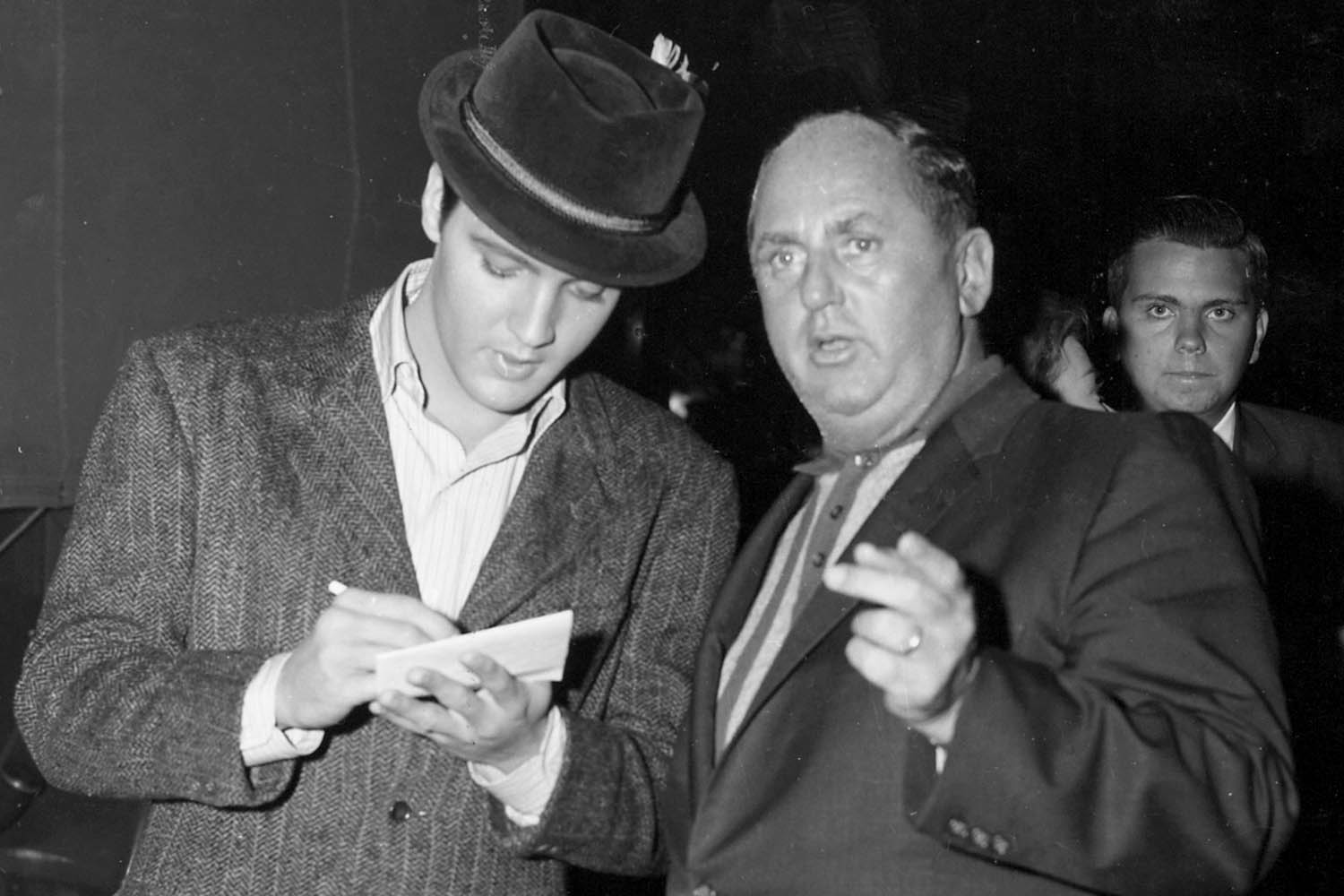

Colonel Tom Parker first saw the 20-year-old Elvis Presley perform live at the Louisiana Hayride on 15 January 1955. Though bemused by the raw rock’n’roll music being played, the wildly enthusiastic reaction of the young audience alerted him to the presence of a star in the making.

He immediately set out to wrest control of the young singer’s affairs from his manager, Bob Neal, and producer, Sam Phillips, whose Memphis record label, Sun, had released the early rock’n’roll singles that had ignited Elvis’s career and dramatically altered the course of popular music.

By November of the same year, Parker’s tenacity had paid off; he watched as his new charge signed a lucrative deal with RCA records, a major label. Soon after, Presley penned an emotional thank you letter to “the Colonel”, describing him as “the best and most wonderful person I could ever hope to work with”. He signed off, “I love you like a father.”

As Peter Guralnick’s meticulous mapping of their ensuing relationship makes clear, Parker would soon assume the role of a controlling parent, smoothing the singer’s rough edges to make him more palatable to a mainstream audience, committing him to a series of formulaic films that shamelessly milked his heart-throb status and guiding him inexorably towards the showbiz mecca of Las Vegas.

For Guralnick, though, Parker is a man more sinned against than sinning, a flawed visionary whose intentions, though often shortsighted or misguided, were always driven by his utter loyalty to his artist. Guralnick is a doyen of American music writers, the author of the definitive two-volume biography of Presley, Last Train to Memphis (1994) and Careless Love (1999), of which this book is a coda.

At its centre is the Colonel, whose self-conferred title lent him an air of credibility in the cut-throat postwar music business. His down-home charm, which won over Presley and his parents, was undercut by a steely ruthlessness in business matters. Although Guralnick maps out his relentless wheeling and dealing in exhaustive detail, he remains an elusive figure throughout, which is just as he would have preferred it.

Born Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk on 26 June 1909, in Breda in the Netherlands, the fourth of 11 children, he was, Guralnick writes, “a strange child”. He ran away from home numerous times and in later life, though he often spoke movingly of his mother, he refused to acknowledge his father except to describe him as “no good”. Parker’s second wife recalls how he could not bear to be touched, evidence surely of childhood trauma, but also describes him as “a relentless, if very complicated, optimist, who never passed a mirror without smiling”.

In 1929, that optimism propelled him to America. After a stint in the US Army, he worked with various travelling circuses and carnivals, assuaging for a while his restless temperament, if not his remarkable will to succeed.

“He did everything and anything that was asked of him,” writes Guralnick, which included selling candy apples, unloading trucks and even washing the elephants. In 1939, he took over the running of a travelling show called Star-O-Rama and, through an extravagant billboard campaign, briefly revived the career of Gene Autry, the “Singing Cowboy”, who, as Guralnick puts it, was “one of the first pop superstars”.

Elvis signed off a thank you letter, saying, ‘I love you like a father’

Elvis signed off a thank you letter, saying, ‘I love you like a father’

It was an apprenticeship that served Parker well when he gravitated towards the postwar music business, where he found success in the 1950s managing country and western performers such as Hank Snow and Eddy Arnold. Then came Elvis, a new kind of pop performer, whose onstage aura – instinctive, sexually charged, drawing on black rhythm and blues – Parker immediately recognised, but seems never to have fully understood. What followed was a taming of the singer’s Dionysian thrust. Great crossover success followed, but at an immeasurable cost to Presley’s credibility, creativity and eventually his soul and spirit.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Guralnick challenges the long-held assumption that the prime reason Elvis never performed outside of America was Parker’s deep fear of being revealed as an illegal immigrant and being denied entry back into his adopted country. As evidence, he cites a mooted tour of Japan in 1974, which was considered then dismissed because of security and immigration issues around Elvis’s spiralling prescription drug use. This hardly explains the countless other lucrative touring opportunities that were on offer, but never accepted. What seems more likely is that Elvis would not countenance touring abroad without the Colonel, so unhealthily codependent was their relationship.

In the end, the intertwined destinies of the King and the Colonel rose and fell in tandem: Elvis retreating into a narcotised life of indolence, overindulgence and “uncontrollable spending” behind the doors of his Graceland mansion; Parker seeking refuge at the Las Vegas blackjack tables, where he sometimes lost six-figure sums in a single night.

“They were locked in a relationship of mutual denial,” writes Guralnick of their once seemingly unbreakable bond, “just as they had always been linked by proximities of character and temperament not visible to the outsider.”

Elvis’s story has been told and retold so often that it has attained the character of a latter-day Greek tragedy. Colonel Parker’s journey will always be an addendum, albeit a fascinating one. As it unfolded in this doggedly detailed telling, I sometimes found myself longing for the semi-novelistic style of more extravagant music writers such as Stanley Booth or Nick Tosches.

Despite Guralnick’s attempts at character rehabilitation, Colonel Parker, who died in 1997, aged 87, emerges as a driven deal-maker who happened to be in the right place, though arguably at the wrong time. Sincere in his love for and loyalty to the star he helped create, he was nevertheless so rooted in an older ideal of showbusiness – where the lucrative and the banal existed in uneasy harmony – that the possibility of creative reinvention always seemed secondary, even unnecessary.

And yet, as Baz Luhrmann’s 2022 biopic attests, the myth of Elvis the King that the Colonel helped create, and maintain, endures – 70 years after their paths first crossed. “It’s still Elvis and the Colonel,” Parker said in the wake of the former’s death. For better and for worse, that was always the case.

The Colonel and the King: Tom Parker, Elvis Presley and the Partnership that Rocked the World by Peter Guralnick is published by White Rabbit (£35). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £31.50. Delivery charges may apply

Photograph courtesy of Graceland Archives