The Big Hop tells the story of the first nonstop crossing of the Atlantic by plane, a feat achieved on 15 June 1919. It’s The Right Stuff in flat caps, in that it presents a cohort of heroic aviators, two of whom finally perform the “hop”, from Newfoundland to Galway. The pair are not particularly famous (unlike Charles Lindbergh, who made the first solo crossing), and David Rooney does not divulge their identities early on, thereby investing his tale with the accumulating tension of a whodunnit.

The story’s principals are seven young men – three pilots and four navigators – who jostled for the crown, flying three planes manufactured by three British firms. Glory aside, the prize was £10,000 (closer to £1m in today’s money), put up by Alfred Harmsworth, proprietor of the Daily Mail, who tended to wear his own flat cap with a full-length fur coat. For Harmsworth, the development of aviation (the Wright brothers’ momentous lift-off had come in 1903) meant the Channel was no longer a “safety moat” against predatory Germany. In response, Britain must become “air-minded”, hence Harmsworth’s cash prizes for aviation feats, culminating in the Atlantic prize.

The flying school at Brooklands in Surrey was the forcing house for most of the players here. It was a “world apart… where the gentry mixed with the proletariat” (Rooney’s seven being nearer the latter than the former). Crashes were “a necessary part of the deal”: an accident showed where you were going wrong and what needed to be refined. But Brooklands was also like a wild, airborne youth club, where everyone was addicted to the exhilaration of getting “high”. Races and competitions were held: first to take off, last to land. An exasperated message from a local to a pilot – who was showing off just over people’s heads – was painted on a barn door, lain flat: “Fly higher.”

In the first world war, the enemy’s bullets added to the danger of being aloft in the “ethereal” biplanes of the time. Some of the book’s main characters acquired mental scars, brought to light by Rooney’s deep research, though not discussed by the “victims” themselves as they might be today. In October 1915, Ted Brown – born in Glasgow, the son of a US engineer – was 8,000ft above the Battle of Loos when the plane he was navigating was shelled. As it plunged vertically, he had to climb to its rear, since his cockpit was on fire. Weeks later, he crashed again with a worse aftermath. He was captured (with a festering bullet wound) and imprisoned in Germany for 14 months, including a stint in the rat-infested Clausthal camp, high in the Harz mountains. When Brown qualified as a pilot in 1918, his “youthful vitality” had departed. “His eyes stared into the distance as if recalling some memory better left forgotten.” There is a photograph to prove it.

The war forced the pace of aircraft development but the era of commercial flights had barely begun when, in the spring of 1919, the men began testing their planes in the blustery fields of Newfoundland. The “hop” attempts were uncoordinated. A plane would take off while the other airmen watched and waited, genuinely wishing their comrades the best of luck.

One plane went missing over the sea, and we observe the drama through the eyes of the pilot’s wife as she waits by the phone, assailed by false reports and hoaxes. (Someone composed a message in a bottle purporting to be from her husband.) Readers who don’t know the outcome will find the tension near-unbearable.

Rooney’s previous book was also nonfiction (About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks), but The Big Hop reminded me of a John Buchan novel. Rooney has Buchan’s knack for acute imagery (the Atlantic is “a grey waste”) and for spare, compelling action scenes. In 1917, one of the seven aviators, Jack Alcock – affable son of a Manchester coachman – was in a dogfight with a German fighter plane called a Blue Bird over the Dardanelles: “He had got close to his prey – just 50 yards. With such a bombardment of gunfire, he scored a hit. Smoke poured from the machine. Alcock couldn’t tell whether it was engine damage or a smokescreen. The Blue Bird dived away.”

There may be some risk of air sickness reading Rooney – but there is no danger of boredom.

The Big Hop: The First Non-stop Flight Across the Atlantic and Into the Future by David Rooney is published by Chatto & Windus (£22)> Order a copy from observershop.co.uk to receive a 10% discount. Delivery charges may apply. To the Sea By Train: The Golden Age of Railway Travel by Andrew Martin is published on 31 July.

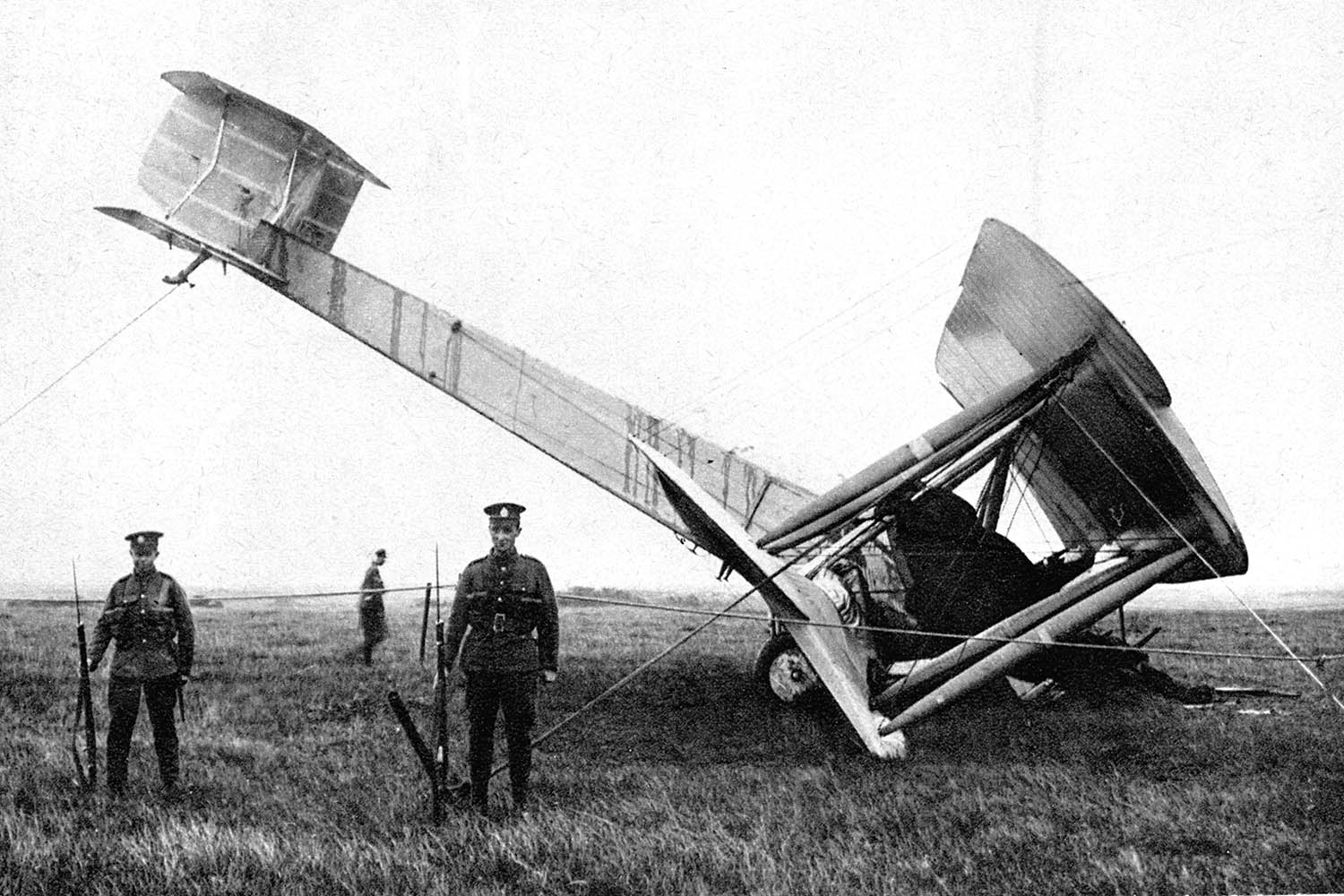

Photograph of the winning plane of the “hop”, after landing in a bog near Clifden in County Galway, Ireland, June 1919. Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy