The flags of Georges Seurat (1859-91) freeze mid-flutter against an opalescent sky. Clouds hang motionless, tinged oyster and pink. The channel of Gravelines, near Dunkirk, where Seurat spent the last summer of his tragically short life, is as luminescent as limelight, calm and still, yet conspicuously composed of teeming dots.

Everyone knows the technique: the little dabs of complementary colours that lie next to each other, coalescing into a new radiance in our eyes. The rules were rigid, but painting would henceforth be changed. The French chemist Chevreul’s famous colour wheel is reproduced at the entrance to this show, so that you can see for yourself how each of his 72 hues behaves in relation to all the others. Then you might notice the way lemon next to violet creates a halo, in the art, how cobalt sharpens orange. Or maybe not. The science was never of any interest compared with the paintings.

Which is why the National Gallery’s first show in the reopened Sainsbury Wing is so surprising. The paintings are often outstandingly beautiful – Paul Signac’s limpid coastlines, Camille Pissarro’s late-afternoon meadow, two of Seurat’s most mysterious oil sketches, as well as several larger paintings – but the curators have gone further and wider. They present pointillism as a pan-European movement, with extraordinary aims and variations for such a narrowly doctrinaire style.

‘Hysteria strictly repressed’: Georges Seurat’s controversial Le Chahut, 1889-90, bought by Helene Kröller-Müller in 1922

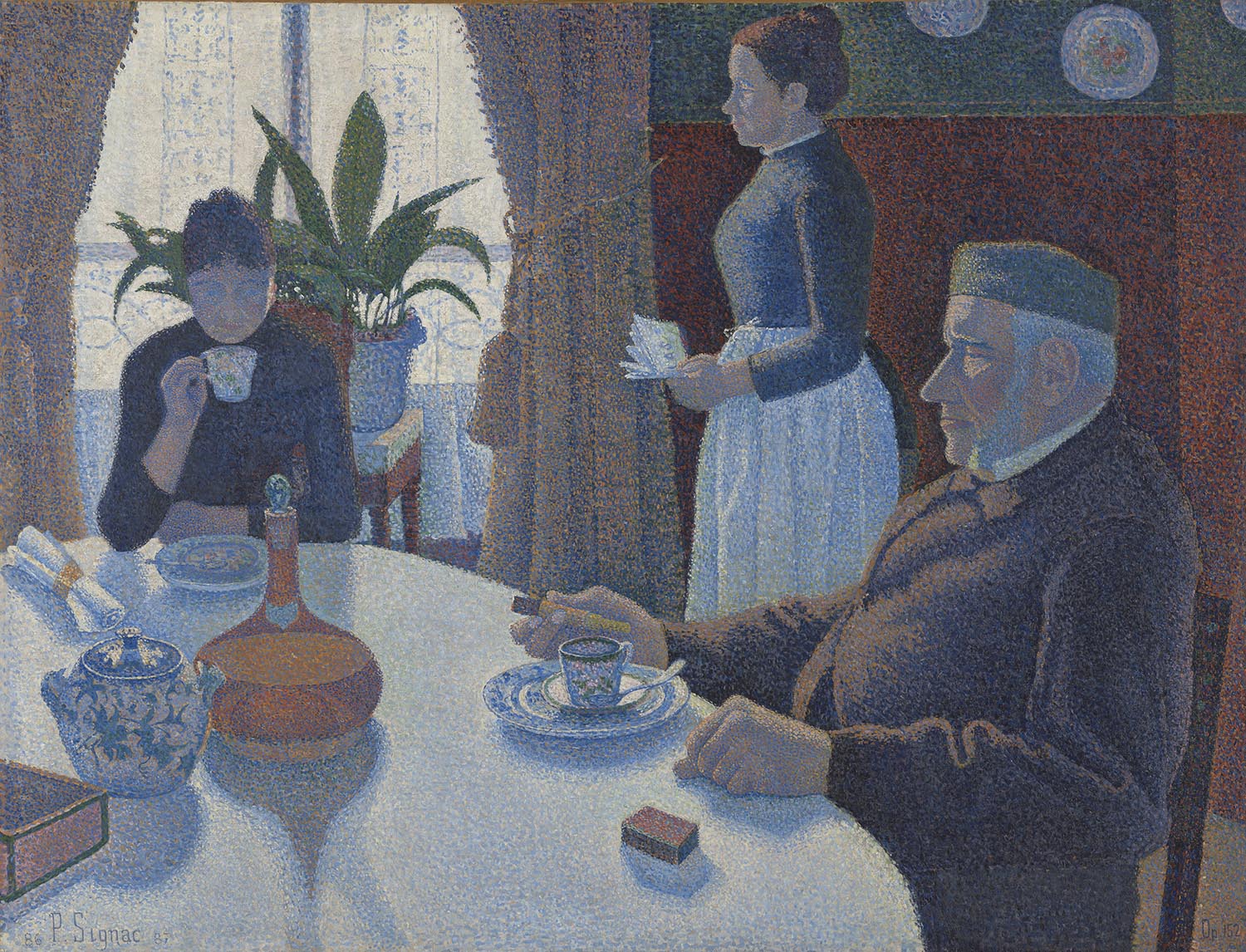

Signac meets Seurat in Paris in 1884 and becomes his instant apostle. But Signac’s dots are slightly larger, his art therefore a touch coarser. Sometimes he resorts to traditional brushstrokes and even falls back on the occasional line to describe a fence or a flagpole. But very soon his dots turn political. In his 1867 work The Dining Room, husband, wife and anxious maid are separate and silent, isolated like chess pieces on a board, the stiff bourgeoisie at its Sunday table.

The Belgian artist Théo van Rysselberghe sees Seurat’s La Grande Jatte in 1886 at the eighth impressionist exhibition in Paris. Purple pollution drifts sideways in Van Rysselberghe’s port of Boulogne, which looks like a Monet crossed with a Seurat. Smog thickens over glowering London factories by his compatriot Georges Lemmen, also struck by the atmospheric effects of heavy industry. Many of the pointillists were anarchists, putting their avant-garde style to visions of a better future. Signac shows himself plucking figs with his family, trousers rolled up, a shovel at his feet, in some vague Mediterranean fantasia.

Georges Seurat’s Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp, 1885

Seurat’s technique could be carefully emulated, if never equalled. It is put to mawkish uses by the Dutch painter Jan Toorop, with his two-painting sequence Evening (Before the Strike) and Morning (After the Strike). In the first scene, before the brutal suppression to come, the worker’s wife is full of anxiety, her face alas resembling a blue rash. In the second, her husband’s murdered corpse is being carried away by a man and boy. It is nearly impossible to make out the body, however, in the blizzard of dots.

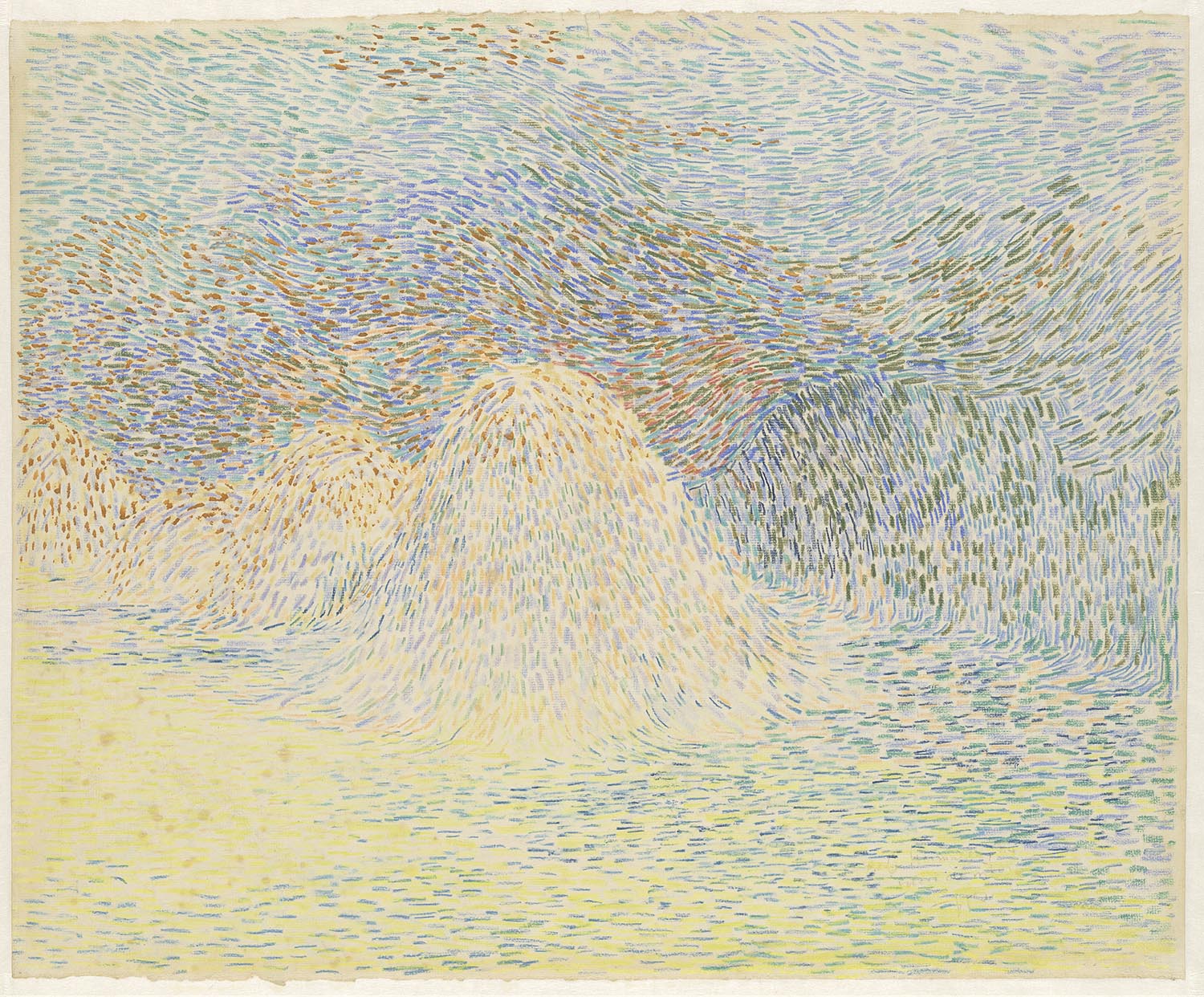

There are artists here whose work has barely been shown in the UK before. The Belgian painter Anna Boch uses the dots to soften her scene of a Sunday morning service where the rural church is so small that the congregants are praying outside, heads bowed in the gentle sunlight. Pointillism is ideal for separating people and shapes in circumambient light. The implausibly named Johan Aarts and Johan Thorn Prikker depict dunes and haystacks and noonday sun in their native Netherlands with a combination of extreme precision – the dots – and lyrical romanticism – the glowing colours. Prikker worked in pastel on paper, and what you see is something like the deconstruction of a landscape into shape, form and abstracted mark happening at the same time in the art of his compatriot Mondrian.

Johan Thorn Prikker’s Basse Hermalle, Sun at Noon, 1904: ‘extreme precision and lyrical romanticism’

It is remarkable to think of a woman in high-necked Edwardian dresses buying art as modern as this in 1912. Helene Kröller-Müller hung her major collection in plain wooden frames on white walls, what is more, and eventually gave it to the Dutch state, along with the museum that takes her name at Otterloo, near Arnhem. It is perhaps no coincidence that the National Galley is paying tribute to Kröller-Müller in the very week it announces that it is lifting its own ban on showing art painted after 1900.

She bought Seurat’s controversial Chahut in 1922, and we see it here for the first time, alongside other loans from her museum. A line of cancan dancers high-kicking it in electric light and raging music, it feels like hysteria strictly repressed. The smaller studies that surround it in this exquisitely airy presentation are far more entrancing: a single figure on a bank, disappearing into the green distance; the strange nocturnal light of Seurat’s black conté-crayon sketches, where figures arrive through an atmosphere of complete mystery on to the fine-grained paper.

Pointillism, or neo-impressionism as they preferred to call it, dissolves away fast. Signac was a loyalist, but most artists shifted style, having stretched the rules as far as they could. Seurat, though, is unique: his dots allow for slowness, mastery and control. A kind of serenity enters in, poised as a Piero. Each scene is only a picture – as Seurat’s painted borders tell you, if not the dots – yet each bewitches and stills you.

Radical Harmony: Helene Kröller-Müller’s Neo-Impressionists runs at the National Gallery until 8 February 2026

Photographs courtesy of Collection Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy