As we now better understand, flags – intended to corral us – can painfully divide. A small photograph on display in the exhibition room devoted to Rene Matić, one of the four artists shortlisted for this year’s Turner prize, shows a pub window draped with the cross of St George above a sign saying “Private party”.

The image has the succinct approach of a newspaper cartoon, but it may last longer in the mind than an accompanying recording of the pro-Palestine chant “Israel is a terrorist state” that rings out from a speaker and will surely draw strong responses this weekend as the show opens.

Almost since it began in 1984, the annual Turner prize exhibition has been a reliable object of derision for traditionalist critics and churlish commentators. At first, it was gleefully criticised for being shockingly new: the shark, the bed, the light switch. More recently – about the time it became a moving target, travelling around Britain – it has been shied at for the crime of becoming predictable.

Such criticisms are now themselves predictable. The prize jury has not stopped plugging away at themes of diversity and identity (generally, there’s a teasing withholding and revealing of identity in this show – a knowing game of hide and seek). But this year, it does so in a different context. And context, even in the realm of fine art, where self-expression rules, still matters. The wider context for this show is a world on a hair trigger, poised for seeming catastrophe. So Matić’s room, exploring the meaning of flags and unorthodox allegiances, has an urgency greater than the sum of its parts.

The immediate geographical context for this year’s exhibition is Bradford, that fallen industrial hub, now one of the most diverse cities in the UK. It has city of culture status until December and has done its best to attract attention, setting up 1,000 events, including a moorland sculpture trail and a celebration of its local talent David Hockney. The Turner prize exhibition has now taken over the grand Cartwright Hall, a gallery named after the Georgian inventor who automated the weaving process.

Reaction to the prize shortlist in April focused on the neurodiverse and refugee status of nominated artists and, although their backgrounds are not in the wall notes, these identities remain significant. An artist’s biography is increasingly scrutinised for potential partialities and vulnerabilities, and for clues to understanding the meaning of the work.

‘Colourful net, tape and ribbon cocoons bulge like piñatas’: Nnena Kalu’s ‘joyful’ sculptures hang in front of her swirling works on paper.

It’s a process of critical due diligence that speaks of a cautious moment. Matić, from Peterborough, happens to be non-binary and they have spoken of the influence of a black skinhead father as well as using art as a form of therapy (one that does not always help).

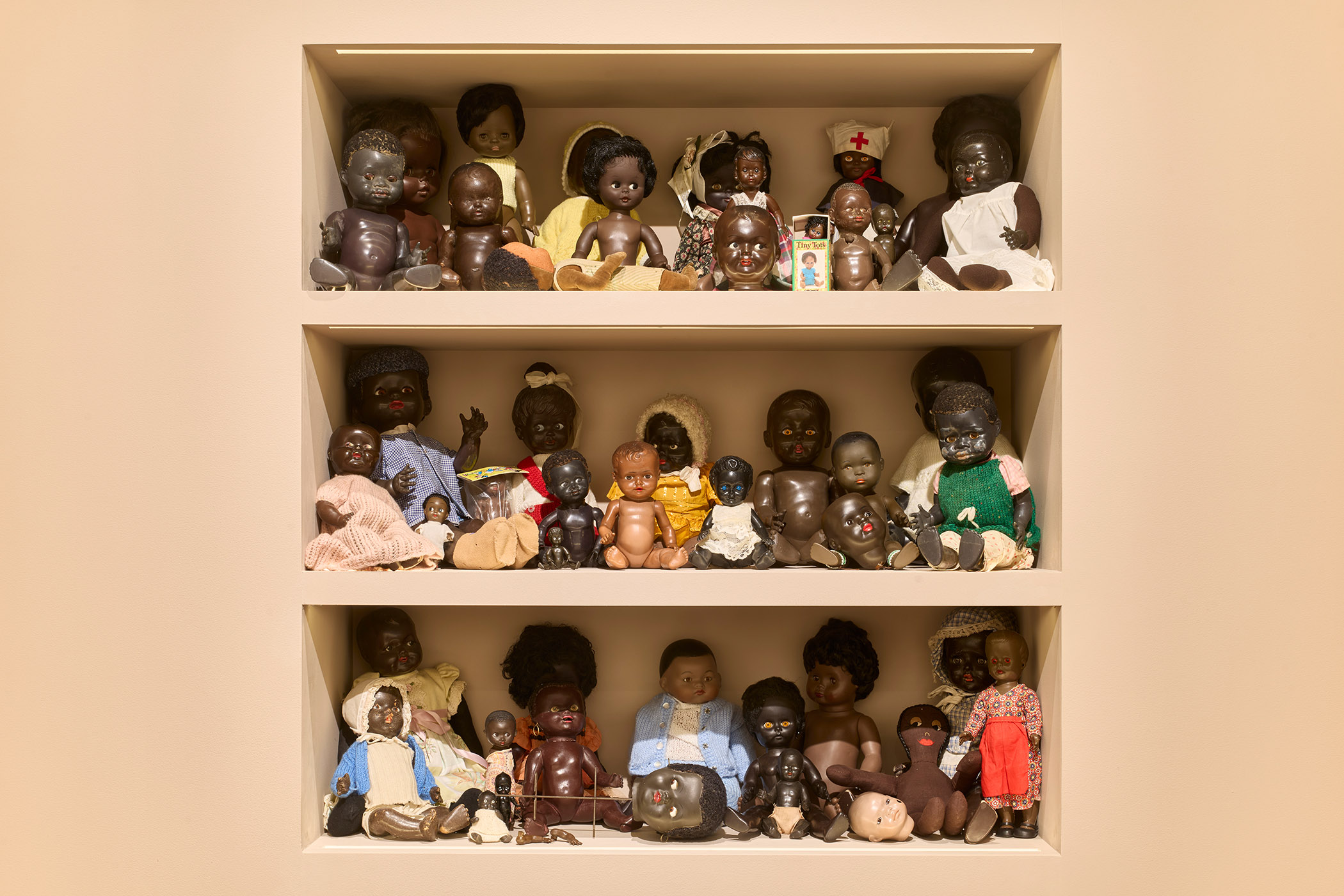

Beyond the potent use of flags, the artist has created Restoration, an unsettling display of broken black dolls, both vintage and modern. The meaning of these toys has changed in Britain, like that of the flag. Once cute colonial booty, by the 1970s such dolls were seen as “right-on”, to use a phrase that preceded both “politically correct” and “woke”. Put together now, they are dubious symbols. Their battered appeal is redolent of a “white saviour” complex and patronising attitudes towards Africa.

Mohammed Sami most recently exhibited his work inside Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire. A refugee born in Baghdad, he paints large canvases rather like menacing illustrations torn from some storybook. The Hunter’s Return lays out a foggy, swampy terrain, penetrated by laser beams. Sami’s inspiration came, we learn, from the landscapes of Bruegel and Uccello, but he has clearly also drawn on the atmospheric graphics of video games.

Next to it hangs a gentler yet more disturbing work. In Massacre (2023), he shows sunflowers trodden into the mud under the hooves of horses. What has happened here? Equally sinister is a dark, square image of shattered crockery sinking into black sludge. The artist has said he sees beauty in posing questions that we do not need to answer, and he obviously wants to avoid the cliches of a war-torn youth. Sami is surprised, he says, by the everyday things that trigger his creativity, a burden he sometimes feels is “a death penalty”.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Rene Matić’s ‘unsettling display’ of black dolls, Restoration, asks how the meaning of these toys has changed in modern Britain

The work of Nnena Kalu, a Glasgow-born artist with autism, swirls with intensity, like the insistent crayoning of a child’s first marks, but with more purpose. On paper, she makes threatening purple “twisters” and spirals that disappear down an invisible plughole. Her sculpture, in contrast, is a joyful exclamation mark in the middle of the room. Hanging from the ceiling, these colourful net, tape and ribbon cocoons bulge like piñatas and swing like Chinese dragon puppets. They call to mind the messily wrapped-up shapes found in the British artist Neil Gall’s works. One shape, draped in a mane of black tape, has the look of a stunted carousel horse. Tellingly, Kalu’s fans talk chiefly of the pleasure of watching her at work.

Mohammed Sami’s Massacre, 2023

An apt finale is a sumptuous room from Zadie Xa. A call to arms against environmental complacency, it is an immersive experience and Xa, a lapsed Catholic from Vancouver, sees herself chiefly as an installation artist. Cowrie shells and conches suspended from the ceiling pump out the sound of a sea swell, interrupted by whale music and excerpts of dystopian texts by Ursula K Le Guin.

The noise of a ticking clock and an unanswered trilling phone inject further notes of tension into the space, where light bounces on a shiny golden floor. In the centre, a mother of pearl dias sits under a three-dimensional shell, formed by shamanic bells on strings. The jury has praised Xa’s “enchanting practice”, but beneath the twinkling light, she has built a nightmare mythology for the end of times.

Each shortlisted artist receives £10,000 when the winner, who is awarded £25,000, is announced in early December. The prize, as ever, is a talent show as much as a platform and the visiting public in West Yorkshire will quietly rank these artists, ignoring the controversy of 2019, when all the nominees demanded to share the prize.

The glory of this travelling caravan of art, much like the city of culture title itself, is that it is often not the work with the most impressive set of intentions that proves most engaging.

Photographs by David Levene/Marcus Leith