I’m with Tchaikovsky. “I like the plot of The Nutcracker not at all,” he wrote. “The ballet is infinitely worse than The Sleeping Beauty.” Yet this two-act confection that began in the worst of circumstances is now a seasonal showstopper.

The problem for Tchaikovsky is that The Nutcracker is the equivalent of the follow-up album. It was commissioned in February 1891 by IA Vsevolozhsky, director of the Imperial Theatres in St Petersburg: he wanted to reunite the composer with the choreographer Marius Petipa in an attempt to replicate the astonishing success of The Sleeping Beauty (1890).

From the beginning everything went wrong. Petipa fell ill shortly before rehearsals were due to begin, leaving its creation to his deputy, Lev Ivanov – a solid choreographer but no genius. But the real issue was the plot – a convoluted tale of enchantment and seven-headed mice. Based on a story by ETA Hoffmann, as adapted by the novelist Alexandre Dumas (père), it featured a child called Marie (now usually called Clara), an inventor called Drosselmeyer and the oddly named Princess Pirlipat, who in a fit of bad temper throws out the hero who has just saved her just because he looks like a nutcracker.

Dumas had softened the harsh edges of the fairytale, producing a narrative that journeys from a children’s party to the magical land of sweets. But it didn’t do much good. The ballet was a flop. “The authors of ballet librettos never weary the intellect of lovers of choreography,” said one critic. “But The Nutcracker has no story at all.”

He was quite right. The Nutcracker is in my opinion quite the weirdest work ever to become a popular success; a fever dream that often disappoints. Its modern ubiquity at Christmas is almost entirely down to George Balanchine, the émigré choreographer who in exile conjured a version for his New York City Ballet full of tradition and colour that evoked his memories of a Russian Christmas.

Now it is everywhere, vital to dance companies not just as a festive celebration but as guaranteed income to subsidise work throughout the year. It’s estimated that in the US, The Nutcracker generates 40% of all annual ballet ticket sales. In the UK, as Paul James, chief executive of the Birmingham Royal Ballet explains: “It is essential as a financial plank. You can guarantee a profit, which on the whole we don’t make.” He adds: “It has that Christmas box element to it that is just unbeatable.”

As someone who has always struggled with The Nutcracker, I almost feel inspired. Then The Observer suggested that I should try to overcome my seasonal scepticism and see as many Nutcrackers as I could find in a week. Because I am an obedient journalist, I set off on my own voyage of discovery. Fortunately, the Scottish Ballet’s Wee Nutcracker and Carlos Acosta’s Nutcracker in Havana opened outside my time frame, or the travel may have broken me. And I just couldn’t make Northern Ballet’s handsome production, which opened on Wednesday, because I do have a life.

Friday

The Nutcracker at the Royal Ballet and Opera

“Oh this is so lovely,” says my friend Rachel as we meet under the tree. “Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without The Nutcracker.” Bah humbug, say I, and stump off to take my seat.

The Royal Ballet’s production was created in 1984 by Peter Wright, who celebrated his 99th birthday on the opening night of this run. Tonight’s is the 539th performance of the show – it must be doing something right. The designs by Julia Trevelyan Oman place the children’s party of the first act in a comfortable Victorian world; the second part set in the Kingdom of Sweets is all pink and gold and sparkle, a jewel box for some fancy dancing.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Wright has done his best to wrestle the different elements into a coherent whole. His Drosselmeyer is a magician, trying to save his nephew from his entrapment inside the body of a nutcracker. The toy is transformed into a handsome prince when Clara saves him from a magical battle between marauding mice and toy soldiers. Her love frees the nephew from the spell (keep up), and they travel together to meet the Sugar Plum Fairy and her cavalier, and then return to reality, restored.

Watching it, I remember the comment about Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot as having a first act where nothing happens and a second act where nothing happens again. The Nutcracker is the balletic equivalent of Godot. But in between those two acts something wonderful does happen: a Christmas tree grows to many times its normal size, and Tchaikovsky’s music soars as pirouetting human snowflakes whirl in the kingdom of ice and snow.

Before the show I speak to Royal Ballet principal Sarah Lamb, who has been dancing in the ballet since she was eight. “This Nutcracker is like a family member,” she says, sagely. “You may not adore them every moment of the day, but you love them and they are part of you.”

She’s right. I cast aside my inner Scrooge and let myself fall under the spell of tonight’s Sugar Plum Fairy, Akane Takada, and her cavalier, Vadim Muntagirov. Luca Acri is an ardent Nutcracker; Yu Hang a lyrical Clara. There’s paper snow, angels and a sleigh. It’s Christmas.

Saturday

Sarah Crompton at the Birmingham Royal Ballet. Main image: at the Royal Ballet’s Nutcracker

Six years after he choreographed the Royal Ballet’s Nutcracker, Peter Wright made a second version for Birmingham Royal Ballet, where he was director. It was better, and he has since incorporated many elements of it into the London company’s production.

The Birmingham Hippodrome is packed with youngsters for the matinee – many are clearly experiencing their first ballet. I always wonder about this as a starting point. It’s true that they can enjoy the conjuring tricks and identify with the children getting up to no good as a Christmas party descends into mayhem. But there’s not much plot to hold their attention.

Thanks to John Macfarlane’s richly colourful designs, however, there is plenty of drama. This Christmas tree really grows, its huge branches pushing outwards. Combined with Tchaikovsky’s music, the effect is thrillingly transformational, and the snowflakes look pretty as a picture, while Clara flies across the stage on the wings of a huge goose.

The girl on the booster seat in front of me looks entranced, and thanks to the heartfelt dancing of Sophie Walters as Clara and Yasiel Hodelin Bello as her attentive Prince, I begin to thaw. Then I get to Birmingham New Street station. All trains to London cancelled. My Christmas spirit subsides.

Sunday

At Let’s All Dance at the Old Court in Windsor

If it’s Sunday, it must be … oh yes, The Nutcracker. First to the tiny Old Court in Windsor where the enterprising Let’s All Dance are presenting a pocket handkerchief-sized version: just seven dancers and a stage so small that Fritz, Clara’s naughty brother, collides with the Christmas tree when he’s playing up. It’s good-hearted and sweet. And real wet snow falls on the audience. Plus plenty of Nutcracker dolls and tiaras for a combined price of £25. But it once again strikes me as odd that today’s children would be seduced by a wooden doll with an ugly face who performs a function that is not a regular feature of 21st-century life.

Then to the Coliseum in London, where English National Ballet’s Nutcracker has been a staple for as long as I can remember, in various incarnations of varying quality. That’s the thing about The Nutcracker – there is so little of the original choreography extant, that everyone can have their own go. This version, by Aaron S Watkin and Arielle Smith, premiered last year and has the inspired idea of making Drosselmeyer run a sweet shop, which gives some sort of through line to the plot, and allows Dick Bird’s designs to run riot. The tree is disappointing, but I like the way Clara kills the evil Mouse King with a sword rather than bashing him over the head with a ballet slipper.

At the English National Ballet, the second Nutcracker of the day

It’s interesting how closely all these Nutcrackers stick to the original plot, giving it a twist rather than a thorough-going workover. Two of my favourite productions are Matthew Bourne’s version (available on BBC iPlayer all through Christmas) – which starts in an orphanage, introduces skaters and turns Sugar into a love rival for Clara – and Mark Morris’s The Hard Nut, a radical rethinking that incorporates a telling of Hoffmann’s story and has the best snowflakes ever. Carlos Acosta’s Nutcracker in Havana, which continues its tour outside the time frame of this feature, changes everything by adding Cuban rhythms to Tchaikovsky.

English National Ballet’s Nutcracker, on the other hand, is perfectly digestible but saccharine. The addition of dancing Liquorice Allsorts in the form of children ups the cuteness quality quite considerably.

Monday

Little Bulb’s production at St Martin’s theatre

Little Bulb’s Nutcracker at St Martin’s theatre, where The Mousetrap plays in the evenings, was advertised all over the underground, so I thought I had better see it. But it’s a kids’ show with a silly story – and its basic lack of interest made me quite cross.

Tuesday

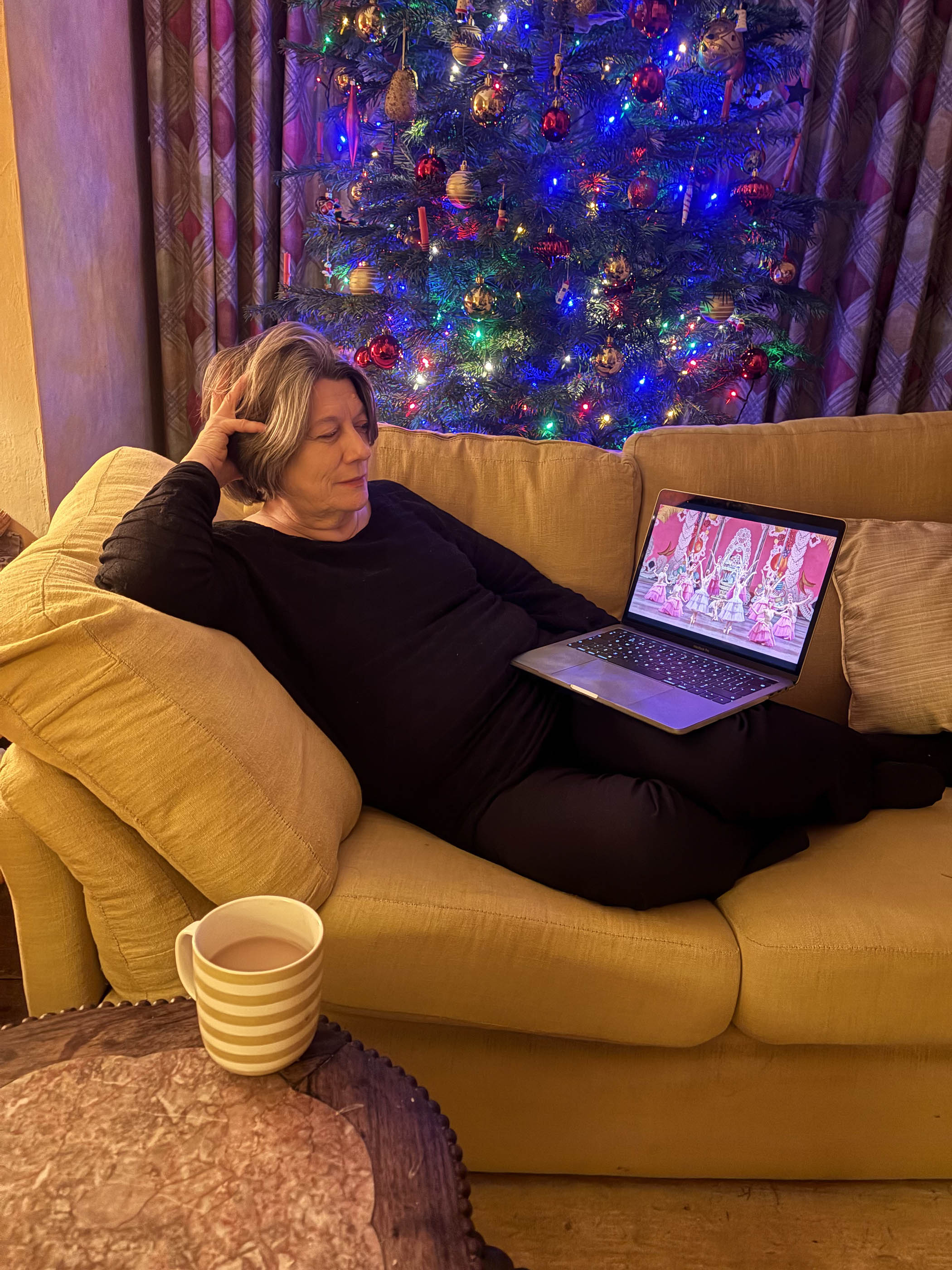

Watching the 1954 George Balanchine version (on Marquee TV)

I have become the person who sings The Nutcracker when I wake up. So I decide to sit on the sofa and watch George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker, created in 1954 and available on Marquee TV. It’s long, full of music now excised from most British productions, and rammed with children playing multiple parts.

This guarantees extensive ticket sales for friends and family, but also allows Balanchine to play with scale, making the tinsel-festooned Christmas tree (pulled up with a hand crank and ropes) tower over the miniature figures fighting and dancing on stage. There are also children as angels.

The whole thing is rather blissful, partly because it’s unfamiliar, but also because Balanchine doesn’t bother too much with making sense of everything, he just lets everyone dance. I am reminded of something Sarah Lamb told me about her dancer husband Patrick Thornberry. One Christmas he was recovering from an operation and so he watched The Nutcracker on TV.

“It wasn’t like he hadn’t seen the magic of ballet before. But he was just so enthusiastic. And it made me stop and think. This is so life-affirming. It makes people happy. It’s not just for children. People need it in their life.” My bah humbug dies in my throat.

Wednesday

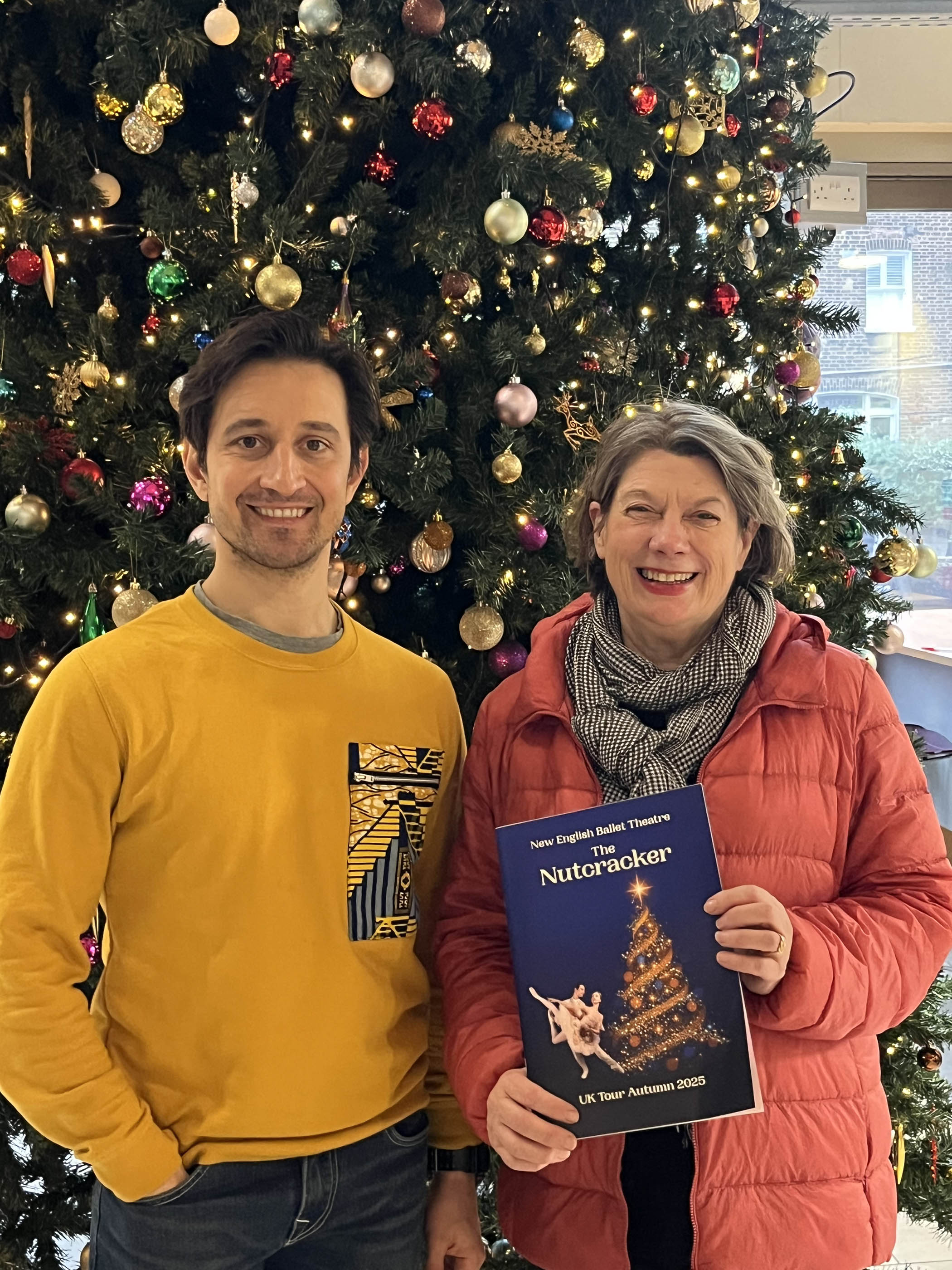

With choreographer Valentino Zucchetti, New English Ballet Theatre

The dancer and choreographer Valentino Zucchetti is having a bad day. His touring version of The Nutcracker for the New English Ballet Theatre has just returned from performances in the Bahamas. But the dancers and 28 suitcases of costumes and tutus got stuck in Miami when their flight was cancelled on the way back, and the rehearsal for their run at the Sainsbury theatre at Lamda in Hammersmith, London, had to be curtailed.

Zucchetti’s first experience of The Nutcracker was as a child at La Scala Milan, dancing in Nureyev’s production, a Freudian Nutcracker where Drosselmeyer became the Prince, taking Clara on a journey of sexual awakening. (I always liked that idea; it responds to something in the music that the Kingdom of Sweets absolutely does not.) Zucchetti has danced most parts in the Royal Ballet’s version and always loved it. “The atmosphere is so nice,” he says. “You can abandon yourself to it.”

His version – which has played to theatres that normally never see ballet, such as Radlett, Sevenoaks and Welwyn Garden City – is compact and contemporary, with Joshie Harriette’s inventive lighting doing a lot of heavy lifting on the magic front. Zucchetti’s choreography is light and cleverly patterned. It’s small but brightly packaged.

As I leave the auditorium, the Sugar Plum Fairy (Liudmila Konovalova) is practising taking a bow, smiling brightly, her tutu gleaming in the light. It’s raining outside. But Tchaikovsky runs through my head and I dance a little through the raindrops.

Main image by Sophia Evans for The Observer. Other photographs by Sarah Crompton/Andrej Uspenski