the fabulous blue, white and yellow chevron-striped fish, with its swirly eyes and burbling mouth, that will star in the Fitzwilliam show. It is impossible to understand, even now, how this masterpiece came to be created out of matte glass.

A sandstorm rattles our walls that night. Dogs bark through the small hours. A camel tethered outside coughs at dawn. All is as it was, thousands of years ago. From a certain spot, you can see the astonishing Colossi of Memnon rising in the morning sun, vast but now shattered twin figures, faces lost to time. In the field next door stands the archway of some ruined temple.

Egypt is never-ending. It continues to yield its treasures for ever, buried like charms in a Christmas pudding. The excavations will never cease. Someone asked if there may be any more tombs to discover in the nearby hills, and our cherished experts just nodded and laughed. Put your hand in the ground, says Strudwick, and something always turns up.

At the temple of Ramesses II, also known as the Ozymandias temple, after the poem by Shelley, South Korean archaeologists are running the latest dig (the sites are apportioned internationally, according to all kinds of soft politics and hard cash). Everything they discover is numbered, itemised, digitally recorded. Before us on our last morning lie the toppled relics of Ramesses – his broken head, one curving shoulder, a huge fragment of torso.

A hyperreal statue carved in wood

Spencer reads Shelley’s poem aloud, with its resonant final lines: “Nothing beside remains. Round the decay / Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare / The lone and level sands stretch far away.” Looking at the temples, monuments and excavation sites proliferating all around us, we try not to laugh.

There is a vestige of Egyptian blue in Ramesses’s striped headdress, shattered on the ground. You see traces of it everywhere. In ancient Egyptian eyes, on tunics, describing the movement of rivers, striping colossal columns and their lotus leaf pediments. It is a blue like no other, rich and deep with hints of cerulean and occasionally turquoise. But we saw another blue on that final day.

It was lying on the ground: a little piece of ceramic bowl, cobalt blue, abandoned thousands of years ago by the last person to hold it. Left behind at speed, or so it seemed, this fragment was spotted by a fellow journalist who bent to look while members of the Egyptian dig hurried to the spot. And it turns out that they had left very quickly, all the artisans who lived in this place, and who only made this blue for a short time in the 18th dynasty. This had been their town, with its beautiful brick walls undulating, crinkle-crankle style, away into the desert. The town was only discovered in 2020 and is not yet open to the public. The Egyptians call it “the golden city”.

‘A cow jaunts like a pantomime Friesian’

It seems that Akhenaten had simply upped and left for Amarna. His workers had to follow. All the sculptors and painters, ceramicists, weavers and jewellers, all the scribes and those who drew the exquisite figures moving across the walls of ancient Egyptian tombs and temples had to go with the pharaoh and build him a new city hundreds of miles to the north.

Not far from this blue fragment was the most startling yet poignant sight I witnessed all week. A guard signalled to me to follow him, silently, among the narrow alleys and in through the ruined doorway of a house. There on the wall was a humble painting. A white semi-circle, spreading its rays across the small mud wall: the sun shining its light over the hidden home of the artist.

Made in Ancient Egypt is at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge from 3 October-12 April 2026

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Photographs by Laura Cumming, The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, Musée de Louvre, DalberaTal der Koenige, Getty Images