Ringo Starr left the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s Rishikesh ashram earlier than his bandmates in 1968 – as might be expected from a ring-wearing dandy who many would assume was the least spiritual of all the Beatles. He had found meals at the ashram difficult, not because he was a Liverpudlian naïf abroad, but because a childhood of serious ill health had left his insides in a delicate state. Plus, his wife Maureen hated the insects. After less than a fortnight, they were out.

Starr was the band’s everyman, a seasoned pro sent aloft into stratospheric fame where his ready grin and quick wit made him an easy favourite Fab. And yet – in one of the revelations of Tom Doyle’s thoroughly researched book – it turns out that his habitual “peace and love” refrain isn’t just some rote catchphrase. It runs deeper. In recent years, since undergoing rehab in 1988, Starr has become a paragon of clean living, regularly snacking on seeds and, allegedly, smelling of kale. Crucially, he has said that he still treasures the personal mantra for meditation that the Maharishi gave him all those years ago.

Doyle’s portrait doesn’t exactly dismantle the public perception of the Beatles’ drummer, now 85, but reappraisals do come in this wide-ranging biography. Starr is, at once, beloved by Beatles fans for his charm, and routinely disdained by others for not being the songwriting equal of his colleagues. It’s true: he probably was a light entertainer trapped inside a late-Sixties revolutionary cultural force. But Starr was as witty as the other three, and more diplomatically inclined. And nicer to Yoko Ono.

As the pile of books and media about the 20th century’s most famous sons only grows – the multi-media Anthology project is being reissued and embellished in the coming month – Mojo writer and Paul McCartney biographer Doyle seeks to tease out the lesser-known stories from Starr’s extraordinary life – and to spotlight the occasions where he was crucial to the band’s dynamic. Doyle’s romp through Starr’s often bizarre post-Beatles career leads you to conclude that the past is another country, and incomprehensible quality control choices are made there.

Starr was born Richard Starkey in 1940, in Dingle in Liverpool; his parents split up when he was three and he stayed with his mother, Elsie. A burst appendix and peritonitis landed him in a coma, lasting several days, at the age of six. Further long stints of ill health featured in his young life, but during one hospital stay a music teacher introduced Starkey to percussion instruments and he was hooked. Starkey’s stepfather, Harry, encouraged the teenager by buying him a drum kit for Christmas.

Starkey would go on to become the mainstay of a series of skiffle bands; in 1962 the Beatles – a little younger, a little less experienced, but clearly going places – poached him from one successful touring act, Kingsize Taylor and the Dominoes, who had in turn poached him from Rory Storm and the Hurricanes. The name Ringo Starr was already written on his bass drum.

Doyle buries the cruel quip that Starr ‘wasn’t even the best drummer in the Beatles’

Doyle buries the cruel quip that Starr ‘wasn’t even the best drummer in the Beatles’

George Harrison was probably Starr’s closest ally throughout the life of the band, but Ringo managed to stay onside with everyone, most of the time. His relationship with McCartney was damaged in the turbulent aftermath of the band’s split, but they later reconciled. In 2015, McCartney insisted that Starr should be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in his own right. Ringo’s tight relationship with Harrison, meanwhile, even survived the affair between Harrison and Ringo’s first wife, Maureen.

Once and for all, Doyle buries the cruel quip – wrongly attributed to John Lennon – that Starr “wasn’t even the best drummer in the Beatles”. There is no record of Lennon having uttered those words. Instead, it was a throwaway line delivered by comedian Jasper Carrott in his 1980s show Carrott’s Lib, although another BBC Radio 4 comedy show had cracked the same joke before that.

Doyle, who is a drummer himself, also demolishes the idea that Starr was ever technically lacking. A studio hiccup very early on meant that producer George Martin subbed Ringo out; on a handful of Beatles tracks, for various reasons, McCartney sometimes played drums (Dear Prudence, The Ballad of John and Yoko). But Doyle makes the case throughout that, unless Starr is doing the thing that only he can do – drum steadily, instinctively, not showily, on a right-handed kit despite being left-handed, his stool too high so he has to crouch – it doesn’t sound like the Beatles.

Producer Jeff Lynne of ELO tried to sample and loop Starr for the Beatles’ last song, Now and Then. It didn’t work. “[Lynne] always wants a click track,” Starr noted, of the electronic metronome many musicians use to keep time, “and I’m telling him, “I’m the click!” Starr can’t do his trademark fills on command, either: “The fill comes when I’m emotionally involved.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Doyle comes to praise Starr not to bury him. But he still must devote great swathes of this book to the long decades in which Ringo spends time on umpteen hare-brained film productions and musical misadventures. Wisely, these sections are not blow-by-blow trudges. Doyle skilfully teases out themes and makes connections between Starr’s projects while cannily editorialising.

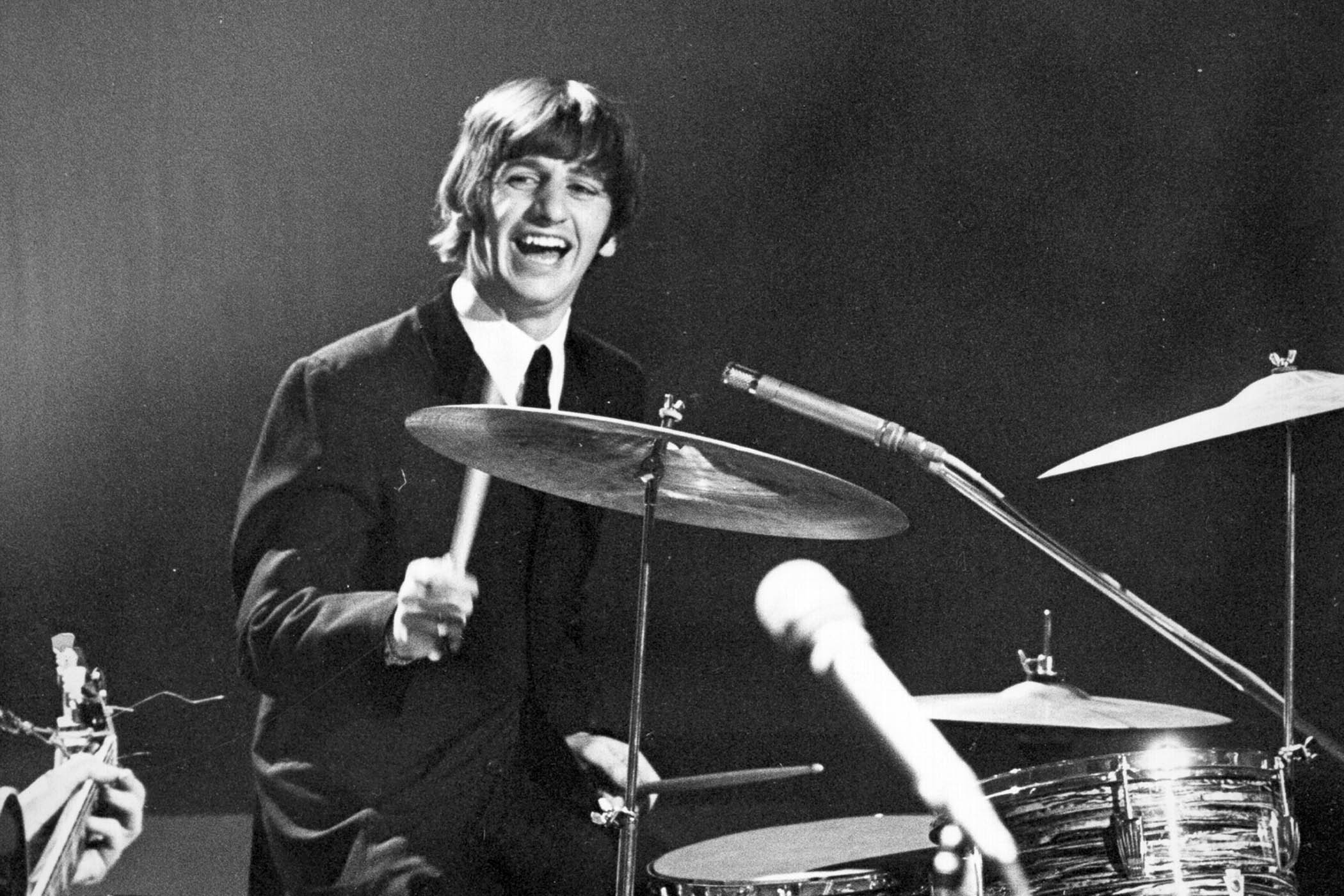

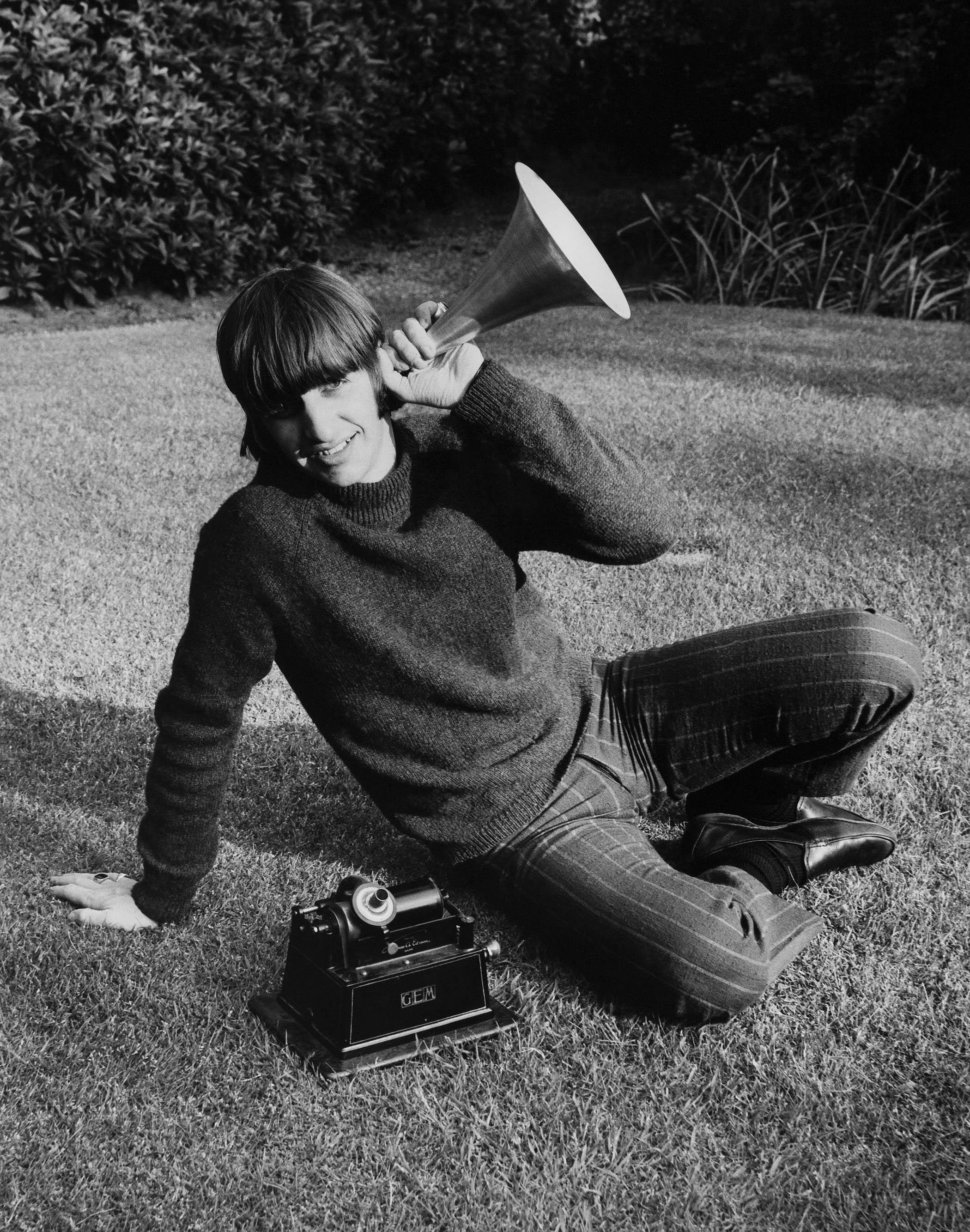

Ringo in his moptop heyday during the 1960s.

The cool furniture and interior design firm in which Starr partnered in the late Sixties thrived. And yet Ringo the film star specialised in terrible Mexican accents. He accepted ludicrous scripts that made no sense, like a bonkers Frank Zappa outing, 200 Motels. Ken Russell’s Lizstomania featured Starr as a licentious pope.

Elsewhere, addled jam sessions with other famous musicians in LA unfurl endlessly – episodes that practically have you tapping your watch, waiting for punk to come along. Tales of loaded musicians behaving badly are hard to get right. Doyle – to his credit – cringes regularly, while offering sympathy for the reasons a man deserted by his biological father might have abused alcohol and drugs.

Often, though, Ringo’s story turns heroic. Sometimes, his singles compete strongly against the solo work of the other Beatles (It Don’t Come Easy, from April 1971, is one goer). Such are his charms, he is able to talk sense to the notoriously paranoid producer Phil Spector. A fan of Marc Bolan, Starr directs his band T Rex’s concert film, Born to Boogie (1972). Although met with mixed reviews at the time, consensus has it that this empathic bottling of T Rexstasy, an obvious analogue to Beatlemania, stands up well.

Perhaps most incongruously of all, Starr becomes famous all over again for narrating the Thomas the Tank Engine TV show in the 1980s. It’s hardly groundbreaking material, but – unlike much of what has gone before – it’s a great piece of casting. Starr’s warm, bluff, Scouse delivery suits the material to the hilt.

Ringo: A Fab Life by Tom Doyle is published by New Modern (£25). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £22.50. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Photography by Gamma-Keystone/Getty Images