You know those people who like to claim that reading novels increases empathy? Those people aren’t talking about the novels of Jean-Patrick Manchette. Short, bleak and extremely violent, Manchette’s books took the French crime thriller – moribund and rightwing by the end of the 1960s – and injected it with leftist energy and vitriol.

Manchette, born in Marseilles in 1942 and raised in Paris, spent his 1960s as a student communist then a situationist. He wrote for money, producing screenplays and film novelisations. He also translated books by crime writers including Donald Westlake. Both strands of Westlake’s output, which alternated between hard-boiled thrillers and more comic capers, feed into the 10 novels Manchette published between 1971 and 1981. He grew disillusioned with fiction after that, but was writing the first novel in a four-book sequence when he died of lung cancer in 1995, aged 52.

The Nada group that gives this, Manchette’s fourth novel, its title, is a ragged assortment of revolutionaries with various types of chequered past. To draw attention to their cause, they plan to kidnap the US ambassador to France. The first 50 pages are devoted to the formulation of the plan and its final preparations, the rest to its spectacular unravelling.

This isn’t a simple cops versus criminals plot, though. A major turn in the action occurs due to a feud between various factions of the French security services, the SDECE and the SAC. “Few thrillers have been stuffed with quite as many acronyms as this one,” writes Lucy Sante in her introduction to the New York Review Books edition (sadly no equivalent is included in this Vintage Classics version, translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith). As for morals, neither the forces of the state nor the terrorists have more than a very slippery hold on those, although at least one Nada member will have an epiphany about his methodology before the final trigger is pulled.

Manchette wastes none of his readers’ time, one short chapter after another driving the book relentlessly to its end

Manchette wastes none of his readers’ time, one short chapter after another driving the book relentlessly to its end

The world, as Manchette paints it, is grimy and sordid. Plans only ever go south. The apartments smell of stale smoke and dirty feet. There are ants in the sugar bowls, and the cassoulet – eaten from the can – is cold and greasy. The book’s sole sexual encounter ends in disappointment: “It’s the stress,” the woman says. “Things will go better tomorrow.” The man isn’t so hopeful. “Tomorrow,” he thinks, “they would be dead.”

Manchette’s novel shows undeniable signs of ageing. Knocking people unconscious with a karate chop to the neck feels very early 1970s, not to say very Austin Powers. More significantly, the book’s sexual politics are as disastrous as the kidnapping. Cash, the one female member of the gang (“I’m not a girl, I’m a whore”) only really exists for the crumpled antihero Épaulard to lust after – bizarrely, he compares her behind to that of “a young boxer dog” – and to deploy a chaos-making burst of machine-gun fire at the book’s crisis point. These leftists – probably realistically, it must be said – either haven’t heard about, or aren’t impressed by, second-wave feminism.

Whatever one’s level of distaste for this aspect of the book, it remains incredibly exciting to read. Manchette wastes none of his readers’ time, one short chapter after another driving the book relentlessly to its end. Along the way, like any critic of capitalism, he pays attention to the brands of cigarette his characters smoke, the models of car they drive, the makes of gun they shoot.

He knows their positions on the political spectrum, too, and the way these gradations manifest between comrades, whether anarchist, libertarian communist or Maoist (actually, every member of the gang thinks Maoists are idiots). And he possesses the best of all traits in a thriller writer: recondite knowledge that, whether rightly or not, the reader trusts absolutely, as when Épaulard recommends skipping a meal before the kidnapping. “The trick,” he says, “is to have an empty stomach in case of a gut shot.”

Related articles:

Nada by Jean-Patrick Manchette, translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, is published by Vintage Classics (£9.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £8.99. Delivery charges may apply

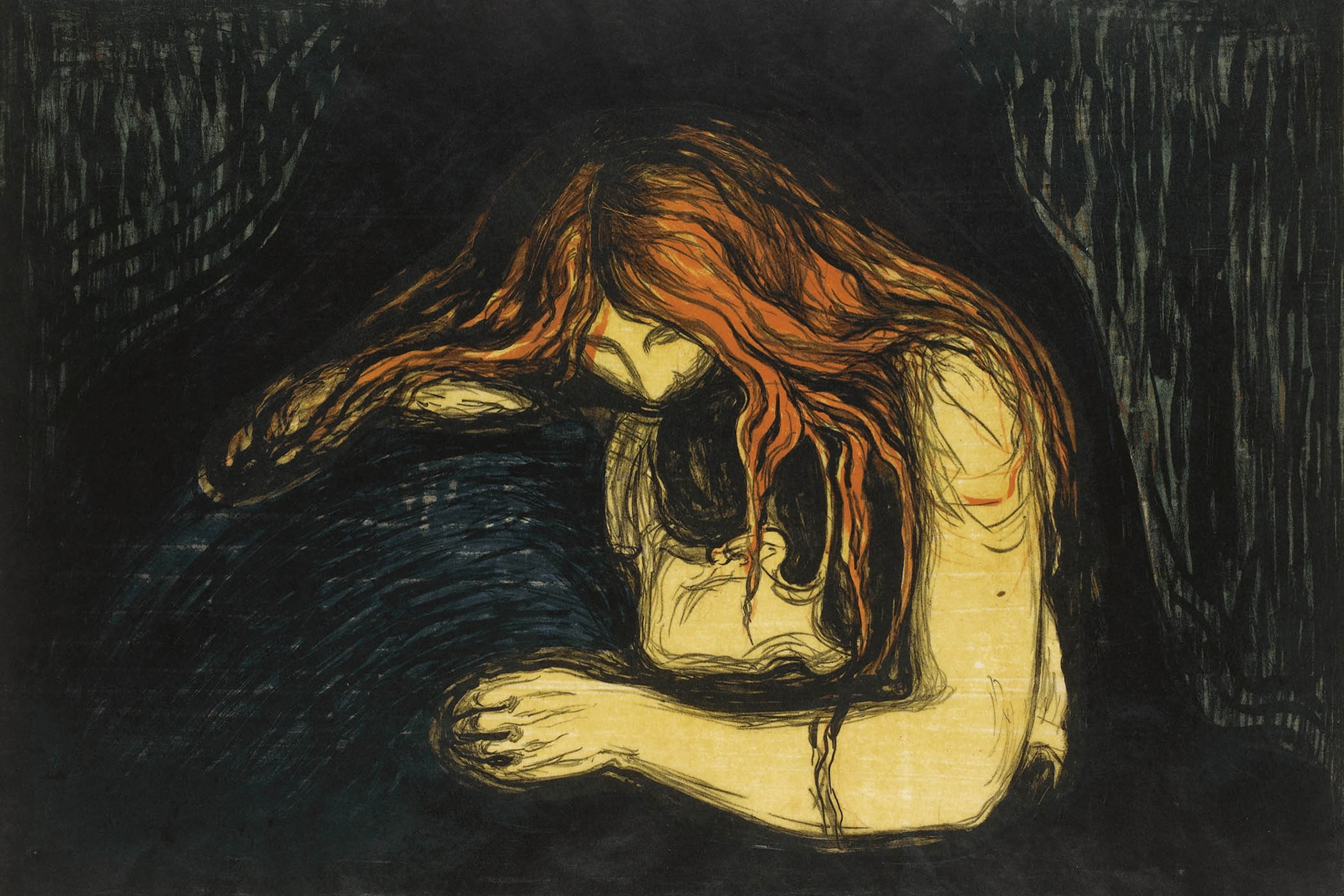

Illustration by Penguin Books

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy