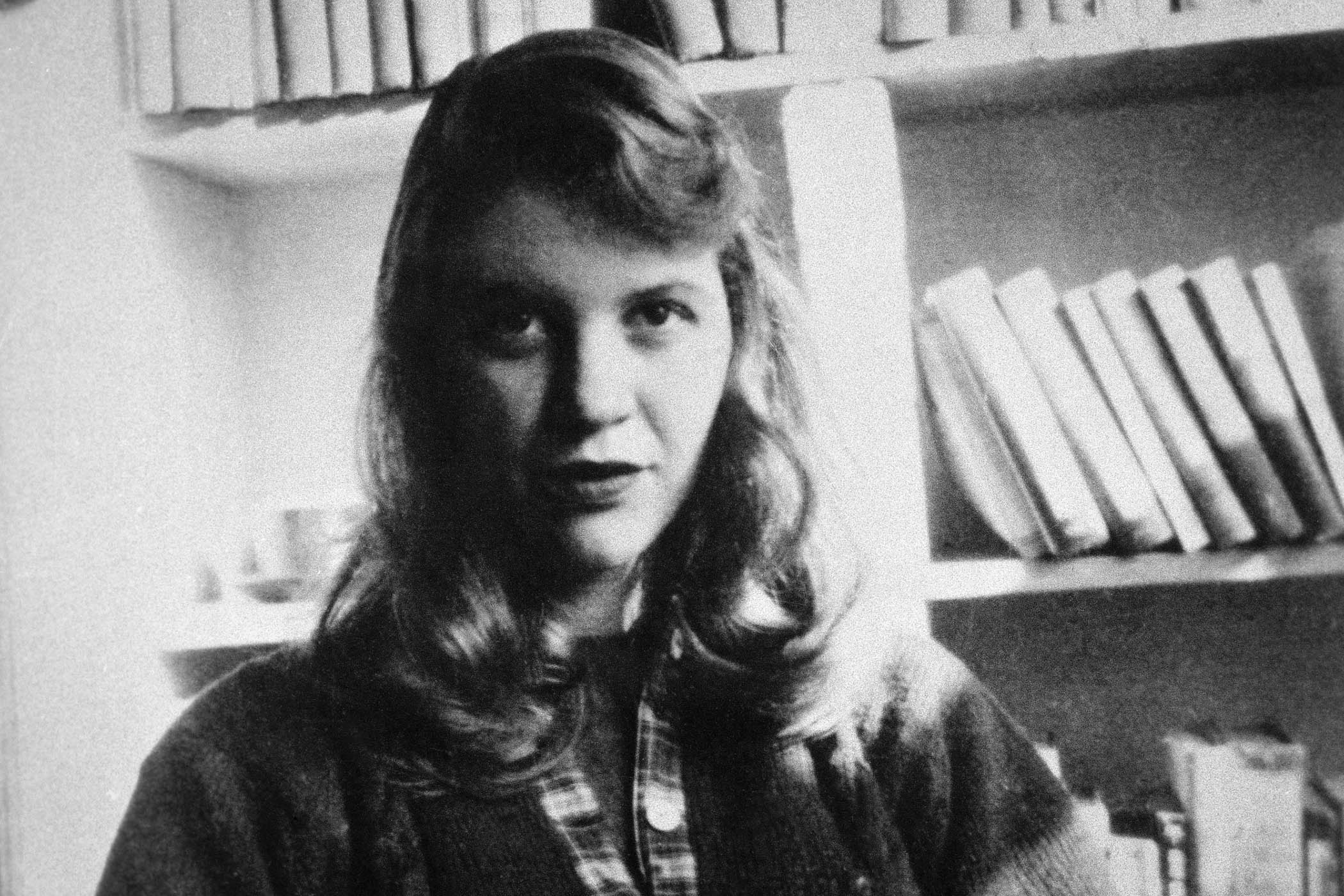

The story of postwar British poetry has been, at least partly, told in the pages of The Observer. Al Alvarez, poetry editor and critic for this paper from 1956 to 1966, was an early champion of Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath, both of whom he befriended. Plath’s first appearance in the paper’s pages came in 1959: tucked unceremoniously into a corner of a book review on 14 June was an untitled poem that would become Night Shift – “Men in white / Undershirts circled, tending / Without stop those greased machines” – in Plath’s first collection the following year (the only collection published in her short lifetime). One issue in August 1962 contained not only a new poem by Plath (Finisterre) but pieces by Hughes (Mountains) and David Wevill, who, along with his wife, Assia Wevill, was tangled up messily in the lives of Plath and Hughes.

In 1961, Alvarez had published a polemic in The Observer titled Beyond the Gentility Principle. “What poetry needs,” he argued, “is a new seriousness.” After the atrocities of the second world war and under the threat of nuclear annihilation, English poets must “drop the pretence” that life “is the same as ever, that gentility, decency and all the other social totems will eventually muddle through”. The essay had a marked influence on young writers such as the émigré Plath, and became the introduction to Alvarez’s taste-making anthology The New Poetry, which proposed the American poets Robert Lowell and John Berryman as lantern-bearers for the rising British generation.

In the cramped column inches of the broadsheet newspaper, poems were part of the inky ecosystem

In the cramped column inches of the broadsheet newspaper, poems were part of the inky ecosystem

Alvarez – whose other lives included poker player, mountaineer, wild swimmer and author of The Savage God, a study of suicide – was succeeded as The Observer’s poetry critic by two poets from The New Poetry stable: first Ian Hamilton and then, in the 1970s, Peter Porter. Others have followed in their footsteps, including Kate Kellaway in the 1990s and more recently Jade Cuttle, a poet and broadcaster with a sideline in historical re-enactment.

Along the way, poets have often moonlighted in the books pages. Seamus Heaney reviewed Philip Larkin’s collected poems (admiring the “solar and lunar illuminations” of his best poems but taking issue with his “punitive haughtiness”) and judged the Observer Arvon poetry prize in 1981, alongside Hughes and Charles Causley (a 29-year-old Andrew Motion was the winner). Stevie Smith wrote on Milton and took issue with an anthology of poetry without men (“awkward, very awkward”).

The Observer's poetry editor Al Alvarez championed talents like Sylvia Plath (main picture)

In the cramped column inches of the broadsheet newspaper, poems were part of the inky ecosystem: in the 1960s you would find them abutting a fiction round-up by Claire Tomalin, or an ad for Nudes of Jean Straker (send a 6d stamp to the “Visual Arts Club” on Soho Square). But as print formats shrank and changed in the digital age, the newspaper poem began to vanish. Starting this week, and aided by the illustrator Chris Riddell, The Observer hopes, in a small way, to reintroduce this rare species back into its natural habitat.

The poet laureate Simon Armitage has his own history with this paper, having interviewed Arctic Monkeys and reviewed a swanky restaurant in Grasmere, among other assignments. But in our first Sunday poem he returns with a piece that acknowledges – as Alvarez would have wanted – our own modern horrors, but finds pleasure where it can, in the spectacle of the fire boat and the language that keeps it afloat. Are we waving or drowning? For poets the answer is invariably both.

Photography courtesy of Getty Images/Penske Media

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Related articles: