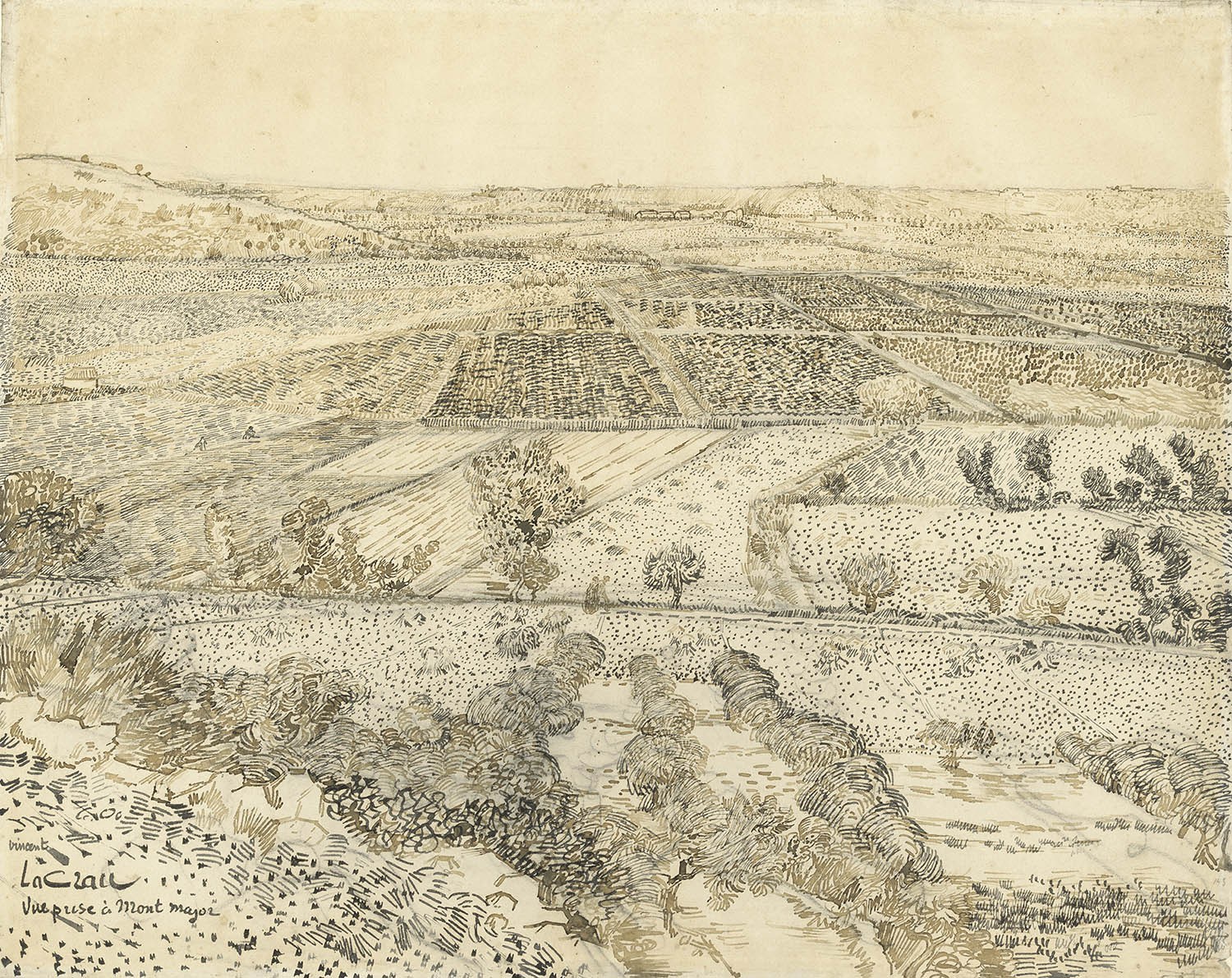

Provence in July, and Van Gogh has climbed a crag in dazzling heat to witness the wheat fields below, “streaming away”, he writes, “like the surface of the sea towards the horizon”. The mistral burns his face, insects afflict him and still he must praise this view. The result of his persistence appears exactly halfway through the Royal Academy’s remarkable double act of a show with the German titan of modern art Anselm Kiefer. It is astounding.

The landscape is a force field of dots, whorls and hyphens, minims and commas, notations that flow like music through the image while somehow describing the topography in hypnotic detail. Tiny figures scythe the harvest, chaff rises like haze and the bright horizon holds a seaside promise, as if there really was water beyond. And all of these sensations – heat and dust, scent and colour, pulsing summer vibrations – are achieved entirely with pencil, reed pen and ink.

This stupendous drawing is the heart of the show. Van Gogh’s pen is not much more than a sharpened stem, yet his wheat fields are tidal, his vision elemental. You see this all over again in the winter landscape that hangs directly opposite at the RA. Van Gogh sees and paints the snow in billowing waves of sea green, sparkling opal and grey. Nothing ever lies still in his art.

And all of this energy and persistence, this hard-won struggle to find the force of life in a landscape are there in Kiefer’s work, too, if in different ways. Kiefer/Van Gogh presents a dozen or so images by each artist, judiciously selected to show affinities, and to illuminate each through the other’s work. Kiefer’s paintings were specifically made with Van Gogh in mind. Yet anyone glumly predicting that all the glory will all reflect upon Kiefer – a belated gift, almost, for the artist’s 80th birthday in March – may well be surprised.

It doesn’t look that way at the start. Kiefer’s canvases are the largest you will ever see in a gallery; the biggest at the RA is about 9 metres (30ft) wide. They can be magniloquent, overloaded and turgid. There are harvest landscapes here where thickets of real straw stand so proud of the surface you can look right inside them, half expecting a mouse; and pigment so thick a single impasto whorl requires a whole tube.

‘The heart of the exhibition’: La Crau Seen from Montmajour, 1888, by Vincent van Gogh.

And where Van Gogh is surviving on sous, sometimes working on cotton or cardboard, Kiefer actually gilds his exorbitant harvests. Gold leaf twinkles across acres of paint, flecking stem and stubble, coating sunflower seeds, blazing across wide skies where harbinger birds circle, caught up in the escalating cost.

But the sincerity of Kiefer’s reverence for Van Gogh is never in doubt. As a student of 18, he followed in Van Gogh’s footsteps from the Netherlands to Belgium and down through France. The drawings he made on this pilgrimage, shown here, enter the landscape of Van Gogh’s mind as well. Kiefer makes a charcoal sketch of a local girl in Arles, unformed, but whole-hearted in its respect. It hangs next to Van Gogh’s tender portrait L’Arlésienne, that open-faced woman with a copy of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol on her table, the hand at her cheek bent like a pollarded willow.

One of Kiefer’s drawings, from 1963, shows a rutted path disappearing into a furze-fringed distance. He seems to hold it in mind all the way to The Crows in 2019. A pink and terracotta road stretches away through burned-out fields of charred stalks, blackened stems and scorched earth; the aftermath of fire or war. It is as much one of Kiefer’s devastating landscapes, riven with 20th-century horror, as a recollection of Van Gogh’s late Wheatfield With Crows. But the enormous sky is gilded, as if in homage to the amazing radiance of Van Gogh’s skies, whatever their hue. And that gold is still ringing in your eyes when you come to L’Arlésienne, startled at how much more light there is in her pale pink blouse than there ever could be in reality.

The middle gallery is hung with smaller and more pensive works. Van Gogh’s Country Road in Provence By Night is a drawing of wintry melancholy, a loner drifting home as the dusk draws in. His pen catches the skeletal leaves and bare ruined trees with fragile acuity. A slight brightness at the centre draws the eye in – very gradually, very closely – to the last surviving plants in a garden behind a gate.

It’s impossible to look at Kiefer’s rutted striations without thinking of every war going on

It’s impossible to look at Kiefer’s rutted striations without thinking of every war going on

And that is the action of this show, too. It allows for slow speed and powerful attention. You notice the waves undulating through Van Gogh’s Dutch gable facades, the bodily association between men and trees, the way his cross-hatching shimmers and his rivers of orange, umber and scarlet turn into poppy fields. How Kiefer’s palette flares into turquoise, gold and verdigris, and his horizons rise, when he thinks of Van Gogh.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Kiefer’s The Starry Night – many times the size of Van Gogh’s beloved masterpiece – is both swaggeringly extravagant and yet also poignant. It reprises Van Gogh’s whirling moon and stars, the Milky Way like a great dragon between them, in straw and pigment and sunflower seeds. Van Gogh’s chair, his flowers, skies and fields are all connected in these materials, as well as the motion of Kiefer’s painting.

Nevermore, 2014, by Anselm Kiefe.

Yet the sense is of spectacle, more than heart and soul. And to see these artists together is to realise that their immense labours – what Kiefer refers to as their struggle, in the show’s catalogue – lead in different directions. Van Gogh towards passion, jubilation, an intensity of truth and emotion: “I still love art and life very much,” he wrote to his brother, days before shooting himself in a field.

Whereas Kiefer’s is an art of history, narrative, convulsive upheaval; painting very often the expressive means to a political end. If Van Gogh’s sunflowers are all radiance, as Simon Schama observes in the catalogue, Kiefer’s are all radiation. But there is a marvellous convergence in the last room, where Van Gogh’s fast-beating heart seems to come alive again in a 2019 epic by Kiefer. The Last Load is almost entirely monochrome, a raking thrum of black, white and grey furrows rolling away towards a seam of dying light beneath night-darkened skies. Straw stands in charred stooks. Weeds grow. Something, or someone, is tangled up in these fields.

It is impossible to look at Kiefer’s rutted striations without thinking of every war going on, and every war where human beings were dragged to their death across the landscape. The painting puts the viewer on this side – the safe side – of this terrible road to evil. But what you see here, too, are Van Gogh’s high horizons and living lines, his impassioned light and darkness, his brimming emotion. Which may be why this is, by some way, the greatest Kiefer in the show.

Kiefer/Van Gogh is at the Royal Academy, London W1 until 26 October

Images: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent Van Gogh Foundation), Charles Duprat © Anselm Kiefer