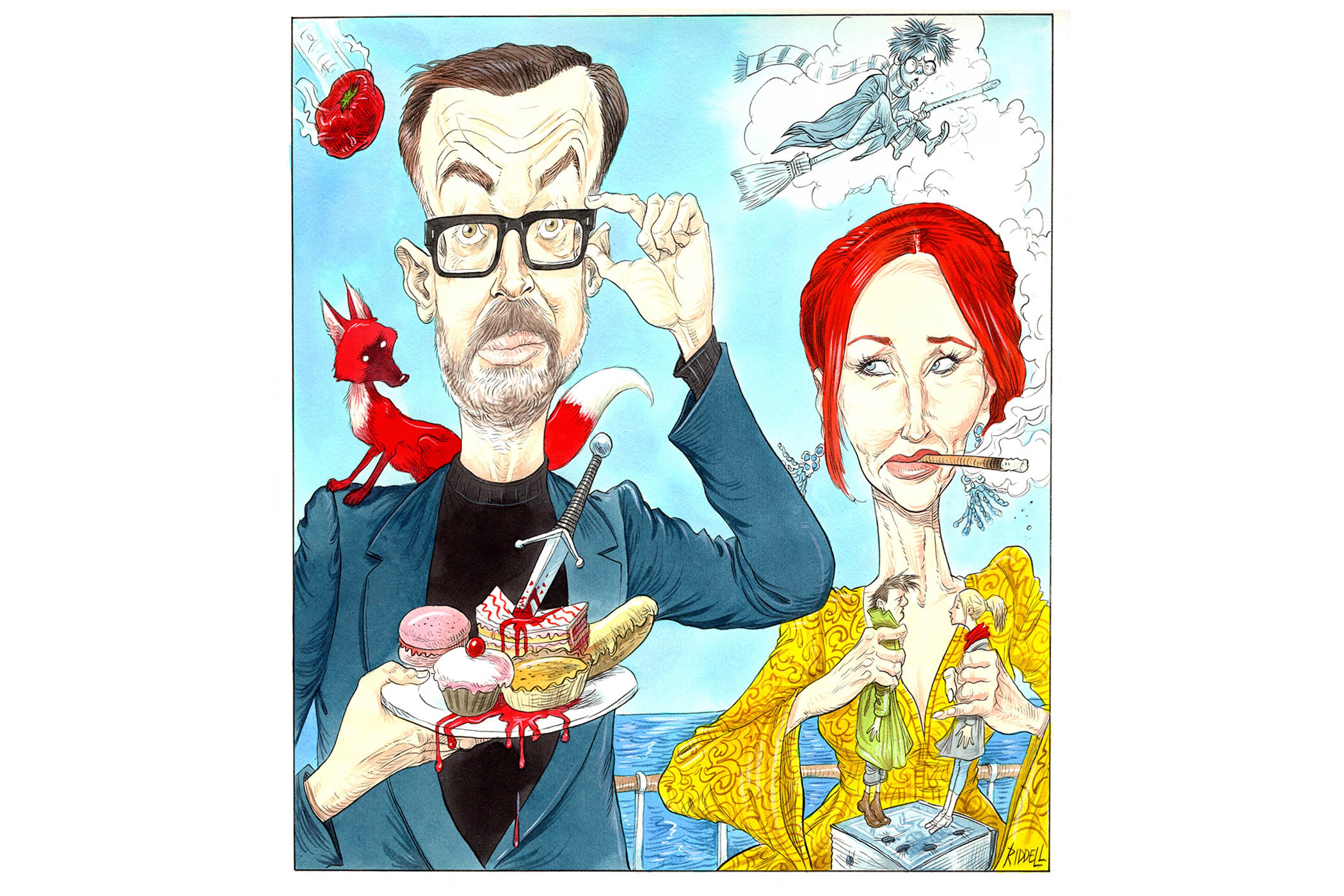

Illustration by Chris Riddell

Why bother with the Booker? Here we have the novels the nation actually wants to buy and read this autumn.

On its publication on 2 September, The Hallmarked Man, the eighth Strike novel by JK Rowling under her pseudonym Robert Galbraith, went straight to the top of the bestseller lists with 53,207 copies bought in the first week. Never mind how many Harry Potter books Rowling has sold (more than 600m worldwide); her private detective Cormoran Strike is doing pretty well for her too (some 20m, so far).

But Strike will surely be knocked off his perch this week by the fifth novel in Richard Osman’s Thursday Murder Club series, The Impossible Fortune. The previous instalment, The Last Devil to Die, became the fastest-selling adult fiction hardback by a British author, shifting 146,919 copies in its first week. Osman has broken records with all four books since his debut sold a million in its first year: total worldwide sales of the four books have topped 15m already, according to his publishers. The expensively produced, Downton Abbey-aspirant Netflix film may be a bit dozy even for fans – “about as thrilling as a pair of support tights”, said Wendy Ide in The Observer – but Osman’s commitment to proper product continuity cannot be faulted. As a successful deviser of TV shows, he knows its importance. “My whole career is formats, really,” he told one interviewer. “And the real key with the format is to make it familiar, but look different.”

So here’s the same deal again, minimally altered. The Cooper’s Chase gang is back: formidable Elizabeth, blokey Ron, fastidious Ibrahim and lovable Joyce. So are all the others: hunky Bogdan, obliging Donna, friendly drug lord Connie. And there’s a plethora of crime in the little town of Fairhaven once more. Connie is coaching an apprentice thief, Tia. Ron’s daughter, Suzi, has broken up with her villainous husband, Danny, who’s out to bump off both her and her brother, Jason. And Nick Silver, the best man at the wedding of Joyce’s daughter, Joanna, has disappeared after saying someone has tried to kill him with a car bomb. Could it be his business partner Holly Lewis, criminal contact Davey Noakes, or perhaps bankrupt peer Lord Townes? There’s a cryptocurrency fortune there to be taken, if only a code can be cracked. “A drug dealer, a lord and a car bomb, dear? It seems that I’m needed again,” says Elizabeth, addressing the spirit of her late husband, dementia sufferer Stephen, a sweetheart much missed after taking his own life in the previous book.

Osman adroitly weaves all these plots together without confusing or exhausting the reader – quite the feat. It works because he has simplified his style so effectively, using short chapters, short sentences with few subordinate clauses, laid out in microparagraphs, and a lot of dialogue (nearly all of it in very short phrases, too).

Osman reaches audiences other authors do not because he truly shares their world

Osman reaches audiences other authors do not because he truly shares their world

It’s often said that the great inspiration of cosy crime is Miss Marple, but Osman is more obviously influenced by Enid Blyton and The Famous Five, as he has cheerfully acknowledged. Age-inappropriate amateur detectives, two boys, two girls, plus a dog, always true to type, taking on hardened criminals, while being assiduously served up drinks and snacks by their author in easily understood prose: that’s the ticket.

Most of the story is delivered in a chatty third-person present tense, the most user-friendly of narrative modes, almost like turning on the telly (“Ibrahim brings in a tray with three mugs on it,” etc). For extra ease of understanding, we are often told, in the same voice, what the characters are thinking as well as doing. To vary the tone a little, Joyce takes over the story now and then, in the first person, with lots of Alan Bennett-style homely incongruities, but in the same present tense: “I’m watching Flog It! – it’s about antiques before you get any ideas – but I’m not really concentrating…” Neither are we. Comprehension is never difficult; the reader has no work to do. Critically, the cosiness is not just in the setting but in the delivery too.

Osman’s remarkable mother, Brenda Wright, has been the sharpest critic of his prose, observing that “it would be a great book for foreigners if they’re learning the English language”. This is treasurable, because it was Wright who provided the inspiration for the series, after Osman bought her a home in the luxury retirement village of St George’s Park in the South Downs. She is right, but she could have gone further. These novels are readily enjoyable by people who usually don’t find reading whole books in any language appealing or easy (even when printed in such a big typeface) but have watched a lot of TV.

Being a celebrity may have helped Osman to get his career as a novelist under way, and he may be part of a whole genre of cosy crime kickstarted by the pandemic. But these books could not successfully have been written down from above; Osman reaches audiences other authors do not because he truly shares their world. Over and over, he has told interviewers: “I’m genuinely, determinedly and proudly middle-brow.” He means it – and he wants to entertain people like himself.

The basic joke of The Thursday Murder Club remains, of course, a juxtaposition of worlds, the comfy and the criminal. Concern over the safe and familiar is set against flippancy about life and death. Flapjacks always matter, car bombs only in passing: Osman neatly brings the two together here in one explosive scene.

You might think there would be diminishing returns from seeing the gang vanquish the villains once more, hearing again about so many cakes and cups of tea. On the contrary. In series novels, as in all soaps, familiarity is altogether desirable. It makes for a warm glow, a feeling of belonging and companionship. Up to a point, anyway. (As Samuel Beckett wrote, “The lower the order of mental activity, the better the company. Up to a point.”)

Robert Galbraith stretches the point. Some series novels, such as Simenon’s marvellous Maigret books, belong to a consistent world but don’t follow on from one another, so they can be read singly and in any order. The Strike novels are not like this. They are one work and that work has now reached monstrous proportions: eight volumes so far (there were only seven Harry Potters), totalling 5,926 pages. The whole of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time in the Everyman edition runs to only 3,152 pages. This volume alone, not even one of the longest Galbraiths, is a little bit longer than most editions of Anna Karenina. On her website, Rowling promises that volumes nine and 10 are “all plotted” already. She has colour-coded spreadsheets, she says, so she can keep track of where she’s going.

It’s not the procedural component that really interests Rowling, but rather the unconsummated romance between Strike and Robin

It’s not the procedural component that really interests Rowling, but rather the unconsummated romance between Strike and Robin

The main crime investigation here, a locked-room mystery, is skilfully organised. A mutilated corpse, without hands or eyes, has been found in the vault of a dealer in masonic silverware. The police have lazily identified the body as that of a small-time villain and lost interest, but Strike is commissioned to investigate further by a wealthy woman who positively hopes the body is that of her lover, preferring to believe he was murdered than that he abandoned her when she became pregnant. Strike and Robin, his business partner (and great undeclared love), are soon on the trail of several missing men who might be candidates for the corpse, ultimately leading them to uncover horrific sex crimes. Not many men are nice, chez Galbraith. “Men perennially underestimate how many of their fellow men are perverts and predators,” Robin tells Strike, as well she might, given her backstory.

As meticulous as it might be, it’s not the procedural component that really interests Rowling. It’s the unconsummated romance between Strike and Robin, teetering on fulfilment now for nearly 6,000 plodding pages. Will Strike open his heart to Robin at last? He needs only to say the word. “The dynamic between them is, I think, the thing that keeps people reading and it’s certainly the thing that keeps me writing,” says Rowling, herself clearly in love with them both. Many readers may, by this point, be a couple of thousand pages beyond caring.

The Impossible Fortune by Richard Osman is published by Viking (£22) and The Hallmarked Man by Robert Galbraith (JK Rowling) is published by Sphere (£30). Order from The Observer Shop to receive a 10% discount. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy