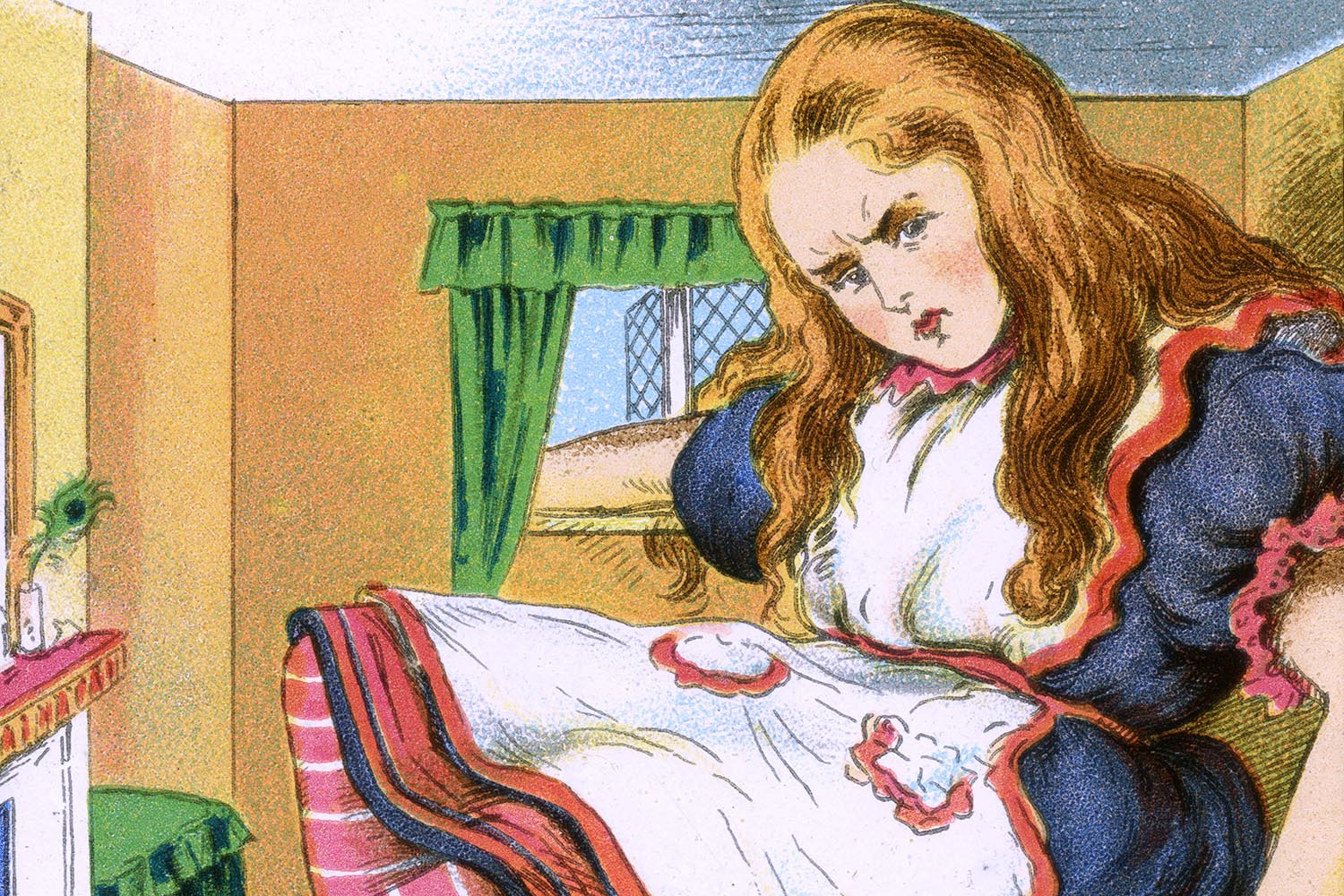

Medicine and stories are intimately related. Patients have life stories. Doctors tell stories to themselves (to maintain their authority) and they offer patients explanatory narratives to boost confidence in their treatments. Stories even inspire diagnoses. Alice-in-Wonderland syndrome is a designation that was first used to describe six patients who experienced a range of perceptual anomalies, including feelings of bodily expansion (just like Lewis Carroll’s Alice). When consciousness becomes chaotic, people confabulate; they invent stories to create a comforting illusion of coherence.

Pria Anand is an American neurologist and in this, her first book, she presents the stories of her patients along with her own (mostly as a doctor and mother) to explore what happens when brains go wrong. For Anand, every diagnosis “hinges on a story” and neurological symptoms are “metonymic for the human condition”. She confesses her shortcomings as a practitioner with refreshing honesty and is equally candid about what happens when she becomes a “patient” herself.

After the birth of her second child, for example, she “leaks milk” and “clots of dark, congealed blood” fall out of her. She argues, plausibly, that her sensitivity to narrative has made her a much better doctor. She is alert to the body’s “tells” and the concentric shells of narrative in which neurological problems manifest themselves.

Anand reminds us that “words have power” and stresses how fundamental language is to being human. In one study, pregnant women were asked to read aloud The Cat in the Hat twice a day. Could babies in the womb learn to recognise phonemes and the “contours” of a story? In the hours and days after they were born, they were presented with a recording of the story and another they’d not heard in utero, and they “overwhelmingly chose to hear the story they knew over the unfamiliar one” (where sucking was used as a measure of interest). Receptivity to language is deeply wired into the brain.

Anand’s own expressive gifts are particularly powerful when she is writing about pain. Some children are born with insensitivity to pain and consequently chew their tongues and fingers. One 10-year-old with the condition became a street performer and entertained the public by pushing knives through his arms. He died at the age of 13 after jumping off a roof.

In another case, a man – originally a marine corps clarinettist – became a vaudeville artist known as the human pin cushion. Some 50 or 60 “pins” would be pushed into his body during every show. He agreed to be crucified with gold-plated metal spikes, but this dubious spectacle was prematurely abandoned when a woman in the audience fainted.

Our purchase on existence is much less secure than we commonly acknowledge

Our purchase on existence is much less secure than we commonly acknowledge

Congenital pain insensitivity has a truly horrific opposite: paroxysmal extreme pain disorder. Severe pain is triggered in body parts such as the eyes or rectum by things as seemingly harmless as a cold wind or eating. Attacks usually begin in infancy and foetal heart-rate recordings from one baby girl suggested she may have started suffering in the womb. It’s the kind of fact that makes faith in a divine plan laughable.

Neurological memoirs with clinical examples often risk accusations of sensationalism or voyeurism. However, Anand never sacrifices dignity for effect. Despite her disturbing “exhibits”, she is primarily interested in human stories and the sheer perversity of the human condition.

Anand describes her workplace, the Boston Medical Center, as a “safety-net” hospital – one that provides care for people who can’t get treated elsewhere because they lack medical insurance, for example. One of her patients experienced epileptic seizures that involved hearing four chords of a Van Halen song (accompanied by a sense of doom) that repeated like a broken record. Some seizures take the form of spasms of mirthless, uncontrollable laughter: ironically, one of these cases won a happy baby contest. Another patient, with encephalitis, claimed to be already dead. And another presented with symptoms that manifested like a glitch in The Matrix. She saw her son’s red T-shirt shimmer momentarily, turn green, and then revert to being red. It transpired that she was suffering from a neurodegenerative condition, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

The Mind Electric transcends the limitations of the popular science genre and raises broader philosophical questions concerning what it means to be human. Consciousness is embodied, and when brains go wrong it isn’t only our perceptions or memories or communication skills that can be affected, but our relationship with reality – and our sense of who we are. As such, Anand’s stories accumulate and persuade us, almost subliminally, that our purchase on existence is much less secure than we commonly acknowledge. A tiny rupture, an infection, a bang on the head, and everything could be different or disappear. We need to be reminded occasionally that life is precious and horribly contingent.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Neurology can serve that purpose. There are many ways in which human beings come to terms with their fragility. Anand makes a strong case for compassion as a first response; but always informed and fortified with rigorous science.

The Mind Electric by Pria Anand is published by Virago (£22). Order your copy from observershop.co.uk. Delivery charges may apply

Illustration courtesy of Alamy