Not for the first time, Kevin Rowland could not stop. It was 1983, the height of Dexys Midnight Runners’ success, and the singer was fluffing take after take of an Italian television appearance by adopting a Benny Hill leer, pretending to lunge for the female presenter’s buttocks. He vowed that he would just do it normally – “and absolutely meant to” – but he could not. What, exactly, was going on here?

Uncomfortable to read, the unusual anecdote illuminates two of the currents that power Bless Me Father, the long-awaited autobiography of the maverick Dexys vocalist: his complex and destructive patterns of behaviour, and, contra to the comfy orthodoxies of the music memoir, a surprising impulse to write himself as the bad guy in his own life story.

There have been rumours of a Rowland book for at least a decade. In 2022, a memoir by the violinist Helen O’Hara became the first serious insider account of life in Dexys, while last year Rowland declined to be interviewed for Nige Tassell’s Searching For Dexys Midnight Runners. Recalling the 27-year gap between the third and fourth Dexys albums, Rowland devotees know not to hold their breath. But then came the announcement earlier this year of Bless Me Father, promising a “complicated” and “unvarnished” account of its teller.

Even in his earliest memories, Rowland was in trouble. The book’s title refers not just to his childhood clerical ambitions (he wondered, movingly, if he might become a “singing priest”), but the fraught paternal relationship that stalks the book, beginning to end. The second youngest of five children, Rowland was born in Wolverhampton in 1953 to Irish immigrant parents, who were part of the labour wave that made Irish people the largest incoming group to postwar Britain.

Dexys Midnight Runners in 1982, around the release of the band’s second album, Too-Rye-Ay. Rowland second from right.

In Rowland’s telling, his father, a building labourer, singled out his youngest son for blame, which became a self-fulfilling prophecy. “I got to almost quite like it when Dad hit me,” he writes. “Not the pain, but the attention.”

This meant that Rowland oscillated between chronic people-pleasing and intense private rebellion, and his account of the latter, as it escalated in his teens, is shocking. A childhood stealing habit becomes a compulsion. He fights, absconds from school, becomes a juvenile-court regular. In Soho, he loses his virginity to a sex worker, an experience he describes as clinical and depressing but nevertheless repeats an hour later. “I had wanted to get a lot wilder than I actually was,” he writes, in the stark, conversational style that typifies the book. “In truth, I was restraining myself.” Only a flash of good sense prevents him from following a grim audition to become a rent boy.

But while the era was not a good one for child safeguarding, it was a golden era for pop music and its attendant youth cults. Rowland is at his most vivid evoking a vanished world of junior mods gathered outside Wimpy bars, or the sounds of Jamaican reggae as it exploded across his native West Midlands and adopted north London.

Rowland credits the postwar welfare state with facilitating all of this experimentation. His own personal year zero came from watching the brilliant, forgotten mid-70s art-rock band Deaf School, whose theatricality and hot mess of styles informed the project Rowland was assembling.

In the 1980s, Dexys Midnight Runners were a far stranger proposition than their two No 1 singles might suggest. If anything links their three 1980s albums – distinct in both style and personnel – it is Ireland. The band’s debut album, 1980’s Searching for the Young Soul Rebels, lambasted Irish jokes and came in a sleeve depicting a Catholic boy forced from his home during civil unrest in 1970s Belfast (no small statement six years after the Birmingham pub bombings). Its successor, 1982’s Too-Rye-Ay, minted a Motown and Irish trad fusion that spawned Come On Eileen and became a primary influence on the Pogues (Rowland, we read, dismissed Shane MacGowan as “stage Irish” to his face, which he regrets.)

Rowland oscillated between chronic people-pleasing and intense private rebellion

Rowland oscillated between chronic people-pleasing and intense private rebellion

When that album’s success left him feeling empty and alienated – despite silencing critics, and briefly making him his father’s golden boy – he filled the void at first by pushing further into Irish republicanism. Rowland writes about attending Troops Out demos and buying socialist literature. Not coincidentally, these were also his father’s values. Next came 1985’s Don’t Stand Me Down, which tanked on release but has since been reappraised. Rowland, who otherwise gives little away about his creative output, said of it: “There was nothing on that album or its accords that would offend my parents,” framing it as both thrilling protest against British imperialism and longing paean to his upbringing.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Yet the dark bind of people-pleasing and rebellion persisted. It is possible to read Rowland’s account of, say, his addiction to kerb-crawling for sex workers at this time, or manoeuvring his brother out of a business deal, as recklessly candid. But in this, Rowland’s book is more compulsive and psychologically chewy than most music memoirs. Take his account of drug addiction. Ashamed and overwhelmed as Dexys collapses, Rowland is at first liberated by ecstasy’s arrival. But he becomes addicted to cocaine, which he uses like heroin, hitting private oblivion in a squalid bedsit. Rowland’s account of rock bottom is unsparing: his eventual sobriety, which he has sustained since 1993, provides the book’s long-withheld catharsis.

Since then, Rowland has successfully mined his complex life for autobiographical albums of soulful, retro pop like 2012’s comeback album One Day I’m Going to Soar (featuring some of his best work) or 2023’s The Feminine Divine. That album explored Rowland’s evolving attitudes to women, which form some of the most discomforting pages of Bless Me Father, as the teenager who jealously judges women becomes the adult who, in Rowland’s telling, attempts to “control and diminish” a kind and loving girlfriend. “It was disgusting behaviour,” he writes, and while his honesty should be commended, more on how he reached this conclusion would be welcome.

The past 30 years of Rowland’s life are summarised in the book’s final quarter, which tightens the focus on the relationship with his dad. Getting older, both father and son soften towards each another, and there is a lovely account of Rowland caring for his elderly parent following a stroke. Perhaps it was his dad’s death in 2021 that brought about the eventual release of this raw, startling but ultimately triumphant book.

Bless Me Father: A Life Story by Kevin Rowland is published by Ebury Spotlight (£25). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £22.50. Delivery charges may apply

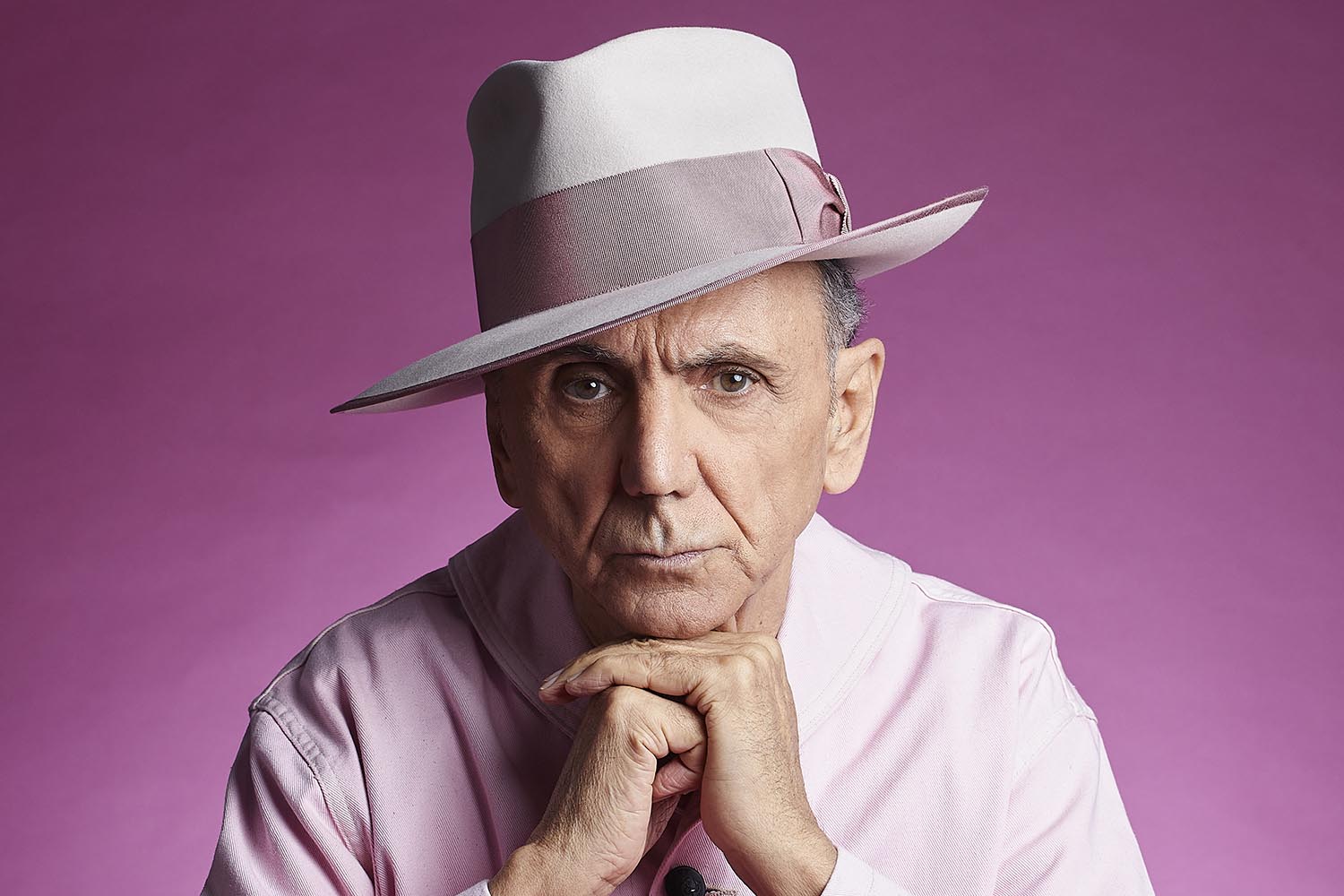

Photography by Nicky Johnston; Brian Cooke/Redferns