In Jean Rhys’s 1931 novel After Leaving Mr Mackenzie, the protagonist, Julia, is telling a stranger how she once worked as an artist’s model for a sculptor named Ruth. While she sat for Ruth, she talked about her life. “And all the time I talked I was looking at a rum picture she had on the wall – a reproduction of a picture by a man called Modigliani. Have you ever heard of him? This picture is of a woman lying on a couch, a woman with a lovely, lovely body. Oh, utterly lovely. Anyhow, I thought so. A sort of proud body, like an utterly lovely proud animal. And a face like a mask, a long, dark face, and very big eyes. The eyes were blank, like a mask, but when you had looked at it a bit it was as if you were looking at a real woman, a live woman.”

Rhys’s protagonists are lonely, penniless women who live transitory lives in crowded cities and turn to men for money and companionship, only to be abandoned: an archetype that became known as “the Rhys woman”. As the writer Mary Cantwell put it, they are women who “struggle with life the way a sleeper struggles with a tangled blanket.” These characters are interested and invested in appearances: masks, reflections, clothes, mannequins, portraits, makeup and mirrors are repeating motifs throughout Rhys’s novels and short stories. And though Rhys went through life feeling as if she were “a person at a masked ball without a mask”, she is – in interviews, biography and her own memoir, tellingly called Smile, Please – somehow unknowable, always glimpsed through a veil.

Postures: Jean Rhys in the Modern World is an exhibition curated by the Pulitzer prize-winning critic and essayist Hilton Als, “a kind of portrait of the artist through art”. Held at the Michael Werner gallery in London’s Mayfair, it attempts to capture something of Rhys’s work and life in a series of contemporary artworks – Kara Walker, Sarah Lucas, Hans Bellmer, Celia Paul and Leon Kossoff all feature. It is, aptly, dynamic, unsettling, irrepressible. There are portraits of fearless, enigmatic women, landscapes heavy with dark shadows, twisted sculptural bodies, and eyes that seem to look back.

Walking round the show with me last week, Als explained how he first encountered Rhys’s fiction when he was 15. “I remember being so amazed, first by the language: this was an incredible poet who was writing so brilliantly about ... about immigration, really. She had this relationship to being displaced that I felt spiritually, but I also know I wasn’t old enough to understand. I just hadn’t lived long enough.”

Jean Rhys moved to England after growing up in Dominica

Five years later, in 1980, Derek Walcott’s poem named after the author was published in the New Yorker, in which the St Lucian Nobel prize winner imagines Rhys’s childhood in Dominica as glimpsed through an old, mottling photograph. Als was 20 years old, and was “blown away by this act of empathy”. Reading Walcott, Jamaica Kincaid and Caryl Phillips, he realised that “a lot of the West Indian writers I was reading had a relationship to her in some way”. He read her short stories I Used to Live Here Once and Let Them Call It Jazz with a new level of understanding. “My life began to catch up to Jean Rhys,” he says.

Rhys was born Ella Gwendoline Rees Williams in Dominica in 1890. Her parents were William Rees Williams, a Welsh doctor, and Minna Lockhart, a white Creole woman descended from a Scottish family who had been on the island for three generations, inhabiting a slave-owning sugar plantation. Gwen, as she was known to her family, loved Dominica, but felt separate from it, as she was taunted by her peers, who called her a “white cockroach”. She was lonely from a young age – distant even from herself. Smile, Please begins with an account of having her photo taken as a girl: she remembers the photographer disappearing behind a dark cloth. Then she recalls looking at the same photo three years later, no longer the same girl. “The eyes were a stranger’s eyes,” she writes. “It was the first time I was aware of time, change, and the longing for the past. I was nine years of age.”

At 16, Rhys moved to England, but was mocked there for her Caribbean accent – not helped by the fact that she and her schoolmates were studying Jane Eyre, and Bertha Mason, the “madwoman in the attic”, was a white Creole. Her accent also frustrated her attempts, in her early twenties, to become an actress. To cope with her alienation, she turned to drink and, more significantly, writing. After marrying a Dutch writer and moving to Vienna, Rhys met Ford Madox Ford, who would become her lover and literary mentor. She began writing short stories and a run of modernist novels: Quartet (1928), After Leaving Mr Mackenzie (1931), Voyage in the Dark (1934) and Good Morning, Midnight (1939). Her next novel would not be published until 1966, but it proved to be her masterwork. Wide Sargasso Sea is a prequel to and retelling of Jane Eyre from the perspective of Bertha (or, as she was known as a child, Antoinette).

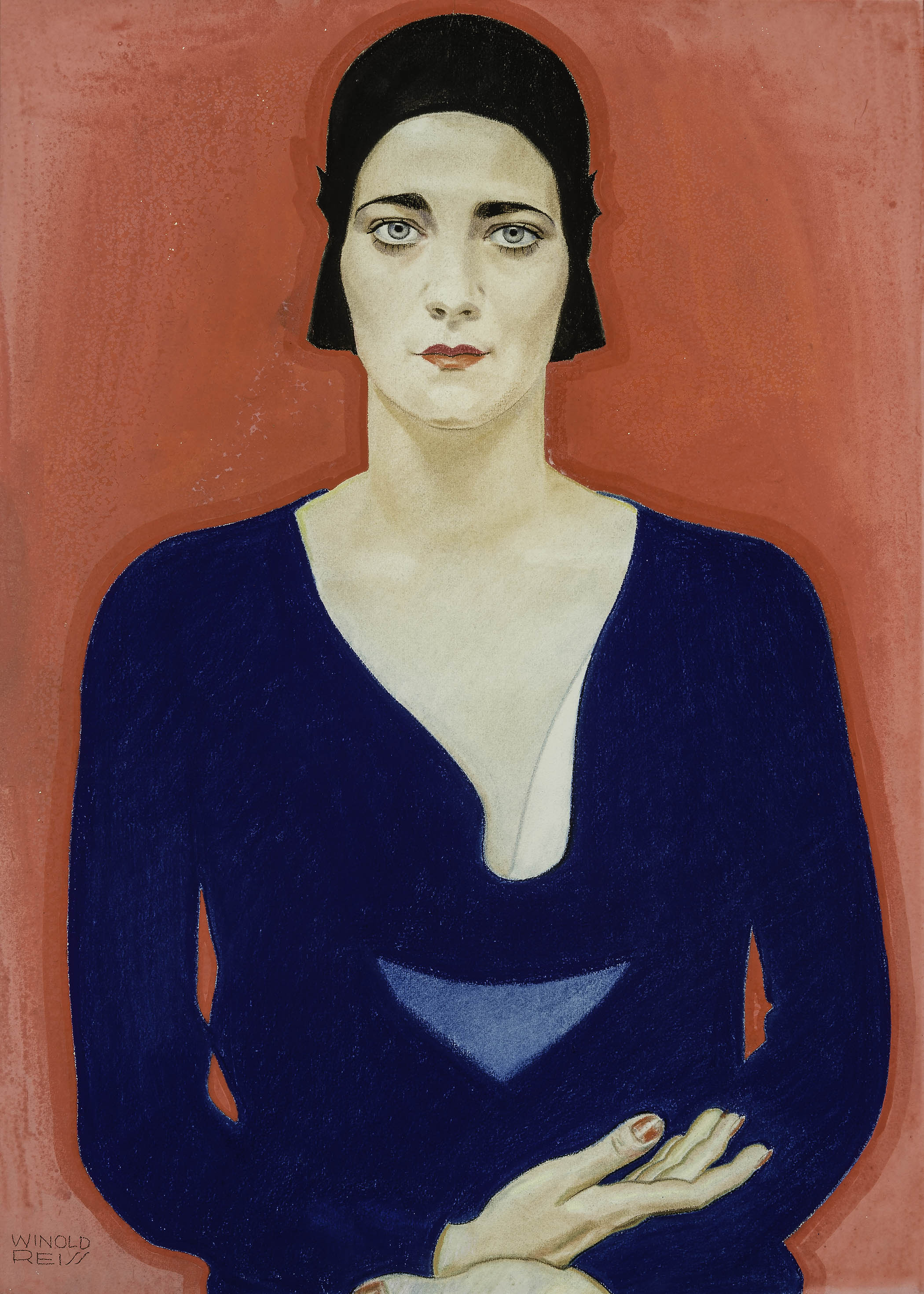

‘As if you were looking at a real woman’: Winold Reiss’s portrait of Katherine Hamill

“She is an accurate recorder of the complications and the ways in which you [as a Creole person ] don’t fall on either side,” Als told me. “She couldn’t belong to the black world, and she didn’t belong to the white class. I think it’s more about class, actually: in her society, she couldn’t belong to the class that she was supposed to belong to.” He suggests that this is what attracted writers such as Walcott, Kincaid and Phillips. “She was writing a kind of English that was a combination of sounds: the sound of her home, the sound of empire, the sound of reading.”

In this exhibition, Als hopes to channel the qualities in Rhys’s written work into the visual realm. Each room contains quotes from Rhys’s novels and memoirs that complement the works on show. Did he try to look at the art as if he were seeing it through her eyes?

“Definitely… The life that Jean Rhys brings to the page had to be in the visual work as well. The visuals had to be equal to the energy and the mystery of Jean Rhys.”

The first artist that came to mind when Als was conceiving the exhibition was the Indian-born British painter Celia Paul. “I remembered Celia Paul had done some work on the Brontës. The ghost of the Brontës was a significant starting point for me. Rhys had been so haunted by [Jane Eyre] for many years, and then to take just a few pages of melodrama and create a whole novel. Wow. That was amazing to me.”

Paul’s painting of Charlotte Brontë sits in the first room of the exhibition; it is a dark, spirited portrait of thick brushwork. Brontë looks away from the viewer almost defiantly, her blue eyes fiery and wild.

This room, themed around Rhys’s childhood in Dominica, also contains two more of the most striking works in the exhibition. Hurvin Anderson’s large-scale untitled painting – red hot flames, grey smoke and black clouds on a backdrop of deep yet lurid green – is one of the only works directly responding to Rhys’s writing. Anderson depicts the scene in which the young Antoinette watches as her home on a sugar plantation in Jamaica is burned down by formerly enslaved people: “The house was burning, the yellow-red sky was like sunset and I knew that I would never see Coulibri again.” A ledger of numbers on the left of the picture corresponds to catalogues of slaves.

Kara Walker’s West Indies depicts the violence of slave labour

“What I love is how the picture moves up vertically,” Als says, “and that the smoke is as dense as the cloudscapes, the landscape as this overwhelming presence.”

On the opposite wall, Kara Walker’s West Indies – produced in 2014, when she was making her giant, provocative sugar sculptures – depicts the violence of slave labour-fuelled sugar production in the region: dark cartoonish outlines of palm trees, enslaved workers and slaveholders stand out against a sea of blood-red watercolour. “I wanted to have Hurvin and Kara in the same room. They’re talking about similar things, but in very different ways.”

A second room responds to Rhys’s time in Europe – London, Paris, Vienna – and the Rhys women of her novels. There are Eugene Atget’s photographs of sex workers, heads held high, staring down the lens. There’s Winold Reiss’s portrait of a woman called Katherine Hamill – dark hair bobbed, red bow lips, blue deep-cut dress, and still, grey eyes. I think of Rhys’s Modigliani: “The eyes were blank, like a mask, but when you looked at it a bit it was as if you were looking at a real woman.”

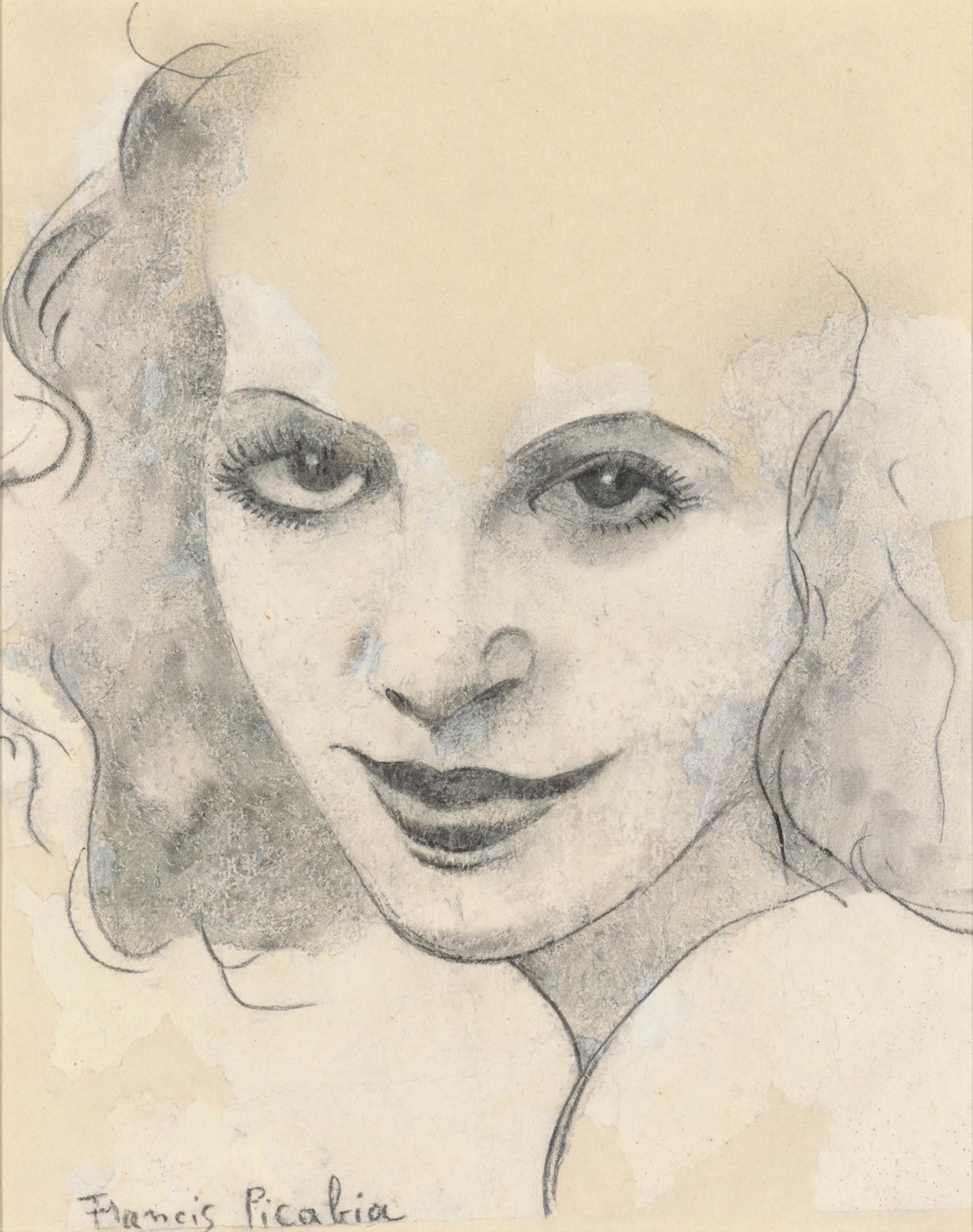

“I wanted to have that deco look associated with Rhys,” Als said. The Rhys look is unmistakably present in Francis Picabia’s two works titled Tête de femme – part of his drawings of real and imaginary women of the 30s and 40s. One of Bellmer’s subversive doll photographs sits alongside a Lucas sculpture of a pale, knotted body. It’s barely possible to discern an abstracted human form in the lumpy surfaces and rusty palette of Eugène Leroy’s impasto oil painting Visage gris avec lumière.

That work has a parallel in the third room, which concerns Rhys’s time in rural England, having returned from a brief trip back to Dominica in her mid-forties. “She was becoming a different kind of artist,” says Als. “All of the works that you see here are related to this kind of modernism that she was inventing, [while also] living in the legacy of her world, and the history of colonialism.”

The ‘Rhys look’ in Francis Picabia’s Tête de femme

In Leon Kossoff’s mighty Seated Nude No. 1, swirling lines of paint whirl and eddy to create a shape that is both human and topographical. “This room is really about the landscapes,” Als says, “and it’s also about the landscape of the body. We have these relationships to place and to the body that we can’t really escape.” A distorted landscape by Reggie Burrows Hodges drips into abstraction, acidic pink, arsenic green, and deep black. “He wanted to do something about Rhys that was not only about the return to Dominica, but about disillusion of memory: how you go to a place that you remember and think is yours, but it’s quickly evaporating.” A floral dress owned by Rhys stands in the middle of the room – you can’t help but notice how small she was – and shares Hodges’s palette of blacks and pinks.

The final room contains photographs of Walcott, Kincaid and Phillips, and an evocative series of 35mm slide photos of Dominican life. Black Dominicans work, rest and look after children wearing long white Edwardian dresses, staring down the camera with a fixed gaze. It’s a window into another world. There are 69 photos in total, and I stand and watch them all flicker in and out of life. They take the viewer to the world of Rhys’s early teenage years perhaps more immersively than her writings.

In both Dominica and in England, Rhys “couldn’t fit,” Als tells me. “And when you don’t fit, I tend to trust your view more than if you have a longing to fit. I think that Rhys’s work is defined by a certain enormous sense of longing, but at the same time, never belonging.” The exhibition both captures and, thankfully, fails to capture Rhys: the works reflect the mystery of her presence more than they elucidate.

In After Leaving Mr Mackenzie, Rhys’s protagonist Julia continues to reflect on the Modigliani painting and her conversations with the sculptor, who fails to really see her. “I felt as if the woman in the picture were laughing at me and saying: I am more real than you. But at the same time I am you. I am all that matters of you. And I felt as if all my life and all myself were floating away from me like smoke and there was nothing to lay hold of – nothing.”

Postures: Jean Rhys In the Modern World runs at the Michael Werner gallery, London, until 22 November

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Photographs courtesy of Hilton Als and Michael Werner Gallery/The Estate of Francis Picabia/Hurvin Anderson/Kara Walker, Sikkema Malloy Jenkins, and Sprüth Magers/The Estate of Winold Reiss