Pahá Sápa, the place was called. Is called. Should be called. Take your pick. “The hills that are black” in English, and, until the middle of the 19th century, this landscape was, as Peter Cozzens writes, the centre of the world of the Native American Lakota people. The hills of the mountain range that rises from the plains are covered in dark pine, hence the name. But in the autumn of 1874 – nine years after the end of the American civil war and, crucially, just one year after the Panic of 1873 (if you don’t know the details, you can guess) – a frisky soldier by the name of George Armstrong Custer discovered gold there, and a frantic stampede westward began.

Fly-by-night mining encampments with names such as Whoop Up and Golden Gate sprung up seemingly overnight in the Black Hills of what is now South Dakota and Wyoming; most of them vanished when their claims proved non-existent or played out. But some of them stuck: and the most storied of all was called Deadwood.

Most likely you know the place from the celebrated HBO series (2004-2006) created by David Milch. It seems fair to start with the series as that’s how Cozzens, an acclaimed American historian whose 2016 book The Earth Is Weeping: The Epic Story of the Indian Wars for the American West was the winner of a slew of awards, came to this history. Across three seasons (the show was cut short in its prime thanks to a dispute between Milch and HBO, though a film wrapping up the story was released in 2019), the series depicted a group of disparate, mostly lawless and hugely colourful characters – Wild Bill Hickok, Calamity Jane and the like – as they forged a kind of unity on a contested frontier and moved towards what we think of as “modernity” or “civilisation”.

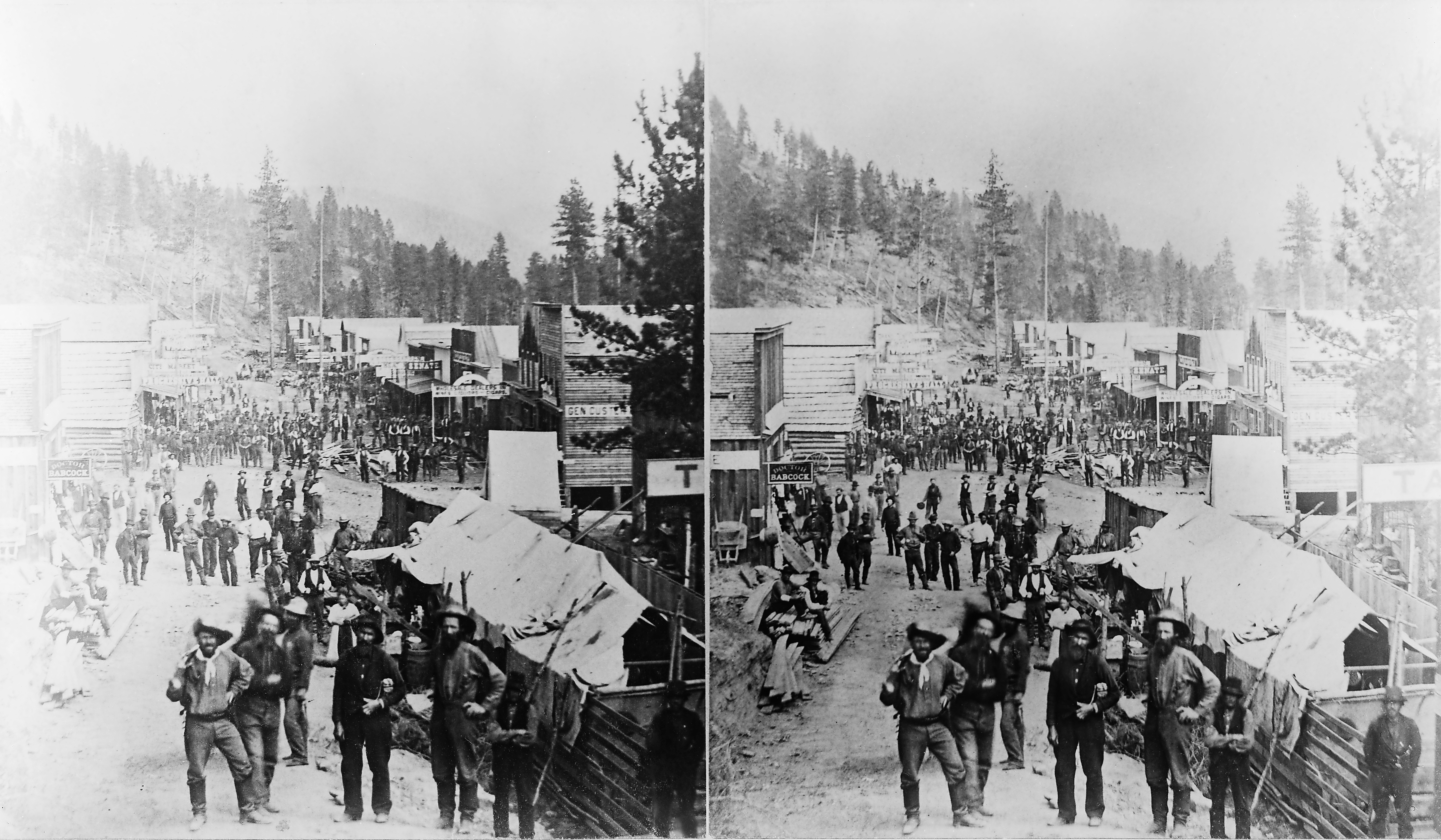

Main Street in Deadwood, South Dakota, circa 1875. Main image above: Calamity Jane at the Grave of Wild Bill in Deadwood, South Dakota, circa 1903

In the interests of plunging us straight into the lives of its central characters, Deadwood the series avoids, for the most part, the background to the place’s founding. It is the great strength of Cozzens’s book that it does not, and though what he has to relate may not be wholly surprising to those who know something of the American west, it is no less dispiriting for that. In short: in 1868, the Treaty of Fort Laramie was signed, and was meant to ensure that “the Lakota domain was to be inviolate; the peace permanent”, as Cozzens writes.

So the settlement of Deadwood was completely illegal, not that any of the miners and their hangers-on cared in the least. It was not until the spring of 1877, when President Ulysses S Grant’s commissioners coerced the Lakota into signing over their land, that Deadwood passed to official government control. “Capitalists could invest in the 147 quartz-mining claims in the northern Hills without fear of federal confiscation. Law-abiding townspeople breathed easier. Deadwood’s outlaw days were over.”

This is both an enjoyable and a serious book; yet the reader may find it harder to enjoy the outlaw tales of this raucous place after considering what led to its establishment – and that of much of the United States. Sure, there’s Wild Bill with his “dead man’s hand” of aces and eights, Calamity Jane tending selflessly to smallpox victims, and Sheriff Seth Bullock bringing order to the place before, in later life, becoming pals with Teddy Roosevelt. One feels sometimes that Cozzens himself – despite his deep knowledge – is rather too captivated with the dime-novel aspects of his yarn, referring repeatedly to Deadwood’s sex workers as “soiled doves” and sometimes straining – at least it felt that way to this reader – for positivity in depicting racial relations in the town.

David Milch, in his remarkable memoir Life’s Work, revealed that Deadwood was conceived when he pitched a show about ancient Rome, only to discover that HBO already had one in the works – and so he transposed his tale of greed and empire-building to the Black Hills. Furthermore, if you wonder why you should care about Deadwood – these days a bit of a grim tourist town – you may want to listen to a recent episode on Jonathan Freedland’s The Long View on Radio 4, in which he rightly compares the assault on Pahá Sápa with what is going on today in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: what we call “civilisation” depends on its wealth of copper, cobalt, diamonds, gold, manganese, and tantalum. Here we go again.

Deadwood by Peter Cozzens (Atlantic Books, £25). Order a copy at observershop.co.uk for £22.50. Delivery charges may apply.

Photographs by GraphicaArtis/Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy