Job interviews are always nerve-racking, but the one I found most stressful involved sitting in a pub talking about jazz. The conversation flowed and yet I couldn’t relax because I wanted the job so much. It was to be editorial assistant to Margaret Busby, who was renowned for having set up a publishing company while still a student. I was already older than she had been at the time.

This was in the mid-1980s and Allison & Busby was approaching its 20th year, while Margaret had been lauded as Britain’s youngest and first Black female publisher. She has not stopped navigating all the expectations and assumptions that such achievements bring, as is clear from the new collection of her prose, Part of the Story: Writings from Half a Century, published next month. It opens with a piece she wrote for the New Statesman in 1966, skewering not only the racism she’d encountered since arriving at a British boarding school from Ghana, aged five, but clumsily performative demonstrations of non-racism as well. Margaret’s writing, like her thinking, is incisive, unflinching, sharply funny and exact.

In her prose and in person, Margaret neither shows off her expertise nor flaunts her achievements. Her lightness of presence is that of the consummate editor: fully focused and committed while working and thinking outwards. She understands the power of writing that is born out of personal imperative and framed by collective endeavour. She deflects attention and is quick to point out the activity going on around her, and the importance of sharing and passing on what you learn.

Having taken her O- and A-levels two years early, Margaret arrived at Bedford College, University of London, aged 17. She met Clive Allison at a party in 1965 and they decided that night that they would set up a publishing house. Within two years, they had. The press made much of “London’s swinging publishers”, and the unlikely duo of Clive, in a tweed waistcoat, and Margaret, with a large afro. They complemented each other well: Margaret’s incisiveness, judgment and editorial skills alongside Clive’s talents for persuasion, promotion and improvisation. They were committed, fearless and determined. As Margaret has said, “What we lacked in experience, we compensated for in ideals.”

I remember leaving the pub feeling as if I’d undergone a thorough interrogation while having a really good time. There was also an editorial test, which was just as subtle and rigorous as my interview. When I was given the job, I celebrated by buying an ancient, feeble motorbike that rattled me to Allison & Busby’s office in Soho. On my first day, I was so tremulous that I forgot how to brake and almost drove through the plate-glass window of the shop next door.

It did feel like stepping through a looking glass of sorts, finding myself in the land where books were actually made. There was, though, nothing magical about the office: two damp floors at the top of a bare, rickety staircase where I remember mould spores in lavish bloom. I was given a typewriter, a mug and a bar fire – and thought myself in heaven.

I would watch a tailor in the window opposite conjuring suits while learning that it is an editor’s job (rather like a tailor’s) to become invisible in the work, to make the writer more themselves and the book more itself, fine-tuning and then dissolving its machinery so that a reader doesn’t stop to think about how an effect was achieved, let alone about how a book was put together. Just as books don’t show how long they took to write or how hard they were to publish, their editing should be undetectable.

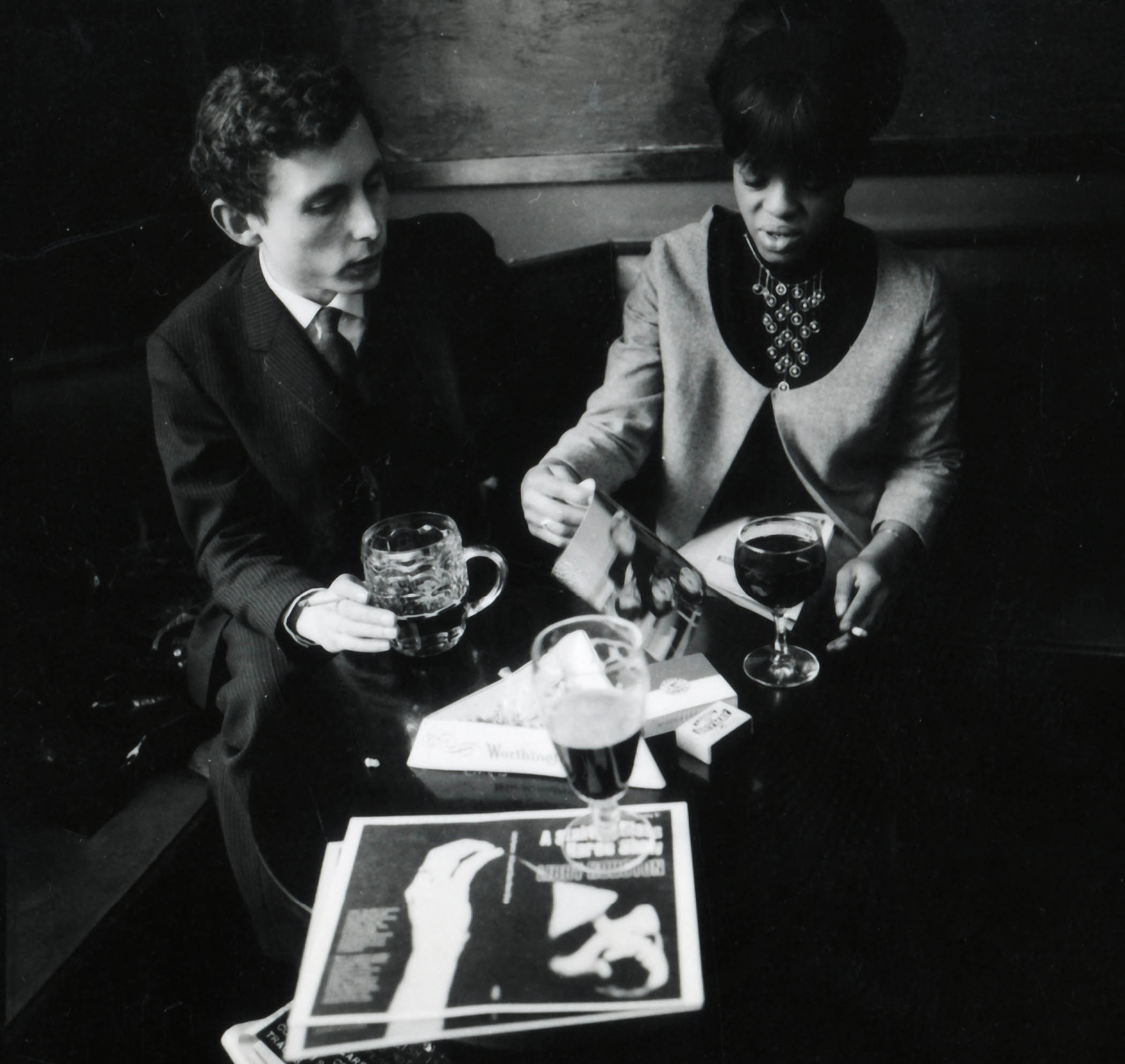

Above: Margaret Busby and Clive Allison enjoying a liquid lunch in 1967; main picture: Busby at work in 1971.

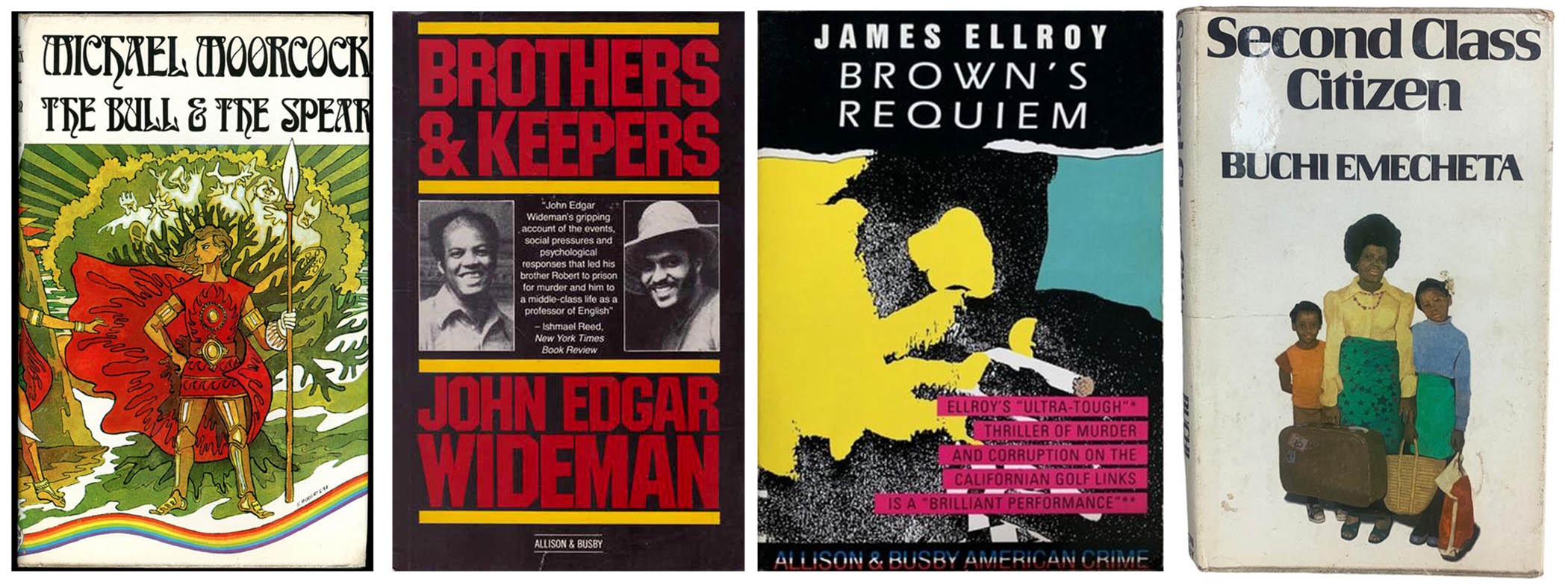

This was another aspect of Margaret’s expertise in presence and absence. She was determined to make underrepresented writers visible, to get important voices heard and key works read. She published the novelist and academic Buchi Emecheta’s Second Class Citizen in 1974. It is now a Penguin Modern Classic. The year that I joined the firm, we became the UK publisher of Brothers and Keepers, John Edgar Wideman’s memoir of his relationship with his brother, who was imprisoned for murder. I could be proofreading James Ellroy or a reissue of Jill Murphy’s The Worst Witch, now a children’s classic. I worked on titles by the poet Matthew Sweeney as well as the West Indian Marxist historian CLR James, whose books were then virtually unobtainable in Britain. No Allison & Busby author was like another, but they were all breaking new ground, raising questions that needed to be heard and finding new ways of doing so. The list also included Val Wilmer and Michèle Roberts, Alan Burns and Michael Moorcock (who I remember dropping in to pick up his post). Ahead of the times, the company would also launch a library of speculative fiction.

“Our reputation always far outstripped our means,” Margaret has said. When they took on a biography of Fela Kuti, the pioneer of Afrobeat, she paid part of the advance herself in the form of two new saxophones. Margaret and Clive once had lunch with Spike Milligan, who apparently decided not to offer them his memoir Adolf Hitler: My Part in His Downfall because Clive turned up in a three-piece suit, carrying a briefcase. That book, published by Michael Joseph in 1971, went on to sell more than 4m copies.

Margaret and Clive’s first idea had been to publish poetry not in the “expensive elitist hardback volumes in which it traditionally appeared, but as cheap paperbacks that even people like us could afford”. They worked to the strengths of each book rather than putting it through a process in which it was diluted, inside and out, into an overall house style. They put as much thought into getting their books to the readers as they did into editorial work, print and design. In the early days, this involved stopping people in the street and asking if they wanted to buy a copy.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Their first fiction title was The Spook Who Sat by the Door, a thriller by a Black American writer, Sam Greenlee. They offered the book for serialisation to The Observer, which sent it back, as the paper didn’t publish fiction, only for Margaret and Clive to send it again, saying they thought the paper was wrong and what a good book it was. This worked, and extracts duly appeared in The Observer magazine. The book was an international success and went on to become a cult film.

Publishing of this kind is never boring because it is always a speculation. You analyse and strategise but, in the end, you can only predict. The business runs on finding a balance between books that more or less adhere to your predictions, books that fail and the odd spectacular success. It’s not always possible to plan which will be which. The 1980s were a time of industrial breakdown, and economic boom and bust. Expectations hardened, costs surged and Allison & Busby’s finances were increasingly stretched. I remember being told: “We’re just going out to lunch. If the bailiffs come, don’t let them take anything.” Margaret has described Clive’s style as “seat of the pants”. He not only seemed to thrive in a crisis but to take a state of emergency for granted.

The publishing world was changing fast. Two years earlier, I’d been at the London College of Printing, being taught by men who had served six-year apprenticeships and who were now seeing technology take over from hot metal. These printers were exceptional teachers and committed to passing on what they knew. They taught us how to typeset, how to print and sew and bind and finish a book, using tools and machines that went back centuries and were soon to become obsolete. This wasn’t done as a statement against progress but because it was the best way for us to learn.

I recall being told: ‘We’re off to lunch. If the bailiffs come, don’t let them take anything’

I recall being told: ‘We’re off to lunch. If the bailiffs come, don’t let them take anything’

The space around the words was filled with furniture and you locked all this in place on the chase with quoins. Of course I relished the language of nuts and muttons (used to distinguish between the different widths of an “en” and an “em” space) and naming the parts. If you’ve physically had to fit words to a page, you understand all the decisions that need to be made and why they matter. I would swoon over a book of fonts the way someone else might over a car magazine, and would argue about the use of a slab versus a hairline serif or a ligature versus glyphs. I later took on a magazine editor for correcting the word “sanserif” to “sans serif” in my copy, assuming I was unaware of the French etymology. I spelled it the printers’ way. He also corrected the poet Paul Celan to Célan and Keats’s Madeline to Madeleine without bothering to check. It was a man’s world, as Margaret was well aware, and men just knew.

Once, a man hand-delivered a manuscript to the Soho office to Allison & Busby and I took it from him, politely saying that we would read it and respond as soon as we could. He snatched it back, asked me my name and then clarified the situation. “Listen. There is no ‘we’ in this. This is a submission to Clive Allison. Not to you or anyone else. There is no Lavinia here. Understand? Lavinia does not exist.” He came back a fortnight later and I was still there, happily existing. I’d even read his terrible book. He tried to bring himself to apologise for his earlier rudeness and asked me to help him get a response.

Clive hated making decisions. I learned to remain in his office when I needed an answer as he broke into a sweat and backed on to his radiator while staring at the phone on his desk, willing it to ring. I also learned not to leave the room out of politeness when it did. That day, I felt no need to hurry him, but he had heard about how I’d been treated, and when I said that the man had returned, offered a strongly worded rejection on the spot, which I conveyed with as little courtesy as I could get away with.

Margaret was wonderfully clear: she would see a problem and come up with the solution in the same moment. Allison & Busby was a glorious if precarious environment in which to work. The bailiffs gave up but at a time when independent publishing houses were being overwhelmed by big business, it teetered and tottered, and was bought out by WH Allen in 1987, having lasted for 20 years. Clive had negotiated a role for himself in the new setup and once invited me in. I remember walking heavily carpeted corporate corridors and finding him, looking even more panicked and trapped than he had back at Allison & Busby when I wouldn’t leave the room. He was desperate to get out of the building and to talk properly, in a pub. Clive went on to run a bookshop and died, aged 67, in 2011.

A selection of the classic books published by Allison & Busby.

When my job ended, I was 24 and three months’ pregnant. Six months after my daughter was born, Margaret offered me a job for the second time, as managing editor at the environmental publisher Earthscan, which she’d joined as editorial director. We were now in proper offices and part of an institute. It was my role to see the list through to publication, and finding Frantz Fanon or Han Suyin on my desk in the morning was an education. In the end, though, neither of us seemed to fit and we didn’t stay long.

Margaret went freelance and has remained so for more than 30 years, continuing to write, edit, review, broadcast, advocate, mentor and campaign. Currently president of English PEN, she is renowned, celebrated and invited the world over. In 1992, she published the landmark Daughters of Africa: An International Anthology of Words and Writings by Women of African Descent from the Ancient Egyptian to the Present. Not content with having brought all those voices to the fore, she did it again with New Daughters of Africa in 2019, and set up an award covering fees and accommodation for an African woman student. The first recipient, Idza Luhumyo, went on to win the Caine prize for African writing. The list of awards that Margaret has judged, the reviews, obituaries and introductions she has written, the keynote addresses she has given and the festivals and conferences at which she has spoken is endless. I know no one who has worked so consistently to champion not only the work of others but also cultural change.

At Allison & Busby, I once burst into tears and admitted that I’d stayed up all night reproofing a book after something had gone wrong at the typesetter’s, but hadn’t managed to finish. Margaret consoled me by saying firmly that I should have left it for the morning, that everything would be all right and that, after all, “they are only books”. I felt reassured, even though I knew that books were never only books and that Margaret’s commitment to making them possible and available would be full time and lifelong. In that moment, she had put her snivelling assistant first and I was extremely grateful.

Writing in 1985, she quoted her friend and fellow editor Toni Morrison, but could have been speaking for herself: “What I really want to do... is to make it possible for someone else to do the same things.” She has and she does and she will.

Part of the Story: Writings from Half a Century by Margaret Busby is published by Hamish Hamilton on 26 March (£22). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £19.80. Delivery charges may apply

Photographs by Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images, Courtesy of Margaret Busby