Second Life: Having a Child in the Digital Age

Amanda Hess

Abacus, £20, pp272

When I meet women who, like me, gave birth in 2020, I feel an unearned affinity. They also made do without “a village” to ease the strain of early parenthood; they worried about how minute and fresh lungs might fight infection; and they watched online news narrate a global catastrophe while managing a private identity crisis.

But of course, mothers weren’t all in the same boat: some of us were scrolling what was then Twitter on a cruise liner while others were in dinghies, close to capsizing.

In Second Life, Amanda Hess, critic at large for the New York Times’s culture section and pandemic first-time mum, writes with immense skill about the bonding and splintering experiences of pregnancy and parenthood, mediated by the technologies that filter our realities.

Scrolling past discussions about whether parents should reduce their phone use (without doubt), Hess accepts that devices are stitched into our lives, by our sides in sickness, health, boredom, worry, dissociation and joy. The maternal-foetal dyad has become a triad: mama, baby, screen.

Before motherhood, Hess was using the app Flo to track her periods, which distilled her bleeding, moods and hormone fluctuations into a “cool stream of data”, made pretty through the interface’s pink colourway.

After a positive test, “obviously, I told the internet before I told my parents,” Hess writes as she unlocks Flo’s pregnancy mode. This sounds dystopian but is now an established social norm. Two days later, targeted adverts arrive, followed by sponsored content and admission to the “thrumming pregnancy unconscious” of parent message boards.

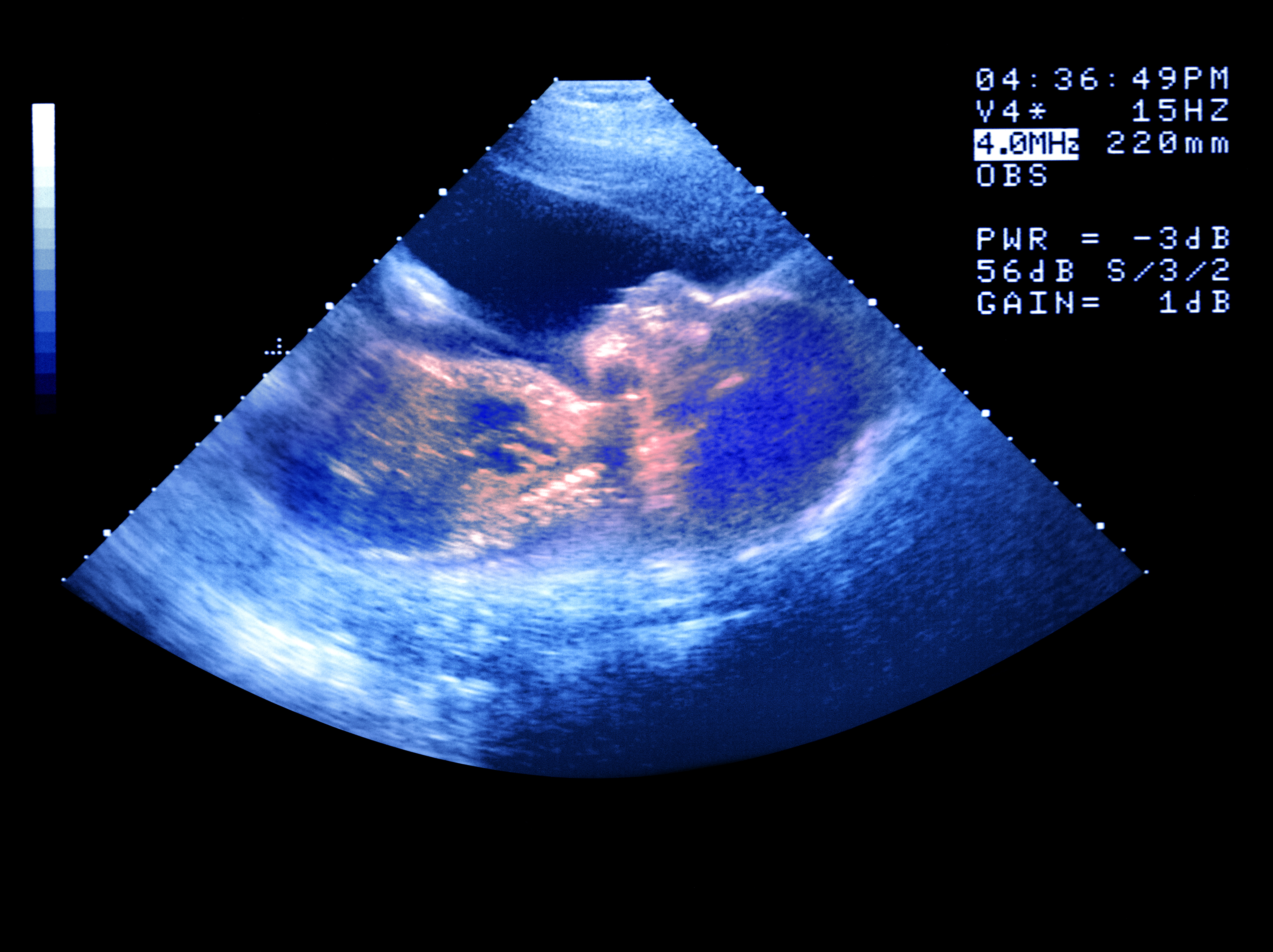

But a routine ultrasound scan at seven months picks up that Hess’s baby has an unusually protruding tongue. Her pregnancy has entered “complication mode”. Only after an MRI scan and rounds of testing does suspicion curdle into a diagnosis: a rare genetic condition called Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. “Don’t Google it,” the doctor warns. As if any millennial could resist.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Pregnant women may feel special, but Hess soon realises she is a foetal vessel and a cash cow (belly oil for $64, anyone?) for entrepreneurs and shameless multilevel marketing.

Algorithms anticipate Hess’s needs, selling her solutions to problems she didn’t know she’d have. In return, she confides her worries in Flo, circumventing the tension and embarrassment that comes with human interaction, and it becomes “accountant of the flesh”, nurse and therapist.

In Covid times, Bessel van der Kolk’s 2014 book on trauma, The Body Keeps the Score, hurtled on to bestseller lists, but as Hess observes, “My phone kept the score,” as a “map of anxieties.”

However, pregnancy platforms assume babies are wanted, white and well. When the prenatal diagnosis is made, Hess sees how the pregnancy industry fetishises normal and fears the alternative: “The internet finally had nothing left to sell me.”

Perinatal technologies, which parse what’s normal, have accompanied us from the start of human reproduction, whether sticks marked with 28 notches to count down our menstrual cycles or the Sims speculum, to lesser-known histories Hess includes with care and fascinating detail in Second Life, such as the first baby monitor from 1938, the 1950s advent of prenatal ultrasound that used “a naval tool for inspecting metal ships”, sex diagnosis and gender reveals, smart breast pumps, pulse oximeter booties, and cribs that shush, rock and watch over the little one so parents don’t have to.

These devices promise to be portals of intimate knowledge, but they risk interfering with parental intuition and medical advice. They also tell fibs, spiking a mother’s cortisol with false positives and misinformation while being careless with our personal data. At medical school, we were taught not to introduce a device or perform a test if we didn’t plan to act upon the result: that rule of thumb is entirely abandoned when the chronic and incurable condition being managed is parental worry.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Joan Didion famously said, a storytelling impulse that is thrown into hyperdrive during pregnancy. Hess turns to the internet to make sense of her son’s condition, a congenital overgrowth syndrome, and wonders if this is a plot twist for which she is to blame. Believing things happen for a reason is appealing, even if that casts mummy as villain.

A single lorazepam tablet taken in early pregnancy (which a nurse unforgivably asks Hess 20 seconds after her son is born and whisked away to the neonatal intensive care unit)? One – or was it two – glasses of wine on her husband’s birthday? A hot bath? Or could it be her “geriatric” status, obstetrically speaking, at 35 years old?

Hess reflects on teratogens – things that can disturb the development of a feotus – and exposures as modern iterations of the Renaissance theory of “maternal impressions”, which stated that a woman’s mindset, morals or even her physical surroundings could mark her baby and produce a “monster”. She shows the lineage of our appetite for control that holds us captive to myths about parental agency over imperfection. Donald Winnicott’s “good enough” mother is dead; the internet tells us that mothers can never be too good, never too vigilant.

Hess also explores how stories take us down roads not taken, a “second life” where we can cosplay other characters and then what we choose to share of them with others online.

While she has a medicalised birth, a C-section and epidural (“it was amazing”), she becomes fascinated by the “epic” tale of freebirth – delivery at home, unassisted by a midwife or even a doula – for women who spurn the hospital model, along with a cluster of other beliefs and technologies, including vaccines and formula feeding, wanting instead to “deprogram” their minds and hark back to a “fantasy of primitive painlessness”.

Hess does not demonise these yearnings – in fact, she somewhat sympathises with them – and criticises medical overconfidence and the health system’s interventionalist mindset. She feels the draw of earthy tradwife life – even in its isolation – as well as the appeal of reclaiming a lost community. But as Hess’s online alter ego goes farther down the rabbit hole, she sees that, below the organic clothes and the homemade meals, lie eugenic ideas, individualism and bigotry.

Aside from Second Life’s relatability and humour, Hess creates community through her brilliance with language. I sighed with recognition about the “hard rind” of a pregnant belly, not cute but “like a brutalist concrete slab”, which becomes a “deflated basketball” when spiked with an amniocentesis needle and then a “punctured waterbed” after a membrane sweep that hurtles her into labour. In beautiful but never airbrushed prose, she tells us she feels “like a slug” rather than a nymph and shares her routine for “extracting the backlog of hardened shit from my ass” as her third trimester colon grinds to a halt.

Hess has pulled off a book that’s acutely empathetic, thoroughly researched, funny, irreverent and moving. I wanted to spend much more time in the company of her thoughts, similar to how I felt on finishing Sheila Heti’s Motherhood, which also admirably carves out space for ambivalence and uncertainty in first-person confessional writing.

Second Life is the best account of the perinatal period since Anne Lamott’s Operating Instructions (1993), sounding out the tender and weird ways in which we create our own user’s manual for parenthood.

Kate Womersley is an NHS doctor in psychiatry who writes about medicine, gender and women’s mental and physical health. Order Second Life at observershop.co.uk to receive a special 20% launch offer. Delivery charges may apply

Photographs by Peter Dazeley/Getty, Loreto Caceres