A prestigious art gallery in New York commissioned a mural on the theme of American life. But when curators saw the designs of the artists who were pitching for the job, the sketches slipped from their nerveless fingers. The drafts depicted the great men of the hour, deep-pocketed patrons of the arts, as “gangster types, dependent on troops, cops and hired thugs to protect their loot”, says author Andy Friend.

In case you’re wondering, this was not a news story that somehow escaped your attention, in which oligarchs and tech titans coughed up for art only to have their largesse thrown back in their faces. No, this shocking case of ingratitude occurred in 1932 at the Museum of Modern Art, and the slighted millionaires included John D Rockefeller, Andrew Mellon and (the original) JP Morgan.

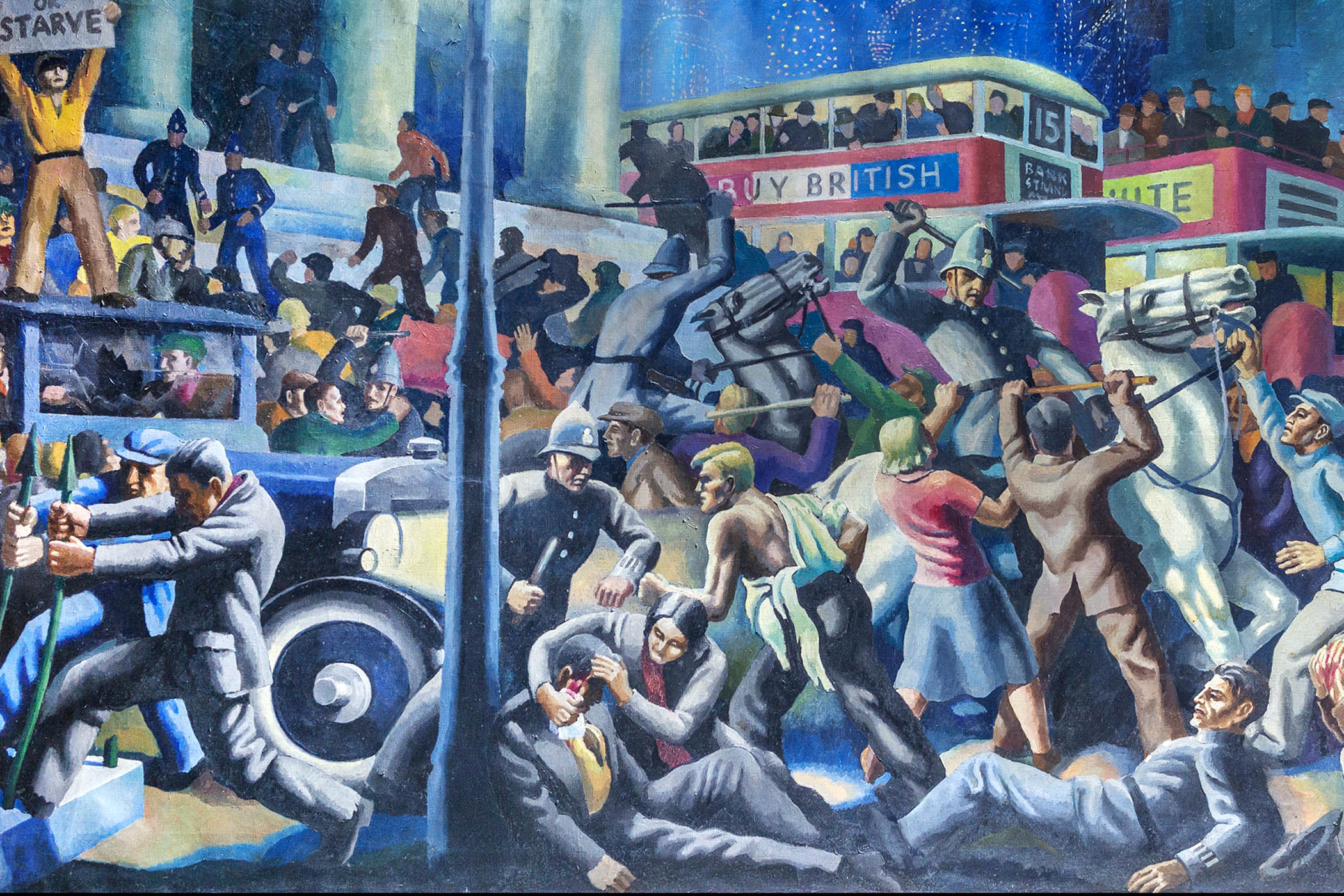

It’s difficult to imagine today’s art crowd biting the manicured pinkies of the men and women who feed them. As Friend writes, ours is a “cultural era where art is an asset class” and it only makes headlines when a work achieves a sky-high price or is exposed as a worthless fake. So it’s refreshing to encounter an art scene that got by without being bankrolled by the 1%, and which engaged with the real world. These were the men and women of the Artists’ International (AI), later the Artists International Association. They came together in the 1930s in response to the threat of fascism and out of a conviction that art wasn’t just for salons, but for street corners too.

The prime movers in Britain were not well known but underemployed artists and designers including Misha Black, Cliff Rowe and the remarkable Pearl Binder, daughter of a Jewish tailor from Manchester, who pioneered children’s television in the UK and travelled widely in the recently formed Soviet Union. In James Boswell and James Fitton, the AI had two blackly comic caricaturists. The group’s meetings and exhibitions drew most of the big names in British art, including Henry Moore, Paul Nash, Vanessa Bell and Laura Knight, and their story takes in figures such as Aldous Huxley, Anthony Blunt, George Orwell and WH Auden. As America emerged from the Great Depression, a similar movement emerged there too: the artists who thumbed their noses at Rockefeller and co.

In its early days, the AI was a little starry-eyed about the USSR, resulting in members being followed by MI5. They were exhorted to make art of a “revolutionary and proletarian” nature, showing “strikes, elections, demonstrations, meetings etc, showing definite working-class activity”.

That sounds like the creative vision of Private Eye’s Dave Spart. But judging by most of the works reproduced in Friend’s book, the message didn’t drown out the art. One remarkable discovery – for me, at least – is Rowe’s The Fried Fish Shop (1936). This painting of the chippy beneath the artist’s bedsit is a slyly mocking riposte to the socialist realist art favoured by Stalin. Wrapping up a fish supper at the counter is Harry Pollitt (whose name sounds a bit like pollock), then the head of the Communist party of Great Britain, while in the crowded dining room, one man sits alone at a table in an ominous shadow: “Uncle Joe” himself.

It’s difficult to imagine today’s art crowd biting the manicured pinkies of those that feed them

It’s difficult to imagine today’s art crowd biting the manicured pinkies of those that feed them

Comrades in Art tells a largely unknown story. Friend, who has written acclaimed studies of the painters Ravilious and John Nash, has done an exemplary job, spending more time among the minutes of long forgotten meetings than is entirely healthy. He quotes a file from Russian intelligence in which the arch spy, Blunt, then the Spectator’s art critic, refers to himself as an “art for art’s sake type with no interest in politics”. Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, snoops on plans for the Soviet pavilion at the 1937 Paris Expo, and then commissions a swastika-clutching eagle, poised as if to swoop down on the figures of heroic Russian workers on the adjacent stand. When Picasso shows Moore his then work in progress, Guernica, made after the levelling of that town in the Spanish civil war, the Spaniard decides that there’s something missing from the figure of a woman running out of a cubicle in the right of frame. Moore looks on nonplussed as the master furnishes a wad of tissue paper to put in her hand.

Disillusion set in among the members of Artists’ International after Stalin signed a non-aggression pact with Hitler. War brought an end to the group’s activities, though they exerted an influence on later generations of talent. Today the group is being celebrated in an ongoing exhibition at Tate Britain, and their ethos can be found in groups of artists like those protesting the conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza. Art, like war, is politics by other means.

Related articles:

Comrades in Art: Artists Against Fascism 1933-1943 by Andy Friend is published by Thames & Hudson (£40). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £36. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Illustration of The Struggle Between the Unemployed and the Police Forces by Cliff Rowe (1932-33) courtesy of Anna Sandra Thornberry