Three gossips on a balcony are all side-eye and sneer. One woman points an insinuating finger at the other, while a middleman waits hungrily for her response. Razored eyebrows and savage kiss curls, racy greed and scandal: this is the fag end of the 1920s, with additional barb.

Edward Burra (1905-76) paints these vicious scenes everywhere. Barflies ogle girls in see-through dresses while the teashop staff wend their way naked among gawping customers. Cinzano fuels the sailors of Marseille, the ship awaiting their tipsy return in the dock outside. Eyeshadow and lengthening stubble are the same caustic blue; even the lino and hissing urns appear meanly collusive. Sharp little teeth are Burra’s subject, but also his manner.

As a sickly youth who endured anaemia and rheumatoid arthritis from childhood, his energy seems to have come from watching (and listening: there are many syncopated jazz scenes). His first style, after art college in London, conflates elements of tubism and surrealism with sardonic George Grosz.

Burra finds Grosz’s Berlin, in all its seedy Weimar decadence, from New York to Toulon and Rye. In fact everything appears to remind him of Sussex, where he lived. From Cape Cod he wrote home: “It’s Hastings, really.”

That’s apparent, to a fault, for most of this exhaustive exhibition. All scenarios have equal tone and weight. It might be shifty nightclub transactions in Harlem, flamenco dancers in Spanish bars or vaudeville performers taking tea in London: all are equally stylised, mannered, derisive.

‘Razored eyebrows and savage kiss curls’: Balcony, Toulon, 1929 by Edward Burra

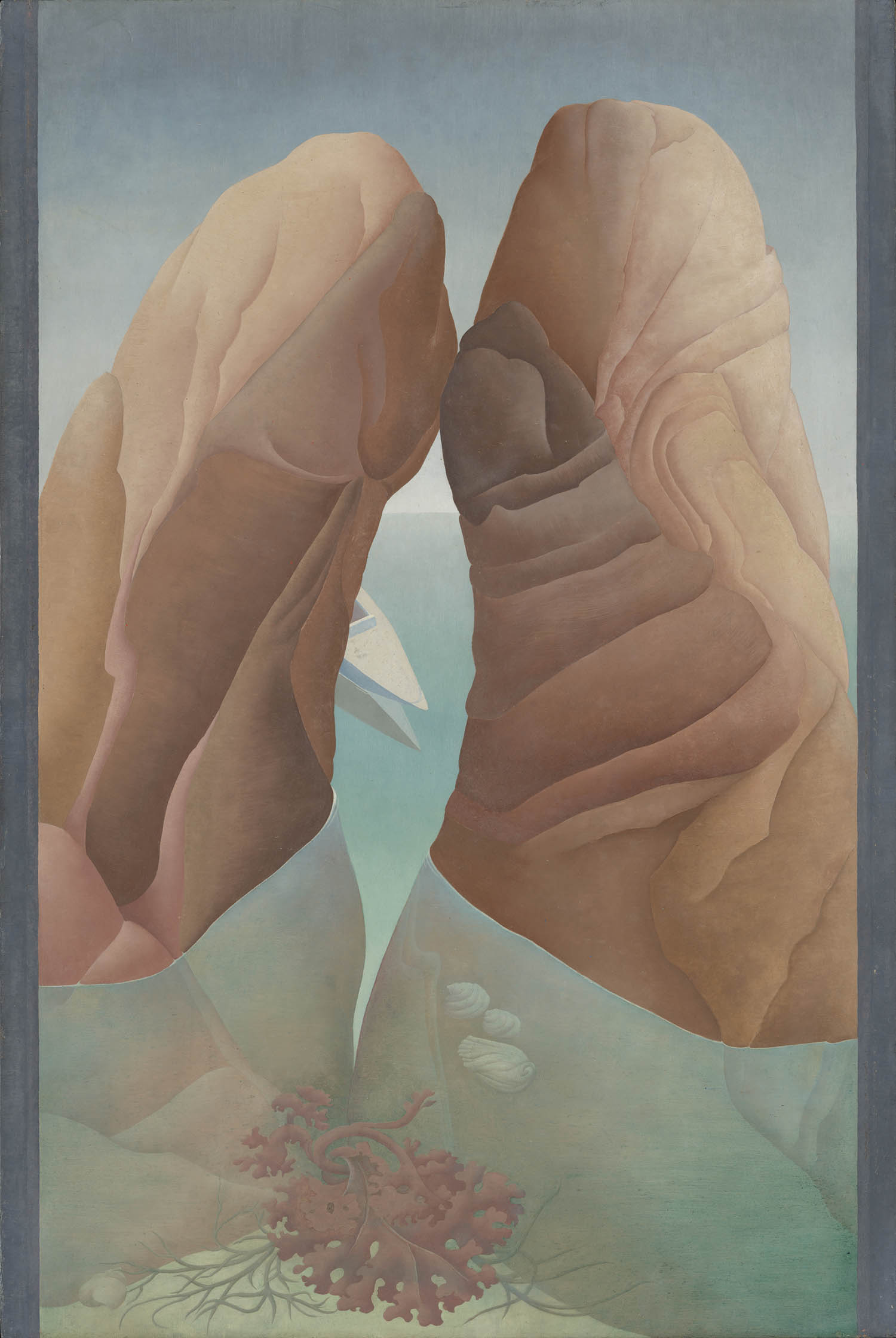

Double take: Scylla (méditerranée), 1938 by Ithell Colquhoun

The men in bird-beaked masks that appear from the 30s onwards are first associated with the Spanish civil war, in which the artist initially supported Franco, and then again with the second world war. It is hard to tell one macabre, scarlet-robed figure from another in either of Burra’s wars. And while some people admire his paintings of Harlem, they also appear questionable to me: all those guys with bulgy eyes, big white smiles and innate rhythm.

I used to think that Burra disliked women, but on this showing, the jaunty vituperation is about even-handed. Are his pictures funny? The wall texts seem to think so. But gradually everything shifts. Night figures appear with sightless eyes; roads start to buckle and stretch into the distance; a hand appears so close to the picture plane it all but blocks the view of the drinker across the table.

The masterpieces are all at the show’s end: staggering watercolours of prodigious scale, showing the English landscape as it appeared to Burra from his sister’s motorcar in the 70s. Northumberland is a sequence of rhyming female forms, rising beneath ribbed green hills. Dartmoor steals away under glowering skies, attended by a congregation of watching stones. The rollercoaster road to Whitby aspires to a golden light so boundless and mysterious it might be celestial.

It is almost impossible to believe Burra could sustain this most volatile and quick-drying substance over such an expanse without a single falter, though watercolour was his lifelong medium. Asked about their meaning, he simply said: “Call in a psychiatrist.” And if there is something close to awestruck dread in these late landscapes, there is also a vision of eternity.

England, or rather Cornwall, is at the heart of Ithell Colquhoun’s outlandish art (reached through an adjoining door, with a two-for-one ticket). This equally oversized show – cradle-to-grave plus context and cuttings, the full Tate Britain menu – presents almost 150 works.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

There is no change, or range, no expressive development. As a cartoonist, Yoshitomo Nara would have been sacked years ago

There is no change, or range, no expressive development. As a cartoonist, Yoshitomo Nara would have been sacked years ago

Born in India, Colquhoun (1906-88) studied at the Slade, witnessed Dalí’s famous diving suit lecture and was photographed holding a sheaf of wheat by Man Ray, before being ostracised by the male surrealists for her occultist beliefs.

None of them, however, could surely have painted the double take of a view in Colquhoun’s most famous work. In Scylla (1938), you are either looking at the sea between two coastal cliffs, a seaweed frond drifting between them, or at a submerged female body with both knees raised. Water enters the crevice between them.

It takes a while to reach these cliffs, at Tate Britain, with many dubious paintings along the way (Judith holding up the absurdly peevish head of Holofernes, for instance). Colquhoun’s mystical views are esoteric, to say the least, and perhaps only those deep in Cornish lore will sense the currents of energy emitting from her quasi-abstract paintings of rocky landscapes or the ancient standing stones around Penwith, where she settled after the end of her marriage in the 1940s.

But the wildest works stand right out, and they are not the so-called surrealist flower paintings, by the way, which are comparatively tame. They are all to do with bodily union and love.

Androgyne is a fusion of two figures, cobalt and violet, to make not just a couple of androgynous forms but four people. It’s startling and radiant. But best of all are Colquhoun’s Blakeian Diagrams of Love. A winged blue figure flies up from a red chalice; a scarlet plant blossoms into heart-shaped flowers; eyes become breasts become flames become hearts. And even the smallest drawing – Dervish, with its whirling figure whipping up a feminine oval of rippling lines – seems to burst into living flames.

‘Baffling’: Yoshitomo Nara at the Hayward Gallery

The Japanese superstar Yoshitomo Nara (born 1959) is the oddest blip in the Hayward Gallery’s run of terrific shows under the directorship of Ralph Rugoff. Nara found fame long ago with his Hello Kitty-style drawings and paintings of winsome moppets with enormous eyes and button noses (he sculpts them too), who are counterintuitively aggressive, depressed or sly.

“Fuck You!” runs the caption under one huge-eyed urchin. “No Nukes” proclaims another. One little girl is furiously smoking, the next wants to save the whale. Nara and his characters never grow up.

There is no change, or range, no expressive development. As a cartoonist, he would have been sacked years ago. But perhaps that reliable consistency is exactly what puts Nara so squarely at the centre of the contemporary market.

It is baffling that some buyers prefer big canvases to small sketches on cardboard, as they do, since neither scale nor medium makes the slightest difference to the message. It is equally baffling, not to say irksome, to realise from his enormous display of album covers in the opening gallery that Nara’s collection of Karen Dalton, Nick Drake or Patti Smith, for instance, has had so little creative influence on his work.

What you’re supposed to say is that these cute little moppets are deceptively simple, that Nara understands the mind of a child. And perhaps he does. But this is global politics – and human emotion – cut up like food for an infant. Still, harvesting speeds are quick at the Hayward Gallery: nothing to see here.

Edward Burra and Ithell Colquhoun are on show at Tate Britain until 19 October.Yoshitomo Nara is at the Hayward Gallery until 31 August

Pictures provided by © the estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art, London, © Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans and Mark Blower