“Why are black people six times more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia than their white compatriots?” asked the professor. It was 1981 and that year there were only two identifiably black students among the intake of the London Hospital Medical College: Amaju Ikomi, a foreign student from Nigeria, and me.

The professor stood at the lectern. His eyes ranged across the auditorium and stopped at me. He waited. I was flushed with embarrassment. “Mr Grant, would you care to hazard a guess?” When it became apparent that I would not be drawn on the subject, he answered for me, averting his gaze and addressing the body of students. “Black people suffer a higher incidence of schizophrenia because black people are schooled in paranoia.” I was affronted by his assertion but I said nothing.

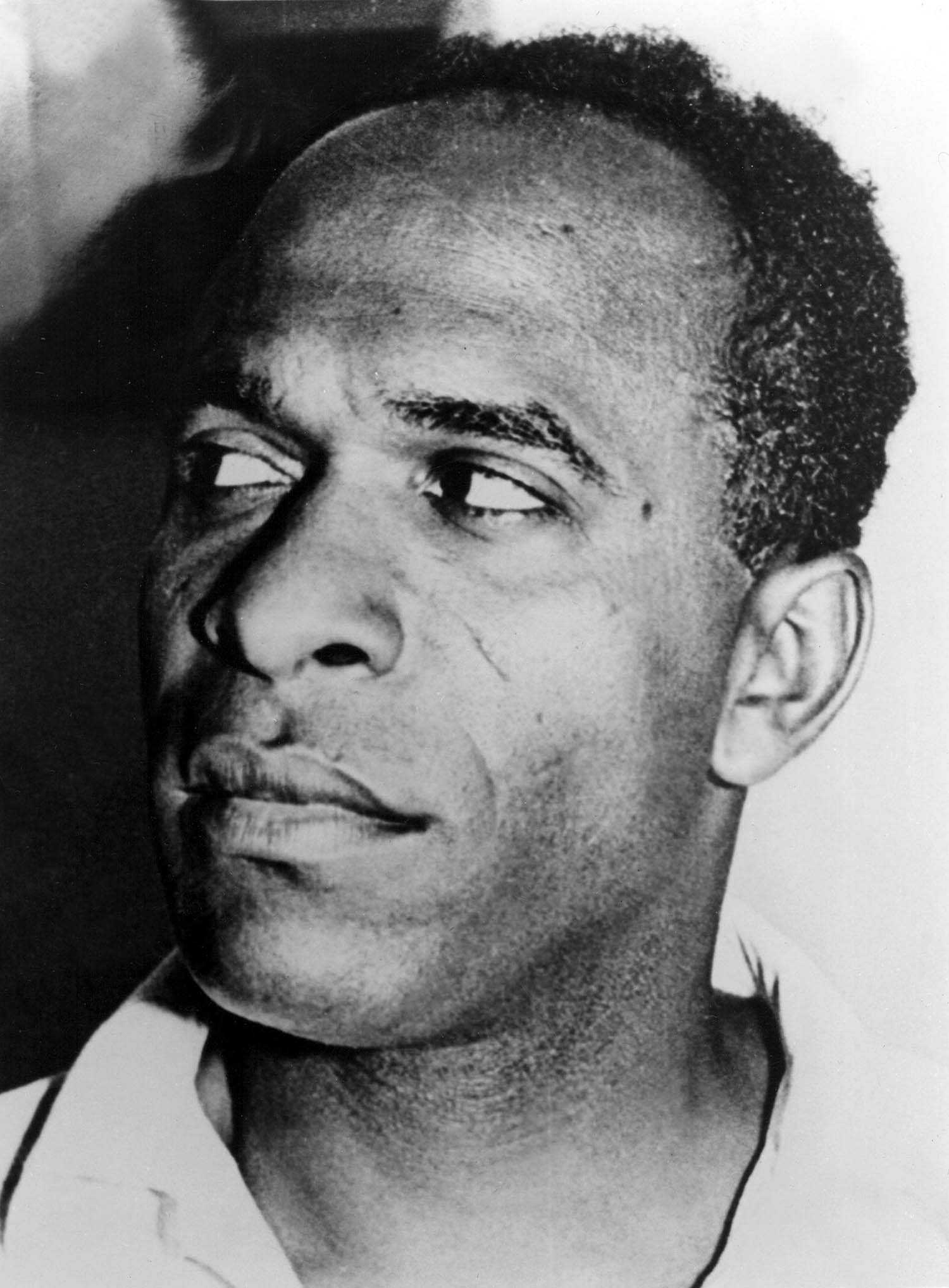

Had I read Black Skin, White Masks, I might have recognised that our lecturer was practising what Frantz Fanon called “the racial allocation of guilt”. Fanon, born 100 years ago in French-governed Martinique, was a radical psychiatrist who in the 1950s sided with Algerian rebels during their brutal war of independence from France. His book described the practice by white people in authority of getting black people to work against their own interests so that they fail to recognise white people as the real culprits of their oppression: enslavers and colonisers, he wrote, recruited “‘peoples of colour’ who annihilated the attempts at liberation by other ‘peoples of colour’”. During the period of the Atlantic slave trade, for example, the black slave driver did his master’s bidding in whipping the enslaved. The professor’s assessment was that, in the generations after abolition and colonialism, it was black intermediaries who wielded the whip of paranoia over their brethren. He had neatly absolved descendants of colonisers of their part in the mental ill-health of my black British peers.

Throughout my time at medical school, I had never heard of Frantz Fanon. Occasionally, I’d pop into Freedom Press, the radical bookshop on Whitechapel Road, but it’s unlikely I’d have picked up a book called Black Skin, White Masks. As the child of black Jamaican migrants, rather than being schooled in paranoia, I was drilled in not drawing attention to myself, in not foregrounding my blackness. Like Richard Wright’s White Man, Listen!, Fanon’s book would have seemed too on the nose for me then. I didn’t want to accept the possibility of my blackness being more of a stain than a simple birthmark or to consider that I might be a damaged victim of colonial history.

A decade earlier, there had been numerous stories in Luton, where I grew up, of troubled Jamaican youngsters being sent by their parents back to the Caribbean. When I asked my mum, Ethlyn, what was going on, she answered dryly: “Inglan mad dem.” Ethlyn’s sad observation came to mind later at medical school whenever I was assigned the task of looking after the pitiful black patients on psychiatric wards.

Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon’s first book, was written three decades before I studied to be a physician. Reading it now, I imagine Fanon would have reached the same conclusion as my mum about the assault on the mental health of the formerly colonised and their descendants in hostile environments, whether in Luton or Blida, Algeria, where Fanon practised.

“In psychiatry,” argues Fanon, “there are latent forms of psychosis that become evident following a traumatic experience.” Fanon died in 1961. He never used the phrase “generational trauma”, which only started gaining traction among psychologists in the mid-60s, but its notion haunts the pages of Black Skin, White Masks.

When I asked my mum why troubled youngsters were being sent back to the Caribbean, she said: ‘Inglan mad dem’

When I asked my mum why troubled youngsters were being sent back to the Caribbean, she said: ‘Inglan mad dem’

Fanon’s book has a youthful, searching urgency to it; he wrote it when he was 27 and had only recently completed his medical training. Frequently, it reads like a literature review of case studies of different types of texts – academic research as well as novels. Its purpose, he wrote, is “to enable the colored man to understand by way of clear-cut examples of psychological elements that can alienate his black counterparts”. I would argue that Fanon recruits himself as a case study for his thesis – an inquiry into the inner life of an intellectual and traumatised black man who shuttles between the white and black worlds, and who must make a choice about where his allegiance lies. That conundrum later resulted in Fanon electing to side with the Algerian rebels – a decision that challenged a core principle of medicine: first do no harm.

The book’s title echoes black people’s quest to mask their differences from their former colonial masters. But it also speaks to Fanon’s preoccupations in the book: the desire to eloquently match the coloniser’s language; an examination of the patronising tendency of his medical colleagues to mimic the pidgin French of their patients when treating them; the damage to the psyche of black people from the perils of interracial love; and an interrogation of the hierarchical racial code introduced by colonisers – what Fanon called the “epidermal racial schema”.

I wish I had been introduced to Fanon’s study 40 years ago at medical school; it would have helped to skewer the fallacy that black people had brought psychological misery upon themselves by schooling each other in paranoia.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Colin Grant is the director of WritersMosaic, a division of the Royal Literary Fund. His books include I’m Black So You Don’t Have to Be: A Memoir in Eight Lives

Black Skin, White Masks by Frantz Fanon is published by Penguin Modern Classics (£9.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £8.99. Delivery charges may apply

Photography by Alamy