“We delight in the beauty of the butterfly, but rarely admit the changes it has gone through to achieve that beauty,” wrote the great American poet and memoirist Maya Angelou. This month we are lucky to have two remarkable memoirs published by women writers who are not afraid of tackling the good and the ugly, the hopeful and the painful, the light and the shadow.

Memoir, as a genre, allows for both individuality and universality. It intertwines harsh reality with bold creativity – as in the title of Goethe’s early autobiography From My Life: Poetry and Truth. In the 18th century and throughout the romantic period, the genre was dominated by male writers: Goethe, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, William Wordsworth, Alexandre Dumas. Meanwhile, women’s accounts of autobiography, unless they were deemed to be spiritual or mystical by nature, have been to a large extent neglected, pushed to the periphery. That, however, has changed profoundly in the last hundred years. There is a growing recognition that women’s writing has contributed enormously to the trajectory of the genre, opening up important conversations not only on selfhood, but also on gender, identity, hierarchy, power and, ultimately, resilience.

In Mother Mary Comes to Me, Arundhati Roy introduces us to a character who has shaped her life and her writing in more ways than one: her mother, Mary. “She was my shelter and my storm,” Roy writes – and, as the book progresses, Mary’s abundant contradictions become increasingly apparent. On the one hand, there is no doubt this is an incredibly courageous, strong and independent-minded woman; a visionary, a dreamer and a warrior in a strictly patriarchal culture. A Syrian Christian from Kerala, she stands up to the inheritance laws that discriminate against females, defending her rights against her own family and paving the way for other women in her community to attain equal opportunities.

But there is a cold and cruel side to Mary’s mercurial personality that she displays in full force in her treatment of her own children. A dedicated educator and the founder of a prominent co-educational school, she radiates light when she is alone with her students, generously and patiently helping them, while reserving the dark side mostly for her daughter and son. The magic of Roy’s writing is her ability to take that “gift of darkness” and turn it into a narrative of love, compassion and wisdom.

Roy, born in north-east India in 1961, describes her childhood as fugitive. Her father was an alcoholic and the children would not meet him properly until they were in their 20s. Moving between different places with her mother and brother, it was a fragile, fractured existence. They took refuge in a cottage that belonged to Roy’s maternal grandfather, not as tenants or owners, but as “squatters” and “interlopers”, since the law – and the rest of the family – maintained that daughters had no right to their father’s property.

Bright and perceptive, Roy understood at an early age that behind every story of pain there is the shadow of another one. Unless we break the chain, daughters who were badly hurt or sons who were terribly bruised could become abusive parents themselves. A keen observer of cycles of suffering, Roy pays meticulous attention to the unseen, the unheard. She knows, almost intuitively, that the child must grow up fast. She is the mature one in this relationship, not the mother. She must develop an ability to journey into the psyche of other people, including the woman who has given birth to her, and see the past and the present through her eyes. But that also necessitates a distance – physical and cognitive – at least for a while. At the age of 18, Roy leaves home. Mother and daughter do not see each other for seven years. “I left my mother not because I didn’t love her, but in order to be able to continue to love her. Staying would have made that impossible.”

Reading this fascinating memoir, I was intrigued by Mary’s contradictions and could not help thinking she would make a great character in a novel. Her whole life, Mary keeps swimming against the current, often on her own. She strives to carve out a space of freedom and dignity for herself and other women and yet, once she becomes the warrior that she needs to be in order to survive, it is almost as if she cannot stop picking fights. It is equally interesting that Roy and her older brother grow up under the same roof, facing their mother’s wrath, but they have very different childhoods and memories. “He remembered a better life. He remembered our father and the big house we had lived in on the tea estate. He remembered being loved. Fortunately, I didn’t.”

You might expect someone who has no recollection of being loved to adopt a bitter or vengeful tone when writing about the past, but at no point does this memoir veer in that direction. There is genuine compassion in Roy’s writing: an honest desire to understand her mother – who died in 2022, aged 88 – and not to judge. Roy does not impose a view or verdict either, making space for the reader to come up with their own interpretation of events. We get the sense that, as much as her mother’s overwhelming presence in her life, it is also her father’s absence that has made her the brilliant writer she is today.

You might expect someone who has no recollection of being loved to be bitter, but at no point does Roy veer into this

You might expect someone who has no recollection of being loved to be bitter, but at no point does Roy veer into this

One of the hardest tasks for a storyteller from India or China or Turkey, like myself, or anyone from a wounded or shattered democracy, is that if you are a storyteller you also need to be a silence-teller. Literature, at its heart, is an effort to bring the periphery to the centre, make the unheard better heard, rehumanise those who have been dehumanised. There is a price to this. When you write about the underbelly or the periphery, when you call attention to the suppressed, the forgotten, the erased, you can easily be accused of not presenting your country in a good light. Not being “patriotic enough”. This is ironic, because only a writer who deeply loves their roots and their people would care about the suffering and the inequalities strongly enough to write about them. Behind every authorial criticism there is love, consideration and care. ‘The more I was hounded as an anti-national,” Roy writes, “the surer I was that India was the place I loved, the place to which I belonged.”

This complicated sense of belonging to a place and culture is strongly present in Jung Chang’s beautiful and moving memoir Fly, Wild Swans: My Mother, Myself and China. Her earlier book Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China, published in 1991, remains the most widely read English-language autobiography by a Chinese writer. Although it has sold more than 15m copies worldwide and left a huge impact on countless readers across national borders, it was banned in China. I read it many years ago and still remember vividly its account of how Chang’s grandmother experienced the horrific custom of foot-binding as an infant because of patriarchal standards of female beauty. And how both parents suffered horribly under the Cultural Revolution as they were denounced, imprisoned and tortured.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

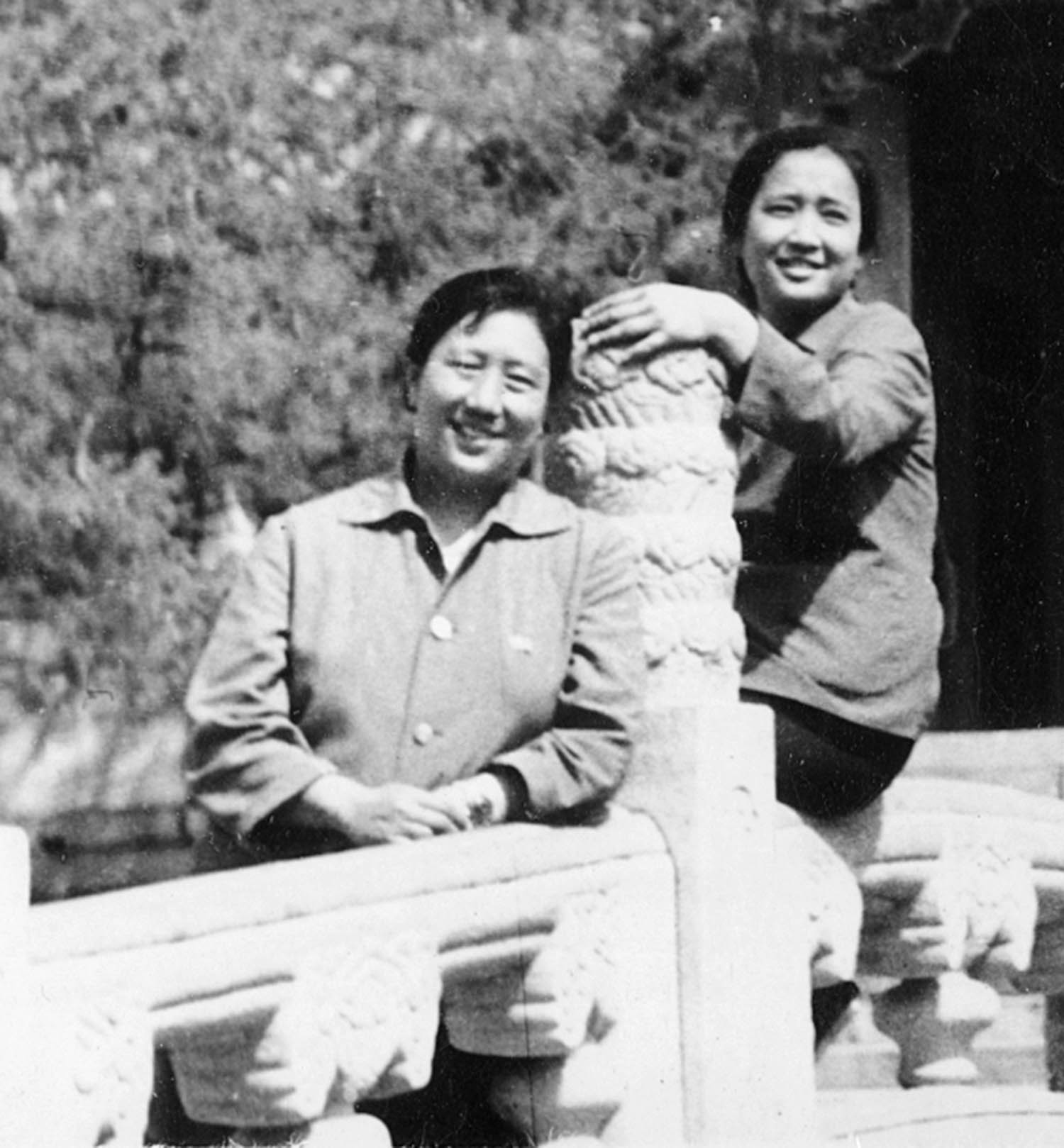

Jung Chang with her mother before she left China in 1978.

One of Chang’s earliest memories of living under Mao is in nursery school, when her mother came to see her but could only stay for a limited time as she had to urgently return to detention. Chang remembers holding hands with her through a barrier. As I journeyed through her new book, I could not stop thinking of that powerful image. So much has changed since her early years in China, but there is also much that hasn’t changed enough, and it is as if the mother and daughter are still holding hands as they remain separated by an invisible barrier. Since 2018, it has been too dangerous for Chang to visit China, where her 94-year-old mother is in a nursing home.

Born in 1952 in Sichuan province, Chang was only 14 years old when Mao launched the Cultural Revolution. It was one of the most brutal and bloody eras in Chinese history, lasting from 1966 to 1976: a time of destruction, paranoia and a ruthless purge “to clear away the evil habits of old society”, as announced by the party’s official newspaper. This chilling call prompted the Red Guards and gangs of students in military fatigues to search for “enemies of the people” – ordinary citizens who were accused of having bourgeois habits or even wearing bourgeois clothes. Intellectuals, writers and artists were systematically targeted alongside countless others. Historians estimate that between 500,000 and two million people lost their lives during the period. Mao’s Little Red Book was imposed on everyone, with collective reading sessions being organised, and people of all ages forced to listen: from passengers on public transportation in big cities to peasants working in rice fields.

Chang concluded her earlier memoir with the end of the Mao era. In 1978, she was among the first Chinese people to leave communist China for the west. She was also the first person from communist China to receive a doctorate from a British university. Now almost half a century on, writing with unflinching determination once again, she has published a sequel to Wild Swans, but one that reads perfectly well on its own.

The Great Famine (1959-1961) decimated the population, causing more than 40 million people – most of whom were peasants – to die of starvation. Chang remembers walking with her parents when she was little and coming across a woman in tattered clothes, cradling an emaciated baby, begging for help. Her mother immediately pressed money and her food coupons into the woman’s palm, even though the party had strictly forbidden their members to give to beggars: “Had she lived in a democratic system,” Chang writes, “she might make a good member of parliament as she was genuinely dedicated to tackling grassroots issues.”

Chang displays extraordinary courage, even at the expense of personal risk or risk to her family

Chang displays extraordinary courage, even at the expense of personal risk or risk to her family

Braiding her own story with that of her mother’s, Chang skilfully sheds light on the transformation that the nation as a whole has gone through. Half a century ago, China was a low-income country with a gross national income per head less than that of Zambia. Today, it is a juggernaut of such military and economic strength that it is fast reshaping the global balance of power. Chang never shies away from addressing the problems of the regime while at the same time expressing her love for the culture and the people. She displays an extraordinary courage, even at the expense of personal risk or risk to her family. “It became clear to me that my life would change after the publication of the biography, that Beijing would view me as a kind of enemy, and I had to be prepared for the worst,” she writes.

With the political climate changing and hardening, Chang cannot visit her mother. It is moving to read about how, gazing at her increasingly enfeebled frame on a video call, Chang recognises that this is the woman she owes her freedom and her happiness to, and who made her the person and writer she is today.

Deliciously different in tone, style and subject, these two memoirs share a similar clarity of thought and generosity of heart. In some ways, both are love letters. They show us, with a gentle and hard-won wisdom, that we do not forget our mothers, or our motherlands, even when we are miles, continents or “worlds” away from them. We carry them with us wherever we go.

Mother Mary Comes to Me by Arundhati Roy is published by Hamish Hamilton (£20) and Fly, Wild Swans by Jung Chang is published by William Collins (£25). Order either book from The Observer Shop to receive a 10% discount. Delivery charges may apply

Jung Chang will be in conversation with Erica Wagner at the Manchester Literature festival in partnership with The Observer on 19 October 2025

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Photography of Arundhati Roy and her family by Mayank Austen Soofi; Jung Chang and her mother courtesy of the author