For this first weekend in October, in 1781, the Rev Gilbert White’s daily report runs as follows:

Sunday 7

30. 53. W, N.

Cold dew, sun, sweet weather.

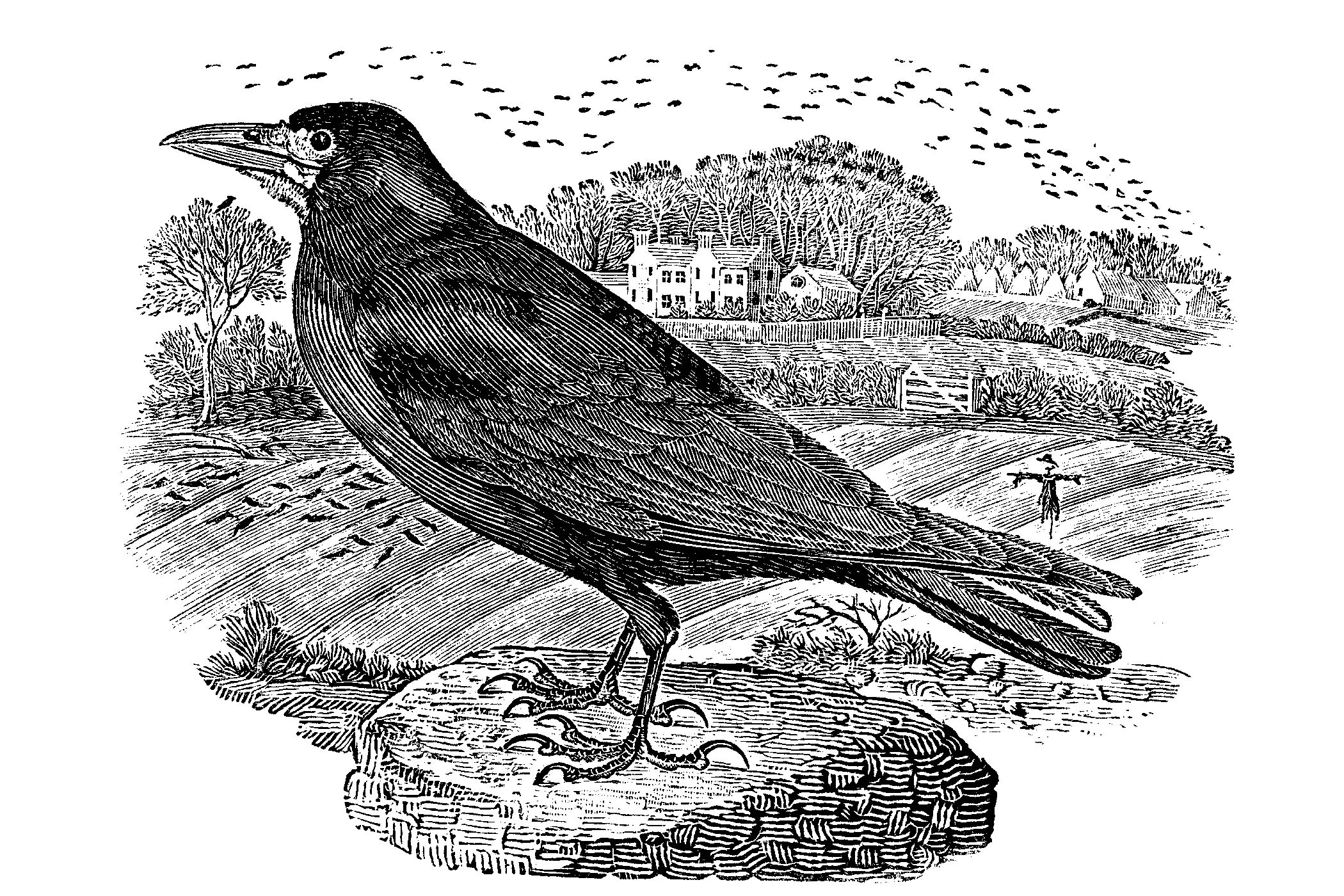

Not one hirundo to be seen. Fleecy clouds, & beautiful gleams of sunshine. Rooks carry off the wallnuts from my trees.

In his Hampshire valley, tucked into the south downs, the north-west wind had taken the last of the swallows and martins away, and a beautiful autumn day had dawned. The temperature is 30F, and the barometer reads 53 inches of mercury. “Began to light fires in the parlor,” White had noted the previous week. The house was starting to feel the chill, and the northern lights had been flaming red and vast in the night sky.

Gilbert White’s celebrated The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, never out of print since it was first published in 1789, was a form of autobiography, a work of 18th-century creative nonfiction woven out of the annual progress of frost, seeds, birds, trees, insects, clouds and bees. As Jenny Uglow writes, in this, her own glorious tribute to his journals, White was not an aspirational scientist, but “more of a philosophical muser”. His was a “new kind of writing”, she says, “imbued with such feeling”, linking “scholarly knowledge to simple daily watching”.

Curiosity was everything. Every day, in an almost monk-like way, he records the temperature, wind direction and weather conditions, then adds his own comments on the state of the natural world around him. In so doing, he anchors himself in time and space; he becomes his own literary work of art, personified.

Uglow’s literary response is equally vivacious. Deftly, discursively, she relives one chosen year of White’s journals – 1781 – and presents us with little essays, laid out day by day, month by month, each detailing White’s statistical reports, then expanding knowledgably and entertainingly on every aspect of his experience, from the fortunes of family to habits of animals and peculiarities of plants.

In the process, Uglow shows the powerful contemporary relevance his journal has for us as a record of what we have lost in our much-changed climate – and yet she is also startled by the discovery that “so much is still the same”.

Selborne is White’s microcosm of the late 18th-century world, in the same way that Walden Pond would be the test bed for Henry David Thoreau’s philosophies in the 19th century, or a nuclear shingle garden in Dungeness would, for film-maker Derek Jarman, echo the urgencies of the 1980s. White is by no means political; but he too uses a certain seclusion and microscopic focus to survey the greater world and its values.

The Rook by Thomas Bewick

His village lies almost hidden around him, “embraced by the landscape”, protected by hangers of beech trees. Selborne is a “busy, clattering place”, threaded through by a single thoroughfare, delightfully named Gracious Street. If this all sounds a bit Austeneseque, it’s no coincidence: Chawton, where Jane Austen would later live, is just five miles away.

White’s house, the Wakes, facing the church, stands at the centre of this little universe, and his journal has the air of a botanically minded Miss Marple, with White 60 years old when we meet him, a lively country curate, determined to solve the latest mystery, perhaps a murder of crows. He even has an assistant and factotum in his tasks, to whom he is devoted: Thomas Hoar, six years his senior, who, as White’s hearing starts to fail, “often hears things before him – the rush of wind in the hop-poles and bean-sticks, the first twittering of martins under the eaves”.Uglow aptly quotes Virginia Woolf: “No novelist could have given us more ... completely all that we need to know before the story begins.”

Aptly, because that is exactly what Uglow does with her own book. Her framing narrative, too, is full of human and animal characters, with quirks and conundrums that she addresses with modern updates. Do martins fly south for the winter, or hibernate in burrows?, White asks. (The former.) What happens if you put a tortoise in a bowl of water? (We shall see.)

The movements of White’s own extended family, living all around and beyond, are recorded in the same way. He describes his brother’s family setting out for a summer holiday in Ringmer in Sussex in a Dickensian convoy of “Harry and his wife (no small personages) and seven children, two canary birds, one aberdavine [a species of finch], 10 parcels, a dormouse, and a puppy-dog, all ... in two post-chaises.”Such human migrations are set alongside the reproduction of eels and the swooping of owls, while rooks fall from the trees with frozen wings in a great frost, and a dead bittern – “a surprising beauty” of a waterbird – once dressed and cooked, makes for good eating. (To which Uglow adds her mordant note: by 1897, the same birds will have been “shot to extinction in Britain” – though they have since returned.)

White’s fascination runs from the stars up above to slugs covered in slime – and to Timothy the tortoise

White’s fascination runs from the stars up above to slugs covered in slime – and to Timothy the tortoise

White needs to know about everything he can. Now. Urgency is all. His fascination runs from the stars up above down to “slugs, which are covered with slime, as whales with blubber”, and to Timothy the tortoise (in fact a female), who patrols his master’s fantastical garden – complete with its obelisks and gothic hermitage and quincunx of spruces, along with a rather pantomime painted wooden figure of Heracles.

Timothy is doted upon by White and Hoar. “Timothy the tortoise possesses a greater share of discernment than I was aware of; & is much too wise to walk into a well,” White writes. And when, in the spirit of science, he decides to test if Timothy is amphibious and dunks the reptile in a tub of water, he watches as Timothy sinks to the bottom and, unsurprisingly, “seemed quite out of his element, & was much dismayed”.

You will be glad to know that Timothy survives, finding a nice spot in the hedge, “in a very comfortable, snug manner ... he will have the warmth of the winter sun”. We rather hope for the same for his master, Mr White, who is conjured up by this magical book, so beautifully illustrated with woodcuts by Eric Ravilious and Thomas Bewick, whose birds hop out of the pages like sentinel spirits, embodying both White’s and Uglow’s perennial sense of perky curiosity.

A Year With Gilbert White: The First Great Nature Writer by Jenny Uglow is published by Faber & Faber (£25). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £21.25. Delivery charges may apply

Philip Hoare’s William Blake and the Sea Monsters of Love is published by 4th Estate.

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Illustration of Gilbert White in his garden by Eric Ravilious, courtesy of Faber

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy