“A shilling life will give you all the facts… what acts/Made him the greatest figure of his day” wrote WH Auden in his poem Who’s Who. Swift Press is producing a who’s who of British prime ministers in a series that includes Alan Johnson’s Harold Wilson and Jason Cowley’s forthcoming take on Clement Attlee. The latest volume, Steve Richards’s Tony Blair, doesn’t quite give you all the facts and doesn’t quite comprehend what made its subject the greatest figure of his day.

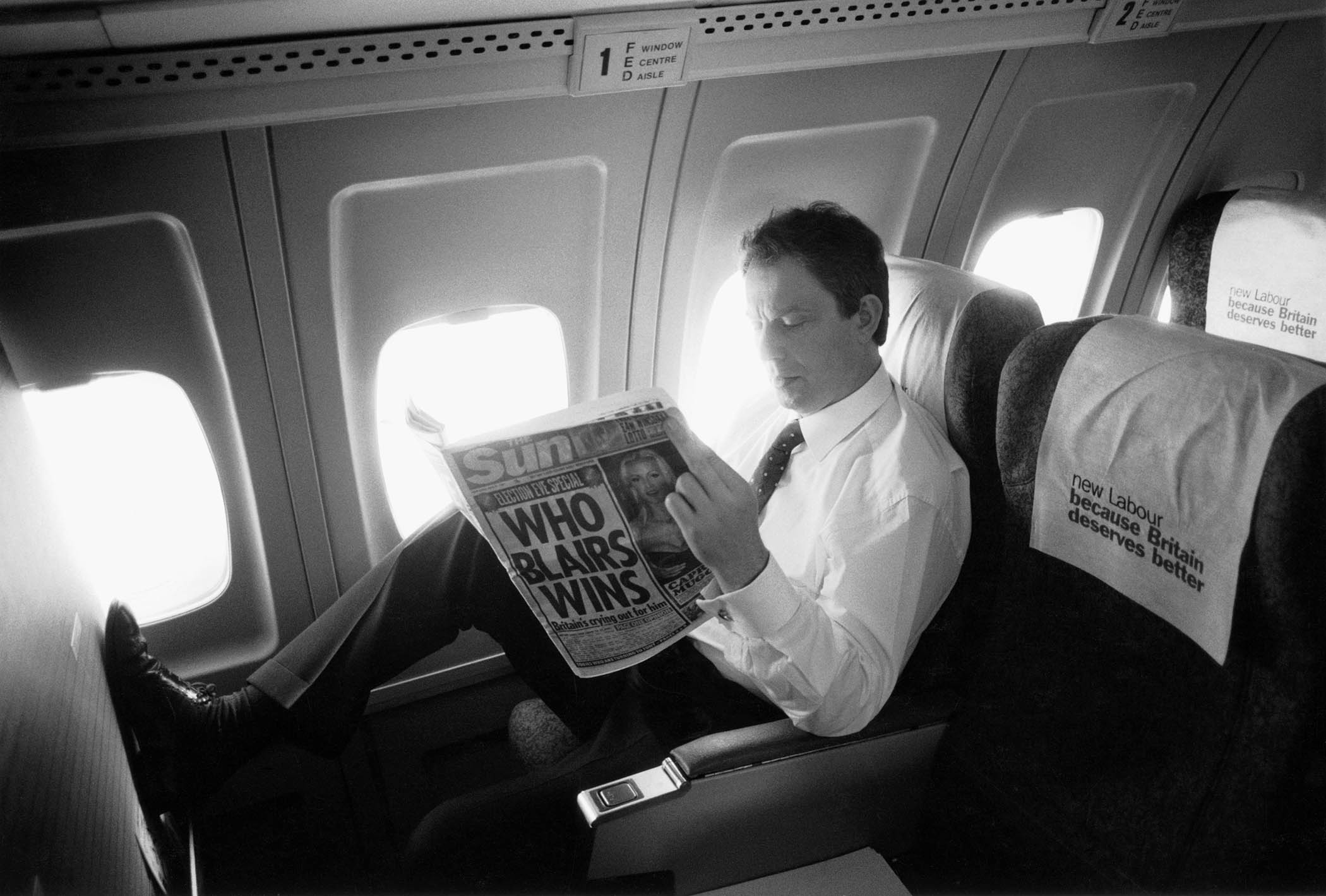

Auden’s lovely phrase, a shilling life, has acquired a new sense among the angry online left. There are plenty of critics who think the New Labour leader spent his life “shilling”, as they would put it, for Rupert Murdoch (the same people believe Blair, who has been appointed to President Trump’s board of worthies in Gaza, is surely the last man who can bring peace to the Middle East). Richards is far too wise a commentator for such a tendentious line, but he does have his own failing in this regard: there is too much in this book about the media, about how events played a day later for the broadcasters and editors. Richards might say that the Blair team were excessively concerned with the newspapers – indeed they were – but there is no need for the historian to emulate them.

This slim volume is, after all, a claim higher than journalism. The series is a kind of John Aubrey’s Brief Lives written by different people, or perhaps a modern, sceptical version of Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians. The subjects of Swift’s series are well known and often written about. The justification for another treatment must be an arresting new interpretation, or a summary of the scholarship. That latter option is not open to Richards; not enough time has elapsed for a significant body of historical work on Blair to have been completed. The book therefore has to offer a new vantage point.

There are certainly plenty of insights. Richards is good on the importance of Blair’s mesmeric skill as a speaker (“he made the cautious seem exciting”). It is true, too, that the 1997 Blair was all about being new, but he arrived with policy priorities that were rather old. One such old idea was devolution, and I shall henceforth adopt Richards’s point that Blair’s sop to Paddy Ashdown was a form of proportional representation for Scotland, which in time collapsed the Labour vote by opening an opportunity for the SNP.

The first chapter offers a glimpse of the book this might have been. Richards asks whether Blair was “a visionary, impatiently looking ahead, or a leader trapped by his past” and then concludes “he was both”. This strange commingling of expedient caution and evangelical mission is the way into Blair, and Richards is on to it. Some of Blair’s appeal – and here he does resemble Attlee and Wilson – lies in his conservative instincts. I wish Richards had followed this insight through and given us more on Blair’s attitudes towards antisocial behaviour and law and order. That would have taken us closer to the man than we get here.

Richards asks whether Blair was “a visionary, impatiently looking ahead, or a leader trapped by his past’

Richards asks whether Blair was “a visionary, impatiently looking ahead, or a leader trapped by his past’

Instead, we get more about the politics of policy than we do about its effects. There is not enough assessment of literacy and numeracy, the academies schools programme, the decline in waiting lists, the growth in pension provision (largely good) or the housing market or immigration (not so good). The British intervention in Kosovo is a case in point. Richards tells us that, for once, Gordon Brown was not on Blair’s back, that it suited Blair’s desire to be a war leader and that the Tories supported him. Well, yes, but what about the war itself?

The long chapter on Iraq is instructive. Richards is too smart to fall for the canard that Blair lied over Iraq, but the chapter rests on the commonplace observation that Blair was keen to stay close to the Americans. This is true, as far as it goes, but maybe it doesn’t go far enough. The more intriguing thing about Blair is that he agreed with George W Bush about the necessity of military action. In fact, Blair was more convinced than Bush that 9/11 had created a war of democrats against medievalists. Richards upbraids previous biographers for their accusation that Blair had become messianic over Iraq. That is, indeed, an overstatement, but he was certainly convinced. By the time of the invasion, Blair wasn’t just reacting to events from a position of diplomatic weakness, or under duress from the Sun.

One day, Blair will emerge as a radical conservative, a man who in part commanded and in part hoped to transcend his times. But perhaps it is too soon. We are not able to see Blair clearly yet.

Tony Blair by Steve Richard is published by Swift (£16.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £15.29. Delivery charges may apply

Philip Collins is a journalist, author and former speechwriter to Tony Blair. His books include Start Again: How We Can Fix Our Broken Politics (Fourth Estate)

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Photography by Getty Images