Who are the true pioneers of nature poetry? Before William Wordsworth’s imagination had wandered, lonely as a cloud, and before John Keats’s nib had quivered with notions about nightingales, a Black woman named Phillis Wheatley was circulating a treasury of nature-inspired verse in London.

Wheatley was born in 1753, then kidnapped and sold into slavery (from Senegal or Gambia) at around seven years old. Deemed too “frail” to work in the colonies, she was shipped to Boston, Massachusetts, named after the vessel that transported her (the Phillis) and purchased “for a trifle” in 1761 by John Wheatley, a wealthy tailor, and his wife Susanna, who was “in want of a domestic”. After they caught the girl “endeavouring to make letters upon the wall with a piece of chalk or charcoal”, the Wheatleys, probably involving their son Nathaniel and daughter Mary, began 16 months of tuition. During this period, Wheatley “attained the English Language, to which she was an utter Stranger before”, according to John, “to the great Astonishment of all who heard her”. She read John Milton, Alexander Pope, Virgil, Ovid, Terence and Homer. And, “as soon as she could read well, she began to make Rhymes”, recalled Charles Stratford, a descendant of one of Susanna Wheatley’s relatives. Or, in the words of Wheatley herself: “Seeing others write made me esteem it a valuable art.”

Anti-literacy laws prohibited enslaved and free Black people to read and write. But, as Wheatley insisted, she “was treated by her [Susanna] more like a child than her Servant ... I presently became a sharer in her most tender affections”. In 1772, Susanna placed adverts in Boston newspapers for subscribers to fund the costs of printing a collection of Wheatley’s poetry – the Kickstarter of the day. When support faltered, Susanna wrote to Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon. This 18th-century evangelical influencer arranged for Wheatley to be published in London – where abolitionist networks were more receptive to the idea of a Black poet – by a bookseller named Archibald Bell, based at 8 Aldgate Street.

In the US, Wheatley had to prove her poetic talents to a panel of prominent white men, including the governor of Massachusetts and John Hancock, who would soon sign the Declaration of Independence. While exact details of this “oral examination” are a mystery, whatever Wheatley said worked. They prefaced her poems with an “Attestation”, certifying that “She has been examined by some of the best Judges, and is thought qualified to write them”. Such performative approval was necessary, since readers “would be ready to suspect they were not really the Writings of Phillis [...] an uncultivated barbarian from Africa”.

Wheatley arrived in London with Nathaniel in the summer of 1773, and this “Attestation” prefaced her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, which she published and circulated during a six-week stay. “I was reciev’d in England with such kindness Complaisance, and so many marks of esteem and real Friendship,” she wrote of her meetings with the likes of Benjamin Franklin and the lord mayor of London. An audience was arranged with King George III, whom she had praised for the removal of the Stamp Act, but was cancelled when she was called back to Boston because her mistress Susanna was dying. Wheatley nonetheless had time to visit Westminster Abbey, the British Museum, Sadler’s Wells, Greenwich hospital and the Royal Observatory, and was “show’d the lions, panthers, tigers” in the Tower of London.

“Since my return to America my Master has at the desire of my friends in England given me my freedom,” she wrote in a letter in October 1773. Wheatley had written her way to liberation. She was manumitted three months before Susanna died in 1774. John and Mary would die four years later: the same year Wheatley married a grocer named John Peters, who was formerly enslaved. Records suggest they had three children, all of whom died in infancy. Peters’s debts led to his incarceration and pushed the couple into poverty. Wheatley had prepared a second volume of her poems but, as a scullery maid, could not afford to publish it. It is in these dismal circumstances that the first Black woman to publish a book of any kind died from pneumonia, uncared for and alone, in Boston in December 1784 at the age of 31.

The twists and turns of Wheatley’s life story are so dramatic I’m amazed it hasn’t yet been adapted for TV; in fact, I’m writing a screenplay to rectify that. My research into Black nature poetry – as part of my doctorate and my Radio 3 show Digging for Words – has guided the project, but it is also a personal quest. As a fellow Black female nature poet, approaching 31, childless and living alone, I hope to honour Wheatley’s largely forgotten legacy. Like Wheatley, I was raised in an all-white family, a grain of silt in a sea of white. Our ancestors were colonised on the same continent. We both turned to poetry as a salve for our splintered identities, publishing our first poems as teens about shipwrecks.

Wheatley read John Milton, Alexander Pope, Virgil, Ovid … and ‘as soon as she could read well, she began to make Rhymes’

Wheatley read John Milton, Alexander Pope, Virgil, Ovid … and ‘as soon as she could read well, she began to make Rhymes’

Wheatley shows that a poet might be released from servitude, but not from the shackles of the critical gaze. To be called a “genius” – as she was by Voltaire – is a high compliment, yet Wheatley’s genius is often glimpsed only partially, or under a particular enslaving light. Wheatley reflects on how she, “young in life, by seeming cruel fate / Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat”. In her writing she returns often to her “native shore”: at times it is condemned as a “Pagan land”, at others she questions white exploitation, asking: “Must Ethiopians be employ’d for you?” “How well the Cry for Liberty, and the reverse disposition for the Exercise of oppressive Power over others agree,” her letters note. “I humbly think it does not require the penetration of a philosopher to determine.”

Related articles:

Her poems tune into “Nature’s constant voice”: “birds renew their notes, / And through the air their mingled music floats”, she writes in A Hymn to the Evening. In her descriptive sketches, “feather’d warblers sing across a flow’ry plain”, “dews their gems disclose, / And nectar sparkle on the blooming rose”. Elsewhere, “nature shudders at the furious blast” as “chilling winds return the winter past”. Ships are tossed as “the wind’s fierce tyrant roars”. This turmoil sometimes conveys “the wild tempest of tumultuous grief” – yet the slave ship is ever present too. And she speaks to both slavery and the sublime when her “sons of vegetation rise, / And spread their leafy banners to the skies”.

An Arts Council report revealed that, until 2008, Black and Asian poets represented less than 1% of poets published by mainstream presses in Britain. By 2020 – thanks to the Complete Works mentoring scheme – that figure is thought to have risen to over 20%. But change is only just taking root. A groundbreaking anthology published earlier this year, Nature Matters: Vital Poems from the Global Majority, edited by Mona Arshi and Karen McCarthy Woolf, is the first of its kind in Britain. Where race is often read as a prison, here it is reframed as a prism, magnifying issues of ecological injustice.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The early Wheatley scholar John Shields cursed the “infernal worm” – presumably a bookworm – that “munched and undulated his own avenue” through his copy of Wheatley’s book. Nature gets under the skin of everything. When the Earth is all we have, no critical gatekeeper can fence it off.

Nature Matters is published by Faber & Faber (14.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £13.49. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

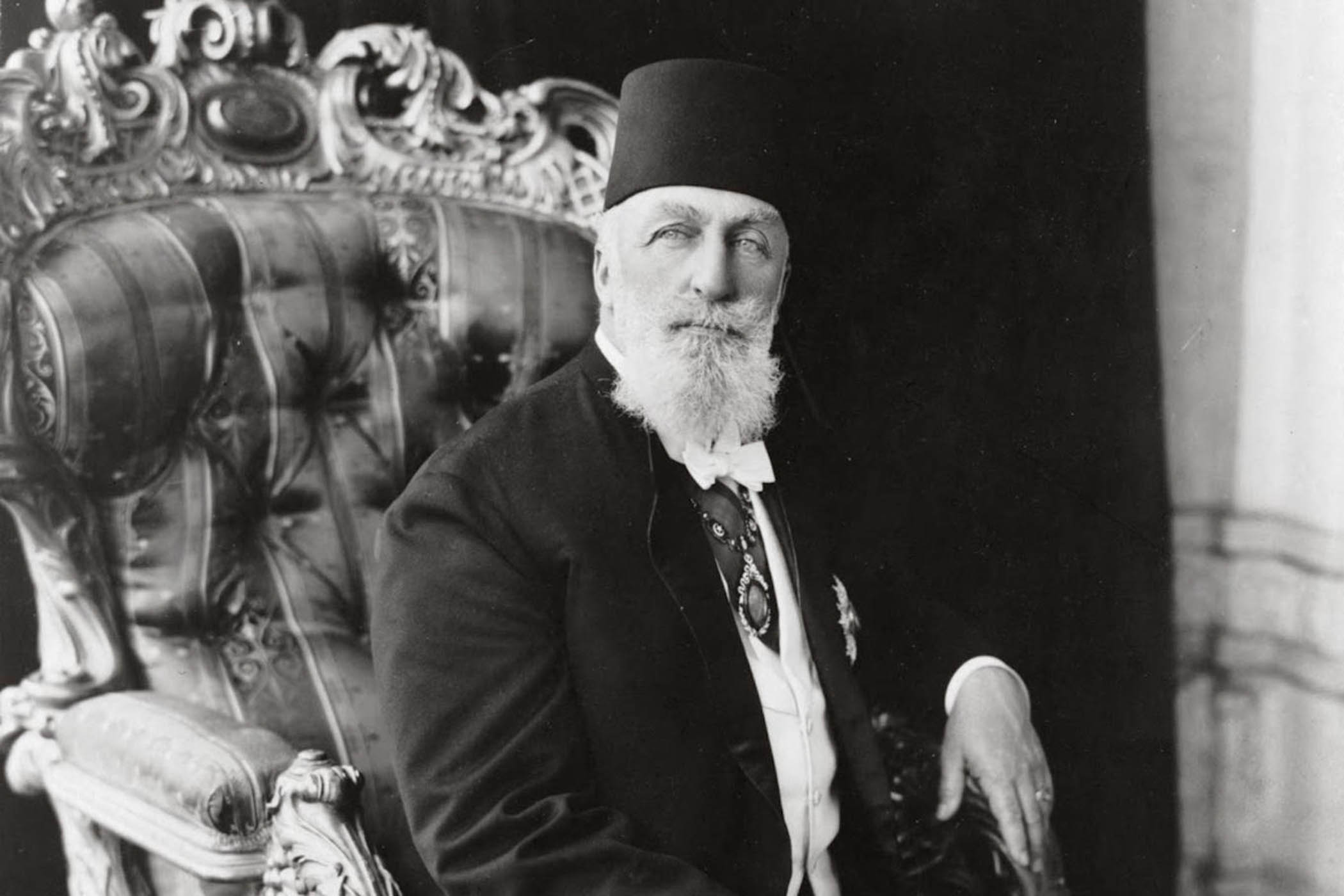

Illustration by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images