In 2016, the film-maker Jake Auerbach applied for German citizenship, a move that was at once straightforward and deeply complicated. His father, the artist Frank Auerbach, had left Berlin in 1939 as a boy, one of six Jewish children who were sponsored to travel to Britain by the writer Iris Origo, and as a consequence, it seemed likely that Jake would get a new passport. But this had to be set against the fact that after saying goodbye to them, Frank never saw his parents again. Their letters to him stopped; eventually, he would learn they had died in Auschwitz.

Jake decided to go carefully, at first not telling his father what he was up to. “I wanted to see what was possible,” he says. “But then, after only a couple of months, the embassy got in touch to say it was confident the application would go through.” He remembers very clearly what happened next. “I was sitting for my father, and at the end of the sitting I said: ‘There’s something I want to tell you, and I want to know what you feel and think about it.’ I explained about the application. He was quiet for a while – about 30 seconds – and then he said: ‘I don’t feel anything, but I think it’s a good idea. It’s good to have options.’”

Documents almost in hand, Jake thought it would only be good manners to learn some German and again, this went down well with his father. “Frank loved the fact that I spoke a bit,” he says. “During the [Covid] lockdown, I instituted something that had never happened before, which was that he would call me every morning so I could check he was OK, and those conversations, once I got a grasp on the language, tended to start in German. When I started travelling to Berlin, he was so interested to hear about that, too, especially the food, which he missed, and thought unrivalled.” He smiles. “He would have had no interest in travelling to Berlin for this show. He wouldn’t even go into the centre of London for a show! But he knew it was happening, and though I can’t speak for him, I do think he would have been more pleased about having an exhibition in Berlin than in some other places.”

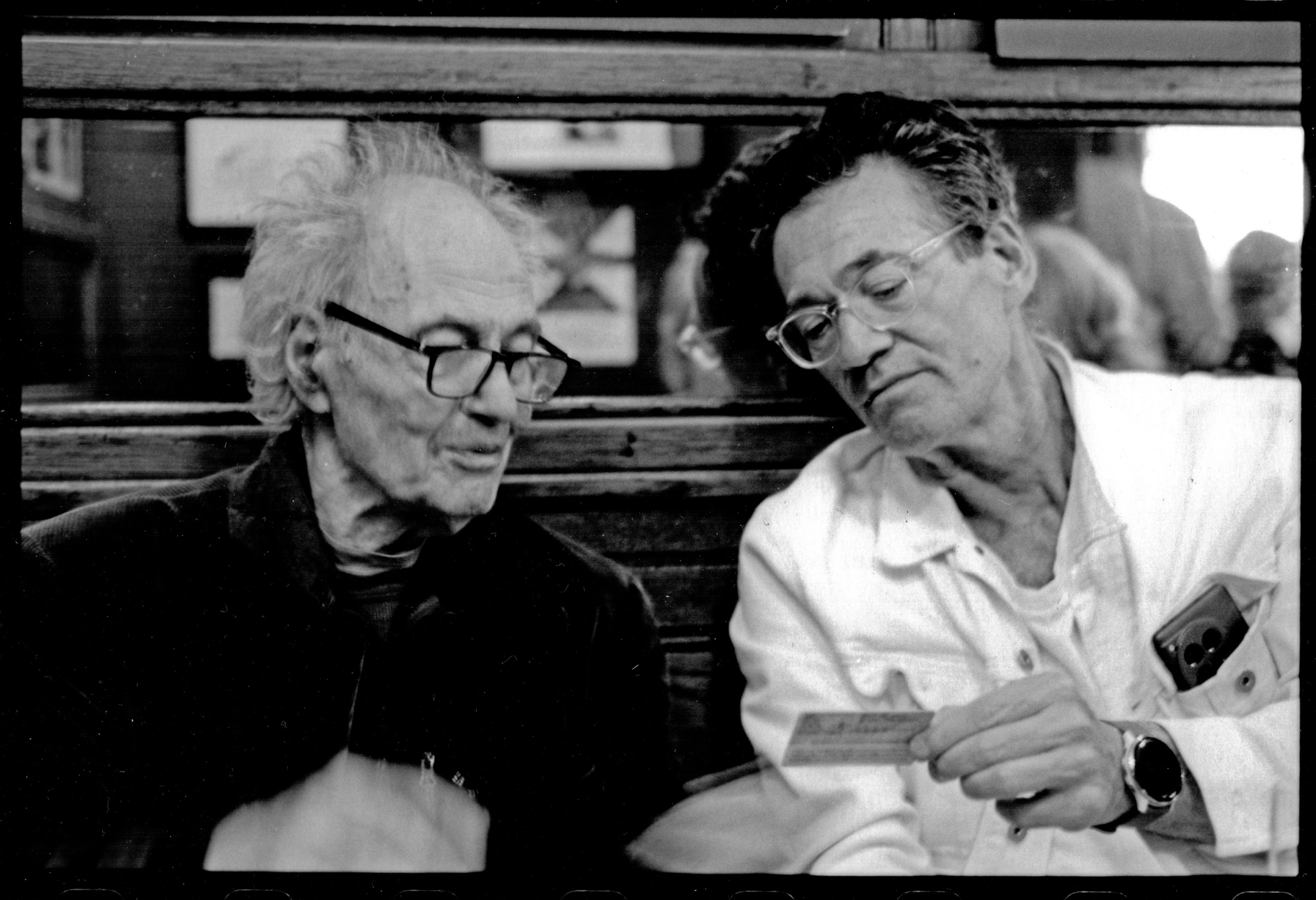

The show in question – the first since Auerbach died at 93 last November – opened in Berlin on Friday at the Galerie Michael Werner, and may be seen as a homecoming of sorts (while his father, contrary to popular belief, did return to Germany, he visited Essen and Hamburg, not Berlin). Curated by Catherine Lampert, a former director of the Whitechapel Gallery and one of Auerbach’s long-term sitters, it comprises 40 landscapes and portraits, the earliest dating from the 1960s, and the most recent from 2024. “It was his ambition to go with a brush in his hand,” says Jake. “And he almost managed it. The last painting [a self-portrait] was finished five weeks before he died.”

There are, he says, several popular myths about his father (the story Frank found most annoying was that he’d escaped to Britain on the Kindertransport). But his much-vaunted workaholism – it was said that he painted for up to 18 hours a day, seven days a week – was indeed a fact: “He said to me: ‘Why would I do anything else? This is the best game I’ve ever played.’”

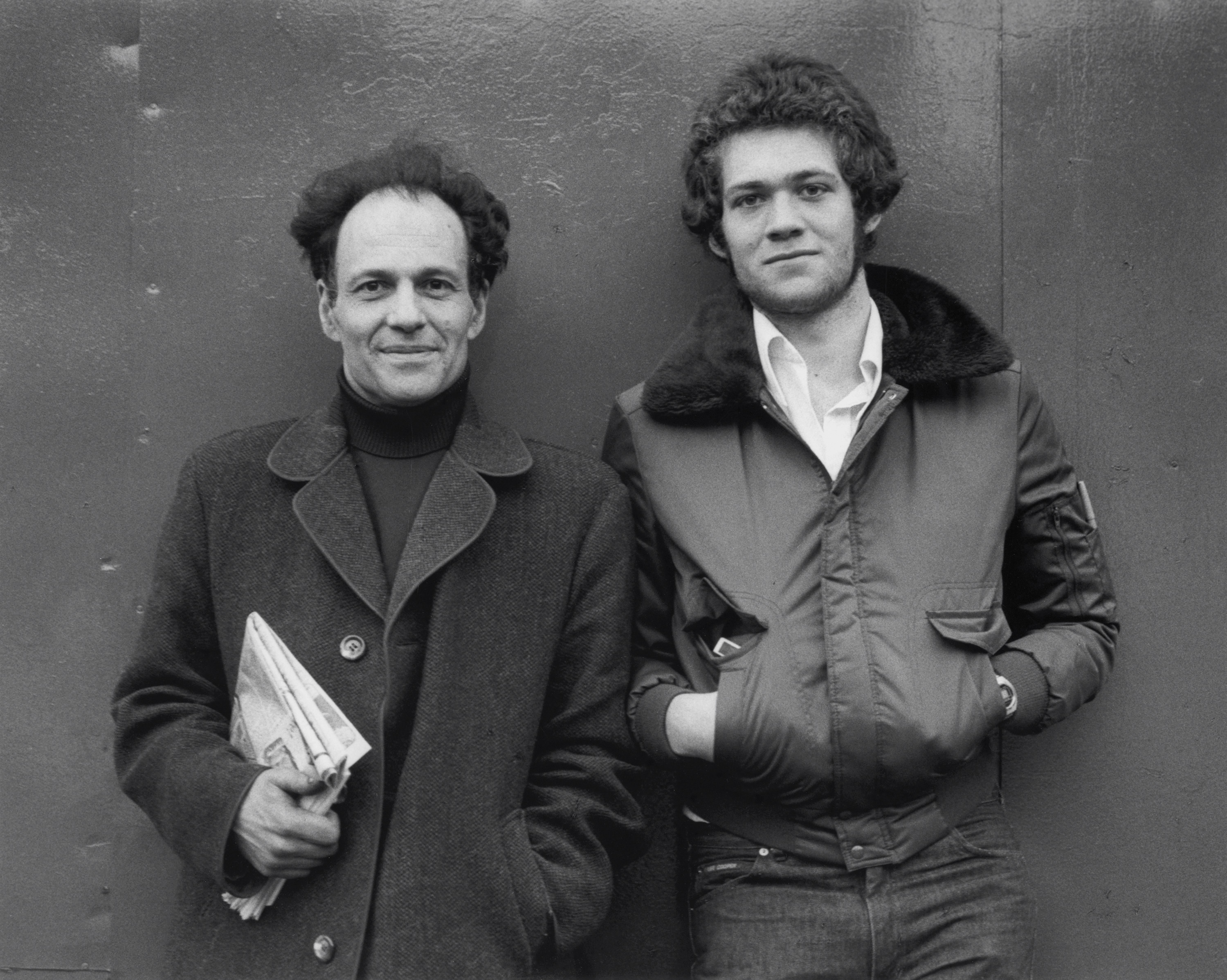

When we meet in a cafe near King’s Cross station, Jake has almost finished making a new film about his father, a documentary (I’ve seen an early version) that elegantly succeeds in dispelling the aforementioned myths. He wonders how he’ll feel once it’s finally done. “Making this film means he hasn’t really left,” he tells me, his hand around a mug of mint tea. “I’ve watched it with other people, and I can see them experiencing the impact of his loss – and occasionally, I experience it, too. But it hasn’t really hit me properly yet, I think.” He pauses, and I’m struck by his strong resemblance to his father. It’s in his features – especially in his smile – but also in his equable manner, the way he takes his time when he talks.

Last year was hard. Jake’s mother, Julia, also died, in January (she and Frank had been married since 1958). “They’d lived long and full – the fullest – lives,” he says, “and the end was as good as it could have been.” Was Frank afraid of dying? “I think he was scared of not being able to work, but I don’t think he was scared of death. At the end, he felt he couldn’t work, and he was ready to go.”

Among the portraits on show in Berlin is Reclining Head of Julia (2019-20), and anyone who still labours under the notion (another myth) that Auerbach was devoted to impasto, his paint so thickly layered that his pictures were hard to hang, will be struck by its lightness and lustre, effects that render it ineffably tender.

Jake’s film, the third he has made about Auerbach, tells the story of his father’s life from childhood. It is moving, and sometimes a little shocking, too. In old footage, Frank explains very plainly that his mother sent him to England with clothes and other items not only for the present, but also for when he was grown up; he tells us, too, of how the letters from his parents dried up.

But the sadness of these things is set against his enjoyment of life at Bunce Court, the Kent boarding school to which he was sent (it had a strong emphasis on the arts). For him, it meant freedom. His parents, he says on screen, were “stuffy” (his father was a lawyer). “I used to think, utilising a one-size-fits-all psychology, that this was my father’s way of dealing with the loss, turning it into a story, a pearl from an oyster,” says Jake. “But then you see the old Super 8 film of the school, and it does look heavenly. When I went to Berlin, I had a look at the apartment where my grandparents lived. It was obvious no one stuffy would have lived there, and my grandfather was one of the first lawyers to protect the writers of popular songs.” Survival, like memory, is complex: “I think… when you’re seven, you can’t really have a clear idea of who your parents are… I don’t think he was untouched [by what happened]; you see the way he talks about the things his mother packed for him. But I think he loved the school, too, and later, he loved his work.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

After school, Frank went first to St Martin’s and then to the Royal College of Art. It was there he met Jake’s mother, Julia Wolstenholme, though as his film reminds us, the couple were separated throughout most of the 60s and early 70s (Frank was living with another woman for some of this period).

Thanks to this, Jake didn’t come to know his father until he was 17 (he was five when his parents split up). Was there only silence in those years, I ask. “I get the impression from what I’ve discovered in the studio that Frank was sent photographs and things by my mother, but I had no contact at all. Then I got this letter. It said: if you’d like to meet, I’ll be in the studio at 7.30 most Thursdays. So, one day, I turned up. About six months later, we all three went to the theatre, and it [his parents’ reunion] started from there.” Was he the catalyst for their getting back together? “I might have been. I don’t know.”

What was it like getting to know Frank? “Life was richer afterwards. That first evening, he asked me if I wanted to eat, and we went to this Greek place in Camden that I think was a favourite of Lucian’s [Lucian Freud, Auerbach’s great friend]. It was a restaurant that made every effort to avoid passing trade – and then they tried to kill us with meze. So much food! We started talking. We had a number of shared enthusiasms: crosswords, films. It didn’t take long for me to start sitting for him, and that’s a good way to get to know someone. You’re there for two hours. There’s a job to be done. Mostly, it’s quiet. But we’d talk, too, unless the picture was near completion, when the temperature of the room went up and – this might sound ridiculous – I’d try to be as much me as possible, projecting a kind of energy that would assist him.”

Did Frank seek his opinion? “Occasionally, and if I was asked, I’d say what I thought. But I don’t think my opinion held much sway in the end. No one’s did.” Frank’s regular sitters were usually given pictures of themselves at some point – he regarded a portrait as “collaboration” between artist and sitter – and Jake is no exception. “Once, I was very appreciative, and I felt afterwards that was why he elected to give that particular picture to me. It’s a very wild one. I was in my twenties.”

But in the last years of his life, Frank was often his own model. Before we say goodbye, I tell Jake that ahead of our meeting, I visited Auerbach’s London gallery, where I saw four of the last works before they travelled to Germany. One was a self-portrait from 2024, and our conversation has made me feel all the more strongly about it. I remember how very clearly I could see the skull beneath the skin. How touching it is that this picture, among all his father’s paintings, now hangs in Berlin.

The Frank Auerbach retrospective is at Galerie Michael Werner in Berlin till 28 June. For details of Jake Auerbach’s film go to jakeauerbachfilms.com

Photographs: Harry Diamond/National Portrait Gallery, London;