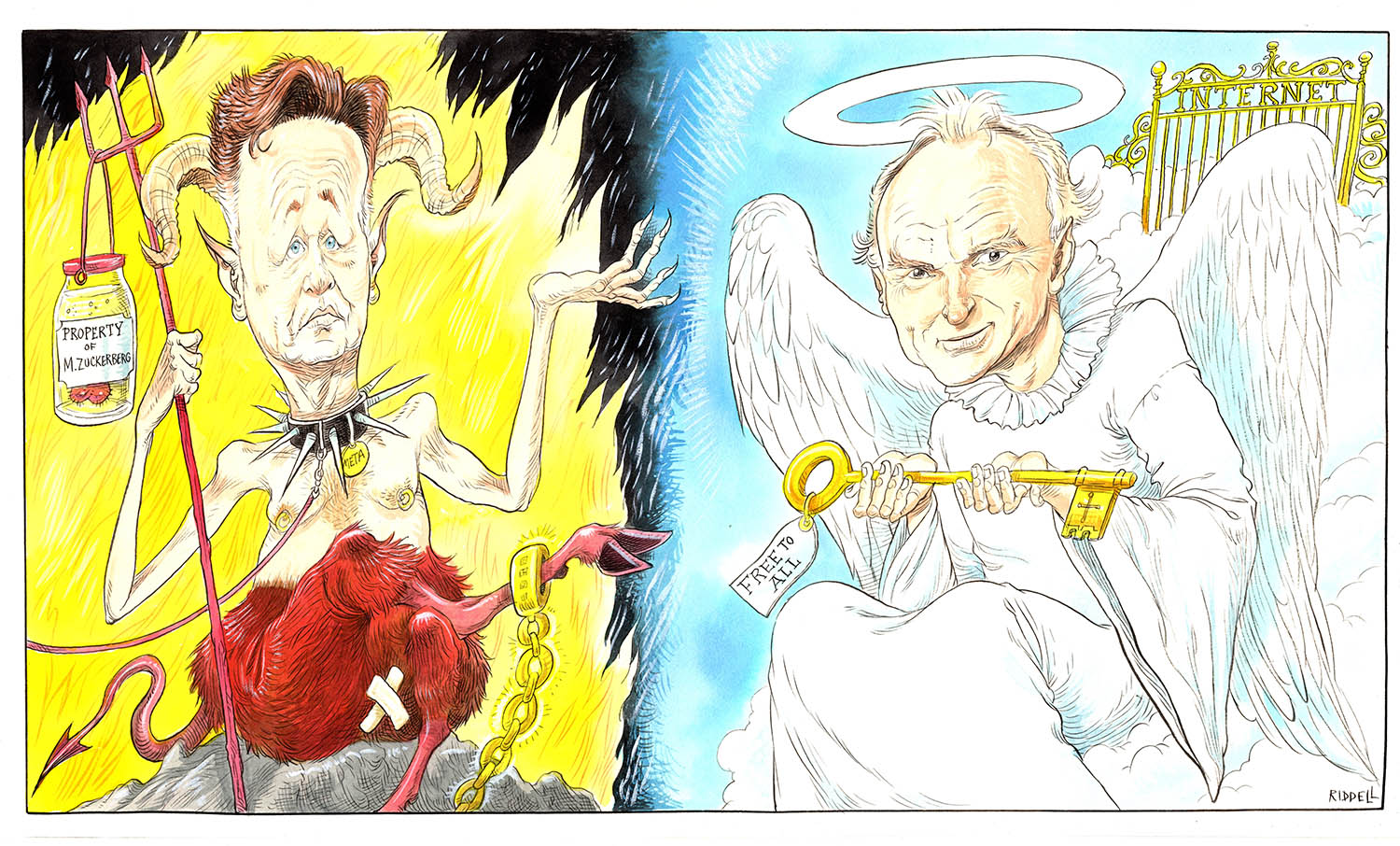

Illustration by Chris Riddell

Nick Clegg, former deputy prime minister of the UK, a former vice-president at Facebook, has returned from his time in Silicon Valley with a book titled How to Save the Internet. It’s a strange mixture of reminiscences, some of them hilarious – like the time Nadine Dorries called him, demanding he take down tweets by Vladimir Putin, and he had to explain that Twitter was a different company to Facebook – and an attempt at big-picture thinking.

There is useful information here. Studded throughout, without fanfare, are good analyses of the political situation around technology, and suggestions – such as that the EU needs to unify its digital regulations so that “a small tech startup” in a European city doesn’t have to navigate 27 different sets of laws and regulatory bodies.

But Clegg knows what the problem is. Early on, he holds his hands up: “You may well feel the arguments I make in this book are an attempt to defend the honour of my former corporate paymasters.” Indeed. If you want to read 300-odd pages about how poor Meta, one of the most powerful companies on earth, has been unfairly criticised and everyone should be nicer to it, well, this is the book for you.

Clegg apparently believes that the “techlash” – a term for the growing suspicion and fear of the power and influence of large tech companies – is something we all just need to get over. To those of us who point to social media and its algorithms as a vector for polarisation, for mental health problems, for anger and distress, Clegg says instead that we should be looking at “economic inequality, systemic racism… the Covid-19 epidemic… the opioid epidemic or the debt trap”. Well, yes. We should be looking at those things. We should also be looking at technology and at the people at the head of organisations which now present themselves as a homepage for the internet. Like Facebook.

Disingenuous politicians’ arguments such as this run through the book, as well as an absolute unwillingness to confront difficult questions head-on. If newspapers are suspicious of social media, that’s because “the new business models… have upended their own”. If analysts want to talk about the specific way that social media shapes our thinking, that’s nonsense, because “technologies aren’t inherently good or bad”. But not being inherently good or bad doesn’t mean they don’t have any inherent qualities. Social media works best if a lot of people are on the same site, which creates monopolies. And monopolies can treat their customers badly because they have nowhere else to go.

Meta is currently being examined by an antitrust case in the US, which challenges whether it should have been allowed to buy Instagram and WhatsApp. Spoiler: it should not. The reason we have competition laws is that capitalism only works well if consumers have a choice. Clegg declares that the antitrust approach “completely ignores the benefits users gain from large network effects”. This is wildly misleading. There’s a large network effect within a single social media platform: it’s great for me if all my friends are on the same social network that I use. But there’s no benefit to me as a user if Meta owns Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp too; like most people, I use these services independently of each other. The benefit is only to Meta: it gets all the data and ad revenue.

Clegg suggests that we could in future face a fracturing of the internet into different jurisdictions. This is a real threat. For example, America embraces a free-speech absolutism; many voices in America would like to see an end to British laws against incitement of racial hatred. Because so many big technology companies are based in the US, they instinctively, as well as financially, favour a laissez-faire policy in which it’s not down to tech companies to monitor or take any responsibility for the hateful words they’re publishing. This and other policy disagreements could end up meaning that the internet is vastly different depending on which country it’s accessed from – with all the problems for trade, banking and seamless communication that Clegg suggests.

Related articles:

Clegg was working closely – and, at one point, even mixed martial arts fighting – alongside Mark Zuckerberg

Clegg was working closely – and, at one point, even mixed martial arts fighting – alongside Mark Zuckerberg

But this argument would play much better coming from Meta’s former vice-president of global affairs and communication if Facebook itself hadn’t contributed to the development of the fractured internet. Notably, in 2015, the company launched a controversial service in India called Free Basics, which was deliberately designed to limit the internet available to millions of users to a paltry handful of sites all chosen by Facebook. The fallout from that debacle is very well described in Sarah Wynn-Williams’s Careless People, a book about Facebook that’s well worth reading.

Wynn-Williams also gives an honest account of the horrors of Facebook’s approach to Myanmar. She describes how she had to wait for one Burmese-speaking contractor in Dublin to get home from a restaurant and find his laptop so that he could review posts that were already promoting violence and sparking the murders of Rohingya Muslims. This is not how a responsible company making more than $100bn of revenue a year should operate. Clegg devotes two paragraphs to Myanmar, acknowledging “serious mistakes” but explaining that actually it is technically very difficult to translate Burmese.

There is a buried story in How to Save the Internet. Clegg mentions that in 2018, when he was considering taking the job at Facebook, his eldest son, still school-age, was recovering from cancer. Clegg had been ousted in an election, dismayed by Brexit, and was offered a high-paying job in a new industry in sunny California. A fresh start for the family after the terrible ordeal of cancer. I can understand why he took the job. I can understand why he left Meta after Donald Trump was elected. What I can’t understand is why he has written this book.

Fundamentally, this is a question about values. Clegg calls for laws that may bind technology companies’ hands and make them do the right thing. But given that he was working closely – and, at one point, even MMA (mixed martial arts) fighting – alongside Mark Zuckerberg, you wonder why he was never able to convince senior Facebook leadership that they could in fact choose to treat its users with dignity and respect; make the platform a world leader in encouraging openness and fair-dealing; and decide that it had enough money to do something good for the world. That Clegg failed to convince Zuckerberg of any of this makes his story almost a tragedy: he is apparently constantly sitting at the right hand of the powerful, unable to influence them. Perhaps he just likes the view from the seat next to the top chair.

Compared with Clegg’s obfuscation and political manoeuvring, Tim Berners-Lee’s memoir, This Is for Everyone, is a cool breath of air in an overheated room. Berners-Lee literally invented the world wide web, and he’s clear-eyed about the benefits and the dangers. The book is a reminiscence about how the web came into being, and contains some very sharp thinking about what we need to do now.

The personality that comes through is charming, clever, self-effacing, interesting and thoughtful about his creation. Berners-Lee was the son of two mathematicians who both worked on the Ferranti Mark I, the world’s first commercially available computer. He grew up in a house where inventing was a normal part of life. Charming photographs and diagrams illustrate various parts of Berners-Lee’s life, including a circular calendar his mother invented that became a record of each year. As a boy, already thinking about how to get people communicating, he sorted through a bag of factory-reject transistors to find the ones that worked, and built an intercom that linked the upper and lower floors of his family’s London home.

Berners-Lee is part of what he describes as a particularly blessed generation technologically. He makes a convincing case that being born in 1955 – like Bill Gates and Steve Jobs – meant that he and his peers had “a magic carpet ride through the wave of tech”, with new hardware becoming available precisely when they needed it.

After gaining a degree in physics at Oxford, Berners-Lee worked in Switzerland at Cern – the European Organisation for Nuclear Research – where he had an idea about how documents created by different teams could be made accessible to everyone. In March 1989, he wrote a memo about how hypertext documents could be combined with connected computers to create a useful sharing system. No one was interested. He sent it around again in 1990, and the moment was suddenly right. The book traces how the early web developed: the creation of the first browsers and the tussles for control of the sector, particularly between Marc Andreessen’s Netscape and Gates’s Internet Explorer.

Perhaps what is most extraordinary about Berners-Lee’s career is that he never sought to own or profit from his invention. And he managed to convince his bosses at Cern to do the right thing too. By 1993, he realised that “the only way forward… was to donate the intellectual property behind the web to the public domain… For the web to succeed it had to be free.” There were arguments against it: the web was a brilliant European invention that Europe could use as leverage to compete technologically against the US. But for Berners-Lee, the critical thing was the public good. On 30 April 1993, the director of Cern signed a document saying “Cern relinquishes all intellectual property rights” to the code that underlies the web.

Perhaps what is most extraordinary about Berners-Lee’s career is that he never sought to own or profit from his invention

Perhaps what is most extraordinary about Berners-Lee’s career is that he never sought to own or profit from his invention

Berners-Lee is delighted by the joys of the modern internet, the collaborations, the easy ability to see manuscripts and beautiful objects that were once locked away. But he’s also robust on its problems and their causes. He understands that just because technology isn’t, as Clegg would say, “inherently good or bad”, it still has tendencies and influences. Berners-Lee correctly compares the internet to the printing press, which “allowed the distribution of a great number of new ideas” but also led to “political and social unrest”. The sum of not inherently good or bad isn’t zero. Berners-Lee has become “disillusioned with Facebook”, with its way of using data to target its users, violating their privacy. He is right that social media such as Twitter/X and Facebook are “optimising for engagement, rather than enjoyment… showing nastier and nastier stuff – ‘rage bait’, basically”.

His recommendations for the 21st-century world wide web are also extremely clear and sensible. He wants social media designed “to maximise the joy people [get] out of discussing things with others, rather than feeding off hatred”. He suggests that social media algorithms could be specifically created for teenagers and anyone feeling vulnerable, steering them toward healthier content.

The book ends with a simple, powerful list of recommendations for governments, companies and citizens to create a better web. The last one is for all of us: “Fight for the web,” Berners-Lee says. He is 70 now, and we’re not going to have his leadership for ever. This book is like a letter from Johannes Gutenberg about what he hoped the printing press could be; we’d do well to take it to heart.

You finish reading This Is for Everyone wishing that somehow the Cleggs and Zuckerbergs of this world would vanish, and that Facebook and the rest of social media could be run by Berners-Lee – who would immediately give them away to the users, because he really does believe that this is for everyone.

How to Save the Internet: The Threat to Global Connection in the Age of AI and Political Conflict (Bodley Head, £25) by Nick Clegg and This Is for Everyone (Macmillan, £25) by Tim Berners-Lee are both available from The Observer Shop with a 10% discount.

Don’t Burn Anyone at the Stake Today by Naomi Alderman (Penguin Books Ltd, £16.99). Order a copy at observershop.co.uk for £16.99. Delivery charges may apply.

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy