Portrait by Suki Dhanda for The Observer

Gilbert Prousch and George Passmore have lived in the same house on Fournier Street in east London for more than half a century. When they moved in, the rent for a floor was £12 a month and there were just two curry houses on nearby Brick Lane. Black soot covered everything, even the Nicholas Hawksmoor-designed church whose spire looms malevolently over the neighbourhood.

Thirty-nine years later, in 2007, that same church was commandeered by Sir Nicholas Serota, the former Tate director who converted Bankside power station into the world’s most visited museum of modern art. Serota had given Gilbert and George a retrospective at Tate Modern, a first for British artists. In celebration, the pews of Christ Church Spitalfields had been replaced with circular tables and white-jacketed waiters. Midway through the evening, Serota, who has a reputation for being somewhat “headmasterish”, stood up and addressed the guests.

“At any one moment,” he said, of the previous decades, “Gilbert and George were in Fournier Street making work ... And it is an extraordinary achievement to see this consistent way in which they have dealt with … spunk … piss …” Everyone laughed; the artistic duo had got Serota to utter the words “spunk” and “piss” into a microphone. As the speech concluded, George stared straight ahead while Gilbert bowed his head like a monk.

The Tate is not the behemoth it once was, and the arts, as Serota recently made clear, has been “on standstill funding since 2010”. It is against a cultural backdrop of straitened circumstances that the Hayward Gallery launches its show Gilbert & George: 21st Century Pictures. The title is a pun on the movie industry, though the artists, now 81 and 84 respectively, claim not to have watched a movie since 1978 (The Deer Hunter, apparently). The exhibition will chronicle what we might term their late period. It will be their second retrospective at the Hayward and their 106th museum show.

When I arrive at the artists’ four-storey house, built for Huguenot silk weavers in the 18th century, its windows, frames painted yellow, are all shuttered. I am greeted cheerfully by Yu Yigang, who’s dressed in a well-ironed shirt and a pair of thick-framed spectacles. Yu met the artists at a 1993 show in Shanghai. A few years later, he moved in as their chief assistant. He does a lot for the pair: he navigates the internet for them, calls them cabs, assists them in the studio and even fixes their breakfast: “Two teas and one sandwich.” Previous studio assistants included Jake and Dinos Chapman, who went on to find success with the YBAs.

Yu leads me through the hallway, which is dark as a tomb and filled with pots (Gilbert and George have one of the UK’s largest collections of 19th-century ceramics). Eventually, we emerge into the yard and cross the threshold of their attached studio. They’re waiting for me at a table, inspecting a detailed miniature of the forthcoming exhibition, appearing almost like giants.

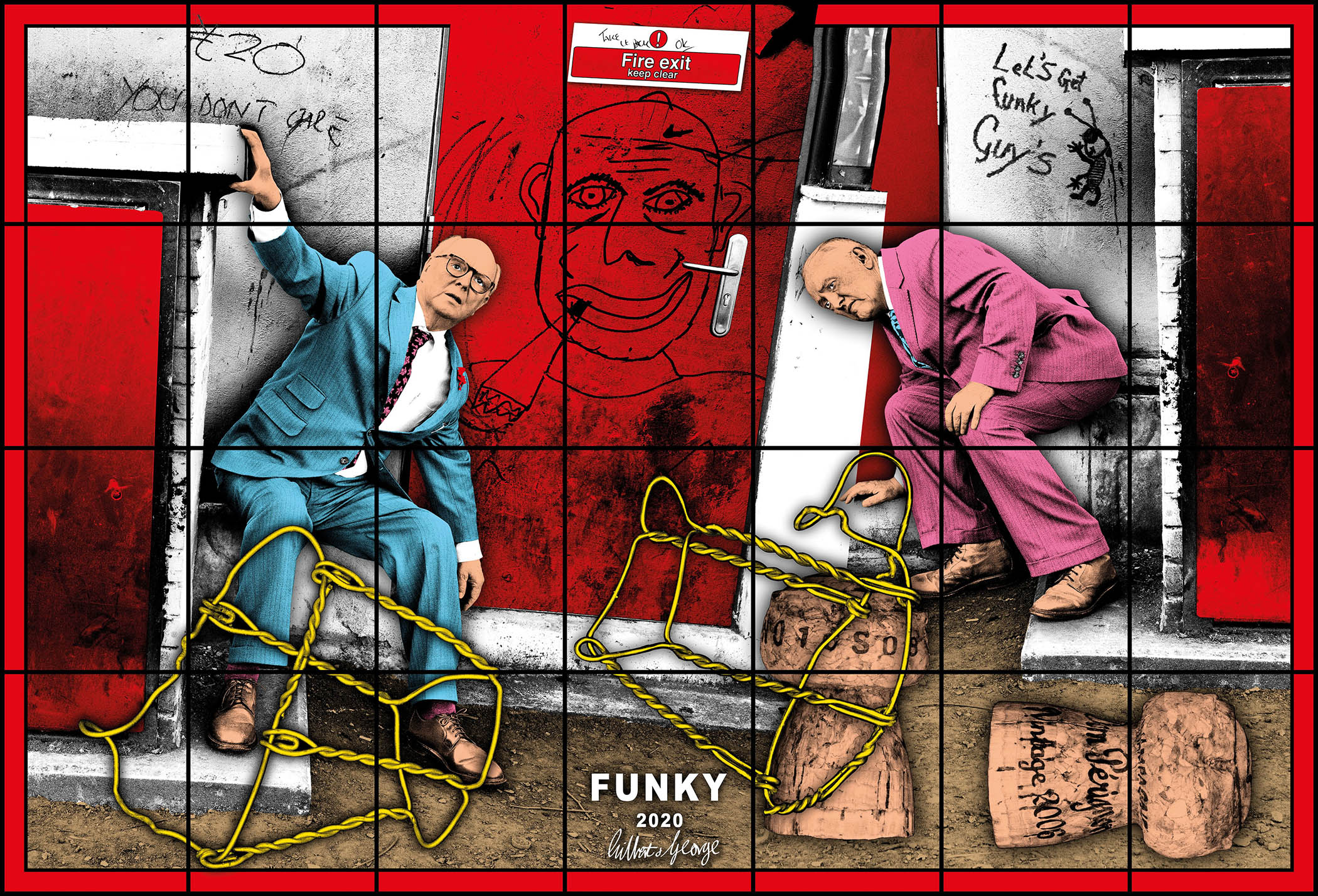

The studio is expansive. Roughly 25 years ago, Gilbert and George upgraded from analogue printmaking equipment to large digital printers. They aren’t luddites. Their works are designed on a computer before being printed out in large grids, square by square. The images mostly begin with photographs, which are scanned and digitised. Resultant artworks often feature detritus from the street, rude words scribbled on urban surfaces, even the pair’s own blood, sweat, tears and semen, magnified into decorative abstraction. As a rule, pieces contain images of the artists themselves. They also have titles – usually something impolite. Piled folders are variously labelled Free Dick, Kiss Me (Black) and “Fuck ’em All”. A typical Gilbert and George is boldly coloured in trademark yellows, reds and blues, resembling stained glass.

It’s rare to know exactly how your interviewees will dress before you even show up, but Gilbert and George are not your usual interviewees. In the almost 60 years they’ve worked together, they’ve in effect become one person – or as they like to say: “Two people, one artist.” They dress the same: always in suits. Today, they’re in Donegal tweed from a Tibetan tailor in Clerkenwell. “We use the same tailor until they either retire or die,” George says with pride. “A Tibetan tailor! Isn’t that marvellous; how multicultural.”

As a rule, Gilbert and George works, such as Funky 2020, contain images of the artists themselves

Gilbert and George have done dozens of interviews over the years and often repeat stock phrases. If a journalist asks whether they argue, they’ll respond: “We call that the great heterosexual question.” If another wonders what happens if one of them disappears under a passing car, they’re met with: “Never fear – we always cross the road together.” Germaine Greer once wrote scathingly that the only way they could complete their work was by “dying in unison”.

The pair do everything as one and have done so pretty much since the 25 September 1967, when they met at St Martin’s School of Art and fell in love. They are not religious. In fact, they scorn religion (though George’s brother, Alec, is a vicar). However, they still maintain an almost divine interpretation of that first encounter. “It’s all part of some great mixed-up scheme,” George says of that moment. “We’re not entirely in control of everything.” They often equate their relationship to a kind of cloud that gathered around them. Gilbert recalls that George, who was born in Plymouth, was the only person who could understand his English. Gilbert grew up in South Tyrol, northern Italy, speaking Ladin, a language native to the Dolomites.

Their routine is rigid. It’s evolved so that they can think about art as much as possible. They wake at seven o’clock, work until 11am or so, then go for lunch at a local cafe, Nilly’s. Sometimes they walk in near-perfect unison; sometimes they make the 500-metre journey by cab. After that, they work until 6pm, watch the news, then set off to dinner at Mangal 1 in Dalston. Always Mangal 1. They used to go to Mangal II, but that restaurant started playing music. Usually, they order lamb chops. The pair used to watch TV after dinner – Midsomer Murders, then Heartbeat – but nowadays they’re straight to bed. Then the same again the next day. They also dream, you would imagine, together.

The conjoinedness of Gilbert and George is perhaps the best thing about them. It’s genuinely affirming to know that two people can live and work in such prolonged, intimate proximity. They do seem to love each other. However, they are different. “Gilbert is nice and quiet,” says the proprietor of their local cafe, “but George wants to talk with everyone. When he sees someone handsome, he’ll go up and talk to him.” George enjoys lewdness and flirtation. After our interview concludes, he bemoans the fact that I’m not wearing jean shorts like Suki, our photographer. “Kiss, cross, screw!” he says at one point, reading out one of their works, before gleefully asking me: “Have you tried that?”

When I was at art school at Goldsmiths in London 10 years ago, I don’t remember Gilbert and George being seen as particularly relevant or cool. This was probably in part due to George’s long-professed affection for the Tory party (he claimed to admire David Cameron and George Osborne, as well as Margaret Thatcher).

“They just seem like Reform pub bores now,” one of my former tutors says of their output, “churning out the same stuff decade after decade, with their Jacob Rees-Mogg line in being willing to offend Guardian readers.” (Famously, Goldsmiths tutors don’t mince words.)

It might also have been that the artists’ desire to shock occasionally borders on the crudely offensive. One work from 1986 – the year they won the Turner prize – was titled Paki, which George defended, saying: “There’s nothing wrong with the word; it’s the same as ‘Aussie’ or ‘Brit.’”

Today’s art students also may point out that these two boomers had the privilege of becoming artists during a gilded age for art creation, when rents were low and social provisions were strong. They seem oblivious to the deterioration of those conditions. “We’ve been very lucky that we’re part of a very successful, optimistic part of history,” they tell me. When I ask if they’re aware that young working-class artists can’t afford to live in London, let alone make work, Gilbert says: “No, but I don’t believe it.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The interesting thing about Gilbert and George is that they are both simultaneously not in the world, and a lasting facet of the local community (not that they like the term “community” being applied to them; “We are part of it in our own way; we’re not going to dinner parties,” Gilbert explains). The artists, for all their besuited conservatism, have long said that they are driven by a shared sense of purpose to bring art to everyday people. They pride themselves in offering “art for all” and being “lower class”. In 2023, to the delight of local businesses, they opened the Gilbert & George Centre, which is free to enter so that works of art (which is to say, their art) can be available to everyone.

They excitedly evangelise about the reach of their forthcoming show and about how many working-class people will be attending. However, when I ask whether the exhibition is free, they’re shocked to find that it isn’t, and even more shocked to find that an adult entry ticket is £20. “My God!” Gilbert says, as far as I can tell, completely sincerely. “That’s quite expensive.” (The Hayward has since been in touch to reassure me that it offers concessions, including for Lambeth residents, under-30s and recipients of universal credit.)

The duo’s artistic journey can be traced back to an afternoon in 1968, when they were on the roof of St Martin’s, holding sculptures, gazing out over Soho. Suddenly, they realised they never had to hold sculptures at all; that they could become “living sculptures” or, as Gilbert puts it, they could “be the apple”. They’re eager to impress that this was totally new and a departure from previous experiments in performance art. “We were not performers; we are ‘it’,” Gilbert asserts. “We are always; we are not doing a performance … Gilbert and George are the living sculptures for ever.” After that, their life became their art; a fate that sounds nightmarish, but that they appear to relish.

I ask what separates their living sculpture revelation from the output of, say, Yoko Ono, who objectified herself in works such as Cut Piece (1964), where audience members were invited to cut away sections of her clothes. “She’s a damn fool Japanese and we’re not – that’s the difference,” says George.

Gilbert and George’s living sculptures were anointed at the Rolling Stones’ 1969 Hyde Park festival gig. The pair put on metallic face paint and walked meticulously through the crowd, passing ecstatic free-lovers (masturbating, knees up, under their kaftans, George likes to recall). A lot has been said about the deliberateness of their walking. It had a profound effect on the Rolling Stones’ fans, who rushed towards them, posing deep questions. “They thought we had some secret to life.”

Things really kicked off with eight words from a young man at a London exhibition that same year: “You do something in Düsseldorf with me, huh?” That man turned out to be the German art dealer Konrad Fischer. That was when Gilbert and George started singing. They would paint themselves, stand on a table and perform eight-hour renditions of Flanagan and Allen’s music hall standard Underneath the Arches, a record they’d discovered in a second hand shop.

The song had a profound effect on the pair, just as it did on the American art dealer Ileana Sonnabend, who saw their The Singing Sculpture in Brussels and invited them to New York. And that was it. They had made it. They had “won”, as they’re fond of putting it. Both can still recite the song from memory, and do exactly that, bursting into a rendition for me right there at the table. It seems to transport them somewhere else, though I couldn’t say where.

“Back to back we’re sleeping / Tired out and worn / Sorry when the daylight comes creeping heralding the dawn / Sleeping when it’s raining / And sleeping when it’s fine / Trains rattling by above / Pavement is our pillow / Without a sheet we’ll lay / Underneath the arches / We dream our dreams away”

Gilbert and George often claim to be outsiders, or “inside outers”. “We never were in the art world,” they said in The Observer four years ago. “We never wanted to eat lasagne in other people’s houses.” What this means is unclear but they put part of this separation down to their politics. “The art world is based on a myth of being radical and extreme, nutty and leftwing,” says George, “It’s more interesting to be different from that.”

The art world is based on a myth of being radical and leftwing. It’s more interesting to be different

The art world is based on a myth of being radical and leftwing. It’s more interesting to be different

And that’s the thing about Gilbert and George’s conservatism, or rather George’s conservatism (Gilbert has never voted): it feels more of an accessory, a way of standing out – like their matching suits. They don’t seem interested in actual politics. When I mention the rise of the far right, they respond with the detachment of two badgers receiving a parking ticket. “We don’t know anything about it,” Gilbert says.

They do not think of themselves as above society, but they act removed from it. They don’t look at other artists’ work, as they don’t want to be “contaminated”. However, they are regularly taken by the world around them, by what they call the “living experience”. When I ask what inspires their work, Gilbert answers straight away.

“George …”

I assume he’s talking about the obvious George. But then he clarifies.

“George, who is not here any more – the other George, who is nearly dead.”

I’m confused.

“George Crompton,” he says.

I still have no idea who that is.

As it turns out, the George in question – the other George – was a homeless person who used to sit with his friend Tara outside this house. Sometimes they’d sing songs together. (Crompton died at the nearby St Joseph’s hospice between this interview and its publication.) Crompton was from County Durham. He’d come and sit in the corner of the studio while Gilbert and George worked. When they had to switch the lights off for the enlarger, Crompton would sit contentedly in the dark with them.

He became their friend. On the studio wall, there’s a picture of Crompton, smiling in front of a cake with “Happy 50th birthday” written in icing. Both Tara and Crompton were well liked by the community. Tara died last year. Recently, the artists found George outside their house, bleeding, and called an ambulance for him.

I don’t hear of other such friends but Gilbert and George are not as isolated as they might seem. Things speak to them: the street speaks to them, the homeless people speak to them (when they moved in, the street was full of down-and-outs, often traumatised from the war), the landscape of the East End speaks to them. Death speaks to them too.

“You’d be a damn fool to ignore that,” George says of death. “We’re surrounded by dying people and funerals … every newspaper has an obituary column.”

“All our teachers, all our gallery directors,” Gilbert chimes in. “All dead.”

I ask if their understanding of death has changed as they’ve grown older.

“I don’t have a problem,” Gilbert replies with a smile. “Whenever I drop, I drop. Don’t you think, George?” He agrees. The artists might not be concerned with their own deaths, but they are concerned by their legacy, which they term their “legover”. The Gilbert & George Centre, which contains an exhaustive archive of their work, impresses them on to the local landscape. It’s as much a pyramid as a museum. Anyway, it’s all in the service of winning. Gilbert and George want to win. “He did it all wrong – but he won,” George says of Van Gogh.

“Have you won?” I ask.

“So far so good … No artist of our generation did what we did,” George concludes. Then Gilbert explains: “We’ve found a language that is ours. That’s quite exciting.”

Gilbert & George: 21st Century Pictures is at the Hayward Gallery, Southbank Centre, London, from 7 October to 11 January