“England fever”, the name given to a condition contracted by young Caribbean adults in the 1950s and 60s, refers to their overwhelming desire to leave their homelands for Britain.

The resulting swell of migration is satirised by the Jamaican folklorist Louise Bennett in her 1966 poem Colonization in Reverse. Its last stanza – “Wat a devilment a Englan! / Dem face war an brave de worse / But me wonderin how dem gwine stan / Colonizin in reverse” – captures that notion of Britain inadvertently reaping what it sowed as a colonial power.

This concept is central to Empire Without End, Imaobong Umoren’s capacious history of the four-century-long anglophone Caribbean connection with Britain.

Umoren sets out forcefully to chart the entanglement from the 1560s, when the buccaneer John Hawkins, with royal approval, captured and enslaved Africans to trade in the Spanish Americas, through to the Windrush scandal and 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. The book’s blunt tone is established in the introduction as Umoren recounts the racist judicial murder in June 1730 of 68-year-old Sally Bassett, who, after allegedly attempting to poison her white enslavers in Bermuda, was sentenced to death and burned alive.

Umoren’s thesis on the damage wrought by the “racial-caste hierarchy” (which some have called a pigmentocracy – a hierarchy based on race or skin colour) introduced by British colonialism is threaded through the book and is aided early on by Eric Williams, the first prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago, who wrote succinctly in Capitalism and Slavery (1944): “Slavery was not born of racism; rather, racism was the consequence of slavery.”

In unpicking the language and ideas the British employed to justify their brutal slave trade, Umoren’s prose is unfussy, clear and succinct. The academic rigour that underpins this history, which in recent years has been contested by those suffering “post-colonial melancholia” – a mourning of the loss of an imagined imperial greatness – is rewardingly readable.

Umoren reveals how anti-black racism in the 1870s was replaced by pseudoscientific racism, cynically adapted from Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. She also describes how, post-emancipation, the creation of an apprenticeship system under which the formerly enslaved received no wages – and subsequently indentureship – was slavery by another name. By 1917, close to 450,000 Indians had been shipped to the British Caribbean.

Such is the scale of Umoren’s ambition that her book is a marathon run as a sprint. There is no time to slow down to consider the complex personalities of those involved, such as Claudia Jones, the formidable chain-smoking communist founding spirit of the Notting Hill carnival; the wry aesthete and pioneering 18th-century “man of letters” Ignatius Sancho; or the vain and revolutionary Guyanese political leader Cheddi Jagan. Consequently, some of the drama and texture of this remarkable history is flattened on the way to honouring each staging post of the story.

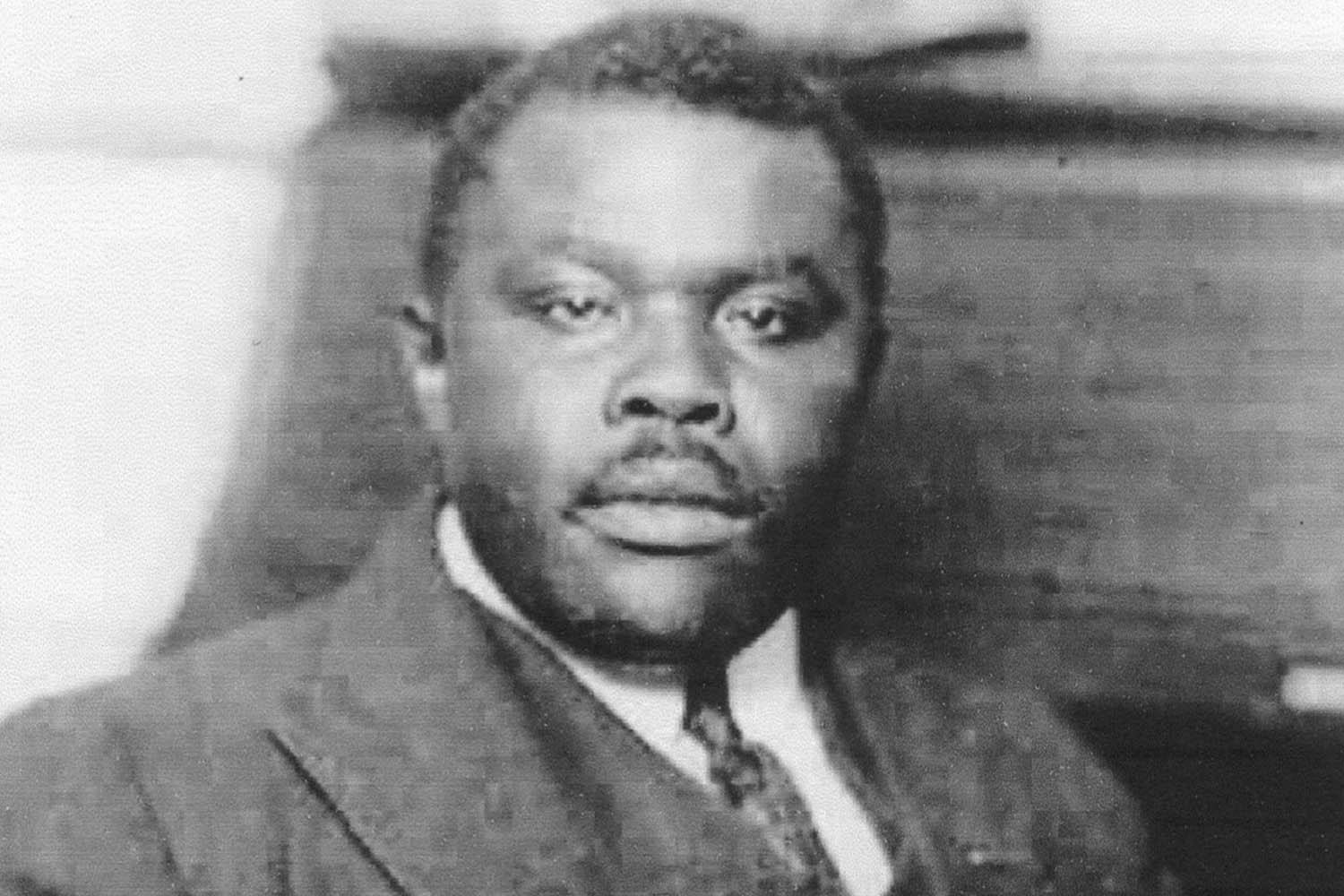

Even so, figures such as the flamboyant “Black Moses” Marcus Garvey and his extraordinary international mass movement, the Universal Negro Improvement Association, spark into life in this impressive 500-page-plus history. In just a couple of pages, Umoren demonstrates how Garvey spoke to the dreams and aspirations of the downtrodden in his attempt to unify black people worldwide and change the subservient mindset forged by British imperialism.

Before Empire Without End was published, Keir Starmer was criticised for a speech in which he suggested that Britain risks becoming an “island of strangers”, a phrase that echoes Enoch Powell’s infamous 1968 “rivers of blood” speech in which the Conservative politician warned that white Britons “found themselves made strangers in their own country”.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Powell’s views, which received significant support at the time, are a reminder, writes Umoren, that “Britain has never been on some sort of liberal march forward”.

Empire Without End is a valuable and accessible compendium, with Umoren skilfully distilling complicated histories. I’d have loved to have read such a book when I was a schoolboy, as a corrective to the vaporous British propaganda served up in classrooms in the 1970s. Ultimately, with forensic analysis, Umoren skewers British mendacity perfected over centuries.

One of the book’s strengths is its reminder that black people such as Garvey have always challenged the resurrection of that old colonial mindset in white and black people. Garvey’s words were passed on and echoed resoundingly in Bob Marley’s Redemption Song: “We are going to emancipate ourselves from mental slavery because whilst others might free the body, none but ourselves can free the mind.”

Empire Without End: A New History of Britain and the Caribbean by Imaobong Umoren is published by Fern Press (£25). Order a copy from observershop.co.uk for a special 20% launch offer (ends 11 June). Delivery charges may apply

Photograph by Getty