Two black balloons dangle from the wall – a pendulous sausage and a dwindling pear, Adam and Eve in comic deflation. The strings from which they hang are tied in a loop above. Like a wordless speech bubble, this loop seems to joke at the odd couple below: male and female in erotic exhaustion.

This mirthful work by the great Eva Hesse is joined by another spirited sculpture: a drain cover sashaying along on well-turned legs of steel cable, like a ballerina en pointe. This is by Alice Adams (also great, comparatively unknown). And she is joined in turn by the global art star Louise Bourgeois, with any number of objects to probe and tickle the unconscious, from slumped phallic sacks to blackened bronze genitalia hanging from the ceiling like clattering bats.

All three artists appear in the Courtauld’s jubilant and exhilarating exhibition Abstract Erotic, originating in homage to an earlier show: the American critic Lucy Lippard’s momentous Eccentric Abstraction, held in New York in 1966. Bourgeois, Adams and Hesse were the only women in the exhibition. All the men, with the exception of Bruce Nauman, disappeared from sight or took a different direction.

Lippard hit on a unique strain in US art that can be seen in its purest concentration at the Courtauld. Here are three women having a wild time with lowly materials – twists of wire, papier-mache, radiator grilles, telephone leads and plastic bags, cheap latex and plaster – conjuring witty and outlandish forms. For objects so eloquent and droll, they never spell anything out. Curious jests and confrontations, these works are constantly innovative with materials and yet inflected with personal experience.

‘Wry and exquisite’: Alice Adams’s Sheath, 1964

There is a strong sense of private touch: she appears to be delving and parting the clay as if it were flesh

There is a strong sense of private touch: she appears to be delving and parting the clay as if it were flesh

Here are Hesse’s swelling hemispheres (surely her true form) tipped with whorls, or issuing delicate cords that spill in curlicues on the floor. Here are her absurdist string bags, weighed down with some nameless black matter – you reel back in disgust – or with balled-up polythene bags that gleam with a mother-of-pearl translucence (the exact opposite of dismal shopping).

Throughout there is a strong sense of private touch, especially in Bourgeois’s small-scale sculptures, where she appears to be delving and parting the clay as if it were flesh. A white plaster object, tricorn in form, conveys the strange conjunction of breasts and female torso, hinting too at the desired whiteness of Victorian bodices and skin.

Lair is a great dark mound implying something unseen within. Le Regard is a nut-shaped form opening to reveal an orb (or something more intimate) within. The associations are obvious, as always with Bourgeois, whose titles are the opposite of obscure. Her art is what you might call para-verbal.

But there is something more going on with Hesse. Her grey box, containing two nesting forms, is made of metal but incredibly soft to the imaginative touch. She courts our insatiable urge to find resemblances in art, but then she sidesteps them. And it is the same with Adams. Her wry cylinder, exquisitely crocheted out of cotton twine (she started as a weaver) stands on its own, but with a gentle spreading fringe. Small enough to hold, and so pleasingly made, it nonetheless carries teasingly intimate overtones.

Lippard’s show was formative, but most of the artists did not know each other and went their separate ways. Hesse died of brain cancer in 1970 at the age of 34. Bourgeois found colossal fame and lived to 98. Adams found none, and is still working at 94. The suggestion is that she disappeared into land art and large outdoor monuments, and perhaps that is true. But her work is the revelation of this show.

Most of it was made after the New York exhibition. There’s a stunning object reclining on a low shelf that appears nubbed and corrugated and woven all at the same time. It is coated in latex that is ageing beautifully, like golden beeswax. It could be corn on the cob, or a vast pine cone or some kind of plaited yellow hair. The curators say it weighs nothing, being only coated foam. It defies the very descriptions it courts.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

And just above it are three undulations on the wall: gauzy ripples, redoubled in twilight shadows below. It’s just three wire forms emerging out of latex, but it throws the most graceful illusions. You have to see it there, tacked to the wall with a couple of pins, to get something of the light-relief beauty of these works, made in the era of Richard Serra’s monster heavy-metal sculptures.

As Lippard herself remarks in the Courtauld catalogue, the art world has drastically altered in 60 years since her show – “far more welcoming to weirdness and yet far more market-driven”. A case in point is the YBA generation artist Jenny Saville (born 1970) whose supposed weirdness – painting female flesh, in quantity, in closeup – made her the most expensive female painter alive when her 1992 self-portrait sold for £9.5m at Sotheby’s in 2018.

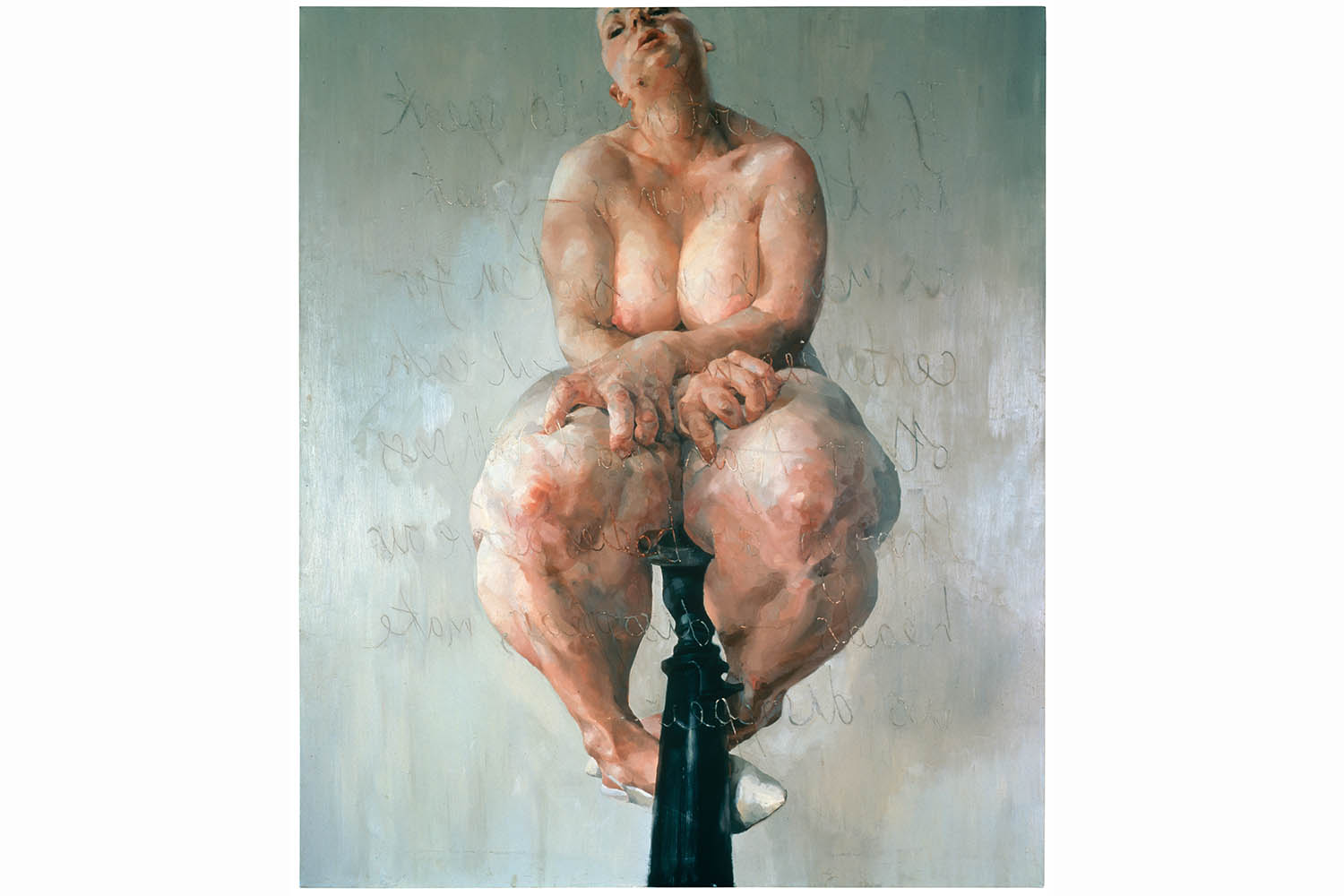

You can see this painting in her aptly enormous National Portrait Gallery retrospective, Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting. It shows the artist naked on a stool, thighs splayed, knees pressing monumentally forward against some writing on the mirror (necessarily backwards on the canvas) by the feminist theorist Luce Irigaray. But what you see is scale, not girth. For all the cliches, Saville does not paint “fat ladies”: obesity is not her subject: it is paint.

‘Grandiose’: Jenny Saville’s Propped, 1992

‘Attention-seeking marks’: Reverse, 2002-3

They are certainly pushing her painterliness hard at the NPG. A timeline relates Saville’s encounters with Titian, Venice, and old and modern masters such as Willem de Kooning. We are supposed to locate her in a portrait tradition. But what does she add to this genre beyond gigantism: absolutely massive bodies and heads, so huge the viewer is dwarfed in front of the canvas, gawping at nubs and flecks and flesh tones, at swathes and swipes with the palette knife, latterly with outcrops of livid green and bloody red.

You cannot discern any human personality in these portraits, and perhaps that is the point. They ask you to stand back to perceive the likeness, inert and photographic, but to come forward to be awestruck by the surface.

The naked body is a landscape, declares one painting, contour lines laboriously drawn in case you missed the point. The body is an object, declares another, piling up people like mattresses. In some of Saville’s muckle head shots, it is hard to tell whether you are looking at a boy or a girl (perhaps that’s deliberate: there is a highly conspicuous rainbow in one image). Identity is not vouchsafed in a face.

Up to four metres high, the works are so grandiose you expect their scale to have meaning or effect. Yet this show is almost instantly null. Heads are turned on their sides to no obvious purpose. Sightless blue eyes are more about intense colour than the subject’s blindness. Saville, in one self-portrait, looks beaten to a pulp – or is she just the occasion for a lot of scarlet pigment? Do these portraits ever derive from actual human lives?

Saville’s drawings from old master paintings are highly accomplished palimpsests, where you see one figure shifting beneath another, though without any sense of reason or purpose. But the paintings, with all their slick fusions and attention-seeking marks, their increasingly irradiated palette and almost kitsch efficiency, look like AI before its time: all depiction, no spirit.

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams is on at the Courtauld, London WC2 until 14 September

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting is at the National Portrait Gallery, London WC2, until 7 September

Photographs by The Easton Foundation/David Hall Gallery/Gagosian