The Emperor of Gladness

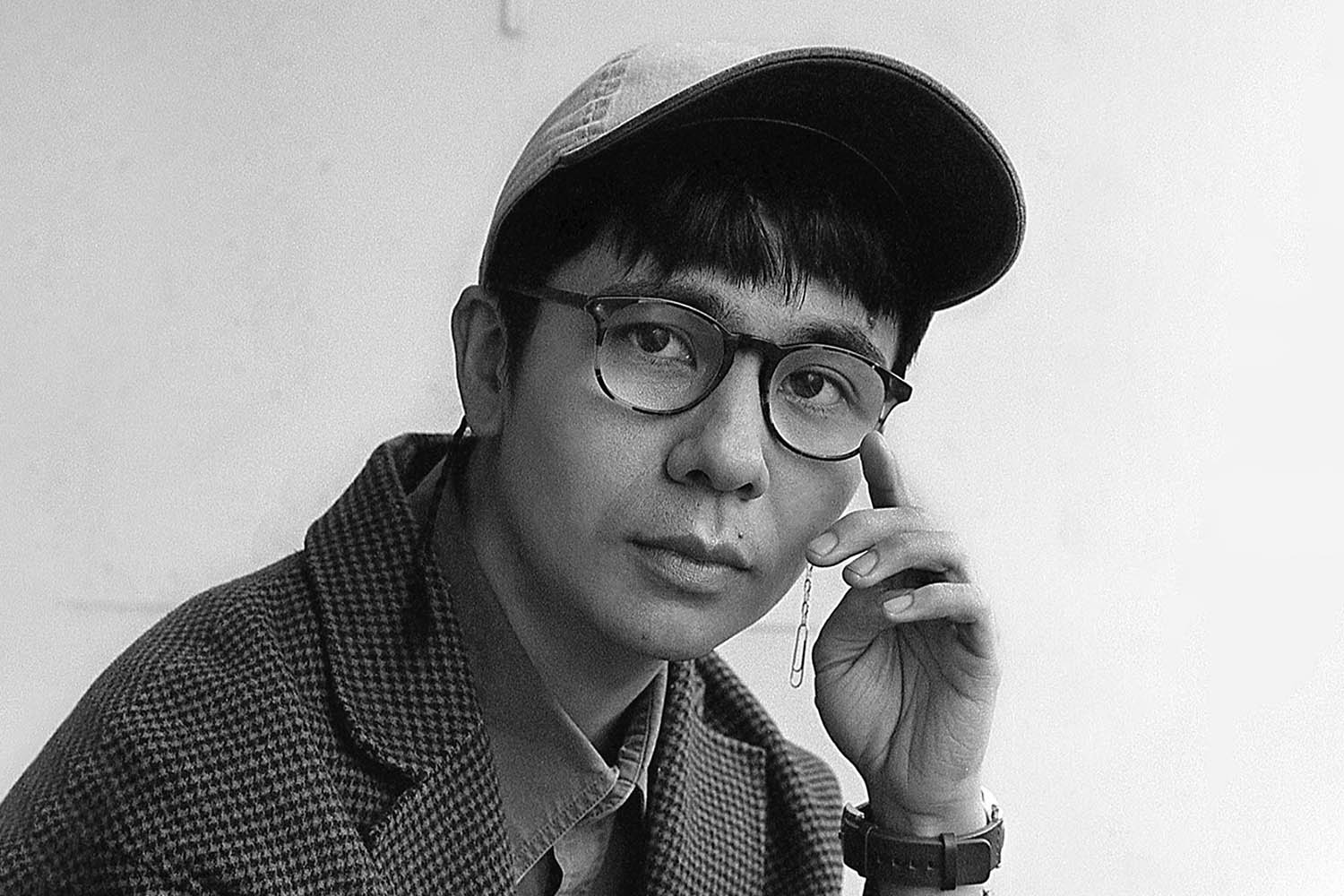

Ocean Vuong

Jonathan Cape, £20, pp416

Ocean Vuong’s first novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, drew on his experience of growing up gay as an opioid-addicted child labourer picking tobacco in small-town Connecticut, where he and his mother arrived as refugees from Vietnam in 1990. He got his break after a move to Brooklyn, studying poetry under the celebrated author Ben Lerner. As the New York Times recently put it: “Vuong seemed destined to stay stuck on society’s margins. Until, that is, he discovered literature and his own enormous gift for writing.”

I doubt Vuong would describe his rise to prize-winning TikTok virality quite that way, not least because his new novel feels designed to torpedo the condescension implicit in such accounts of his astonishing trajectory. Depicting a version of his drug-ravaged post-industrial hometown without portraying his departure as any kind of escape, the book pulls off a tricky balancing act, both gritty and twee, hymning the American culture that formed him while also damning it as lethal.

The protagonist, a Vuong-adjacent shadow-self, is 19-year-old Hai, who, unlike Vuong, quit college in New York before the first semester was over. He’s ready to throw himself off a bridge when he’s spotted by Grazina, an elderly Lithuanian widow who persuades him to live with her as her nurse (leave your disbelief at the door). Their ensuing odd-couple relationship of mutual care is imperilled by the schemes of an estranged son eyeing her property, to say nothing of Hai’s own reluctant conspiracy to steal from Grazina to help his neurodivergent cousin pay his jailed mother’s bail money.

While misery seldom slips from view, we’re regularly blindsided by scenes of humour

While misery seldom slips from view, we’re regularly blindsided by scenes of humour

What follows is a fine-grained social panorama driven by the developing camaraderie of an ensemble cast bonded in precariousness and pain. As well as Hai’s buried grief for a dead lover, there’s in-built tension from his decision to tell his mother he’s studying medicine in Boston, when really he’s still in Connecticut, working in a fast-food franchise, starting his shifts in the bathroom with a pepper grinder and pills.

Significant airtime is given to the triumphs and disasters of Hai’s colleagues, not least BJ, an amateur wrestler from Martinique, and Maureen, a bereaved mother who thinks lizards run the world. Vuong’s scene-making is built around loss and need, but while misery seldom slips from view, we’re regularly blindsided by scenes of humour and tenderness. Despite the abiding hardship, there’s a strangely wistful air to the Obama-era setting, “a time when people still looked up as they walked... your dopamine levels higher for not having been depleted from blue-light screens throughout the day”, as if the Sacklers were merely the warm-up act for the smartphone age.

Viscerally blunt as well as swooningly abstract (death is “a kind of otherhood”), the book is mixed up all the way down. It’s a comfort read stitched together from the horrors of a ghost town rife with murder, suicide and sexual violence; it’s also rooted in everyday mundanity while being constructed around the crashing implausibility of an elderly woman ready to rely for healthcare on a suicidal young man she’s never previously met. Generosity arrives in unexpected guises throughout: in one scene, Hai and his co-workers are terrorised by a tyrannical regional manager, only for us to see later how much he’s hamming up his villainy to ensure the on-site boss isn’t blamed for looming job cuts.

Everyone’s just doing their best, Vuong suggests, his characters spinning whatever yarn it takes to make it through another day. White lies are key to the plot: Hai plays along with Grazina’s delusion that she’s still in Europe, and fields an unexpected call from his mother by saying he’s deep in work at the lab when actually he’s helping a hard-up pal kill pigs (long story). Another thread turns on maintaining the fiction that his long-dead uncle is still alive. And that’s all before you get to the book’s deepest lying invention, when Hai muses on his failed studies in New York, now just a faded dream: “Even now he did not understand the chain of events that led him back to this dirty old town empty-handed.”

Hard not to glimpse Vuong himself between these lines, shaking his head at a real-life path no easier to fathom.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy