The sound of the Who’s Quadrophenia rings into the past and out into the future. When the album was released in 1973 it looked back a decade to the heyday of the mods, a tribe distinguished by their clothes and their musical tastes who met to battle their arch-rivals, the rockers, on Brighton beach.

Its arrival on the scene prompted a mod revival, and the 1979 film Quadrophenia directed by Franc Roddam, which introduced a new generation of rising British actors, Phil Daniels, Timothy Spall and the quaintly credited Raymond Winstone among them.

That film, with its devastating central performance from Daniels as Jimmy, the lost and lonely Londoner yearning to belong, to make his mark in a world that seems to hold his aspirations in contempt, became a template for a portrait of disaffected youth. It’s a cry of misunderstanding that echoes down the years, still watched and understood by another generation.

Pete Townshend, Quadrophenia’s composer and key progenitor, has clearly always loved this “rock opera” and its impact. He also happens to like ballet, since the Who’s first manager, Kit Lambert, was the son of composer Constant Lambert, the Royal Ballet’s founding music director, and he used to sneak into the family’s empty box and watch a show. (He also apparently fell down drunk in a lift in front of the prima ballerina Margot Fonteyn, but that is another story.)

When Townshend’s wife, the composer Rachel Fuller, produced an orchestrated score of the music, the scene was set for the arrival of Quadrophenia, a Mod Ballet, a production nurtured with love, care – and a certain commercial acumen. Like Black Sabbath – the Ballet (premiered by Birmingham Royal Ballet in 2023) and even Just for One Day – the Live Aid Musical, it seeks to reach an audience other works do not: the nostalgic rock fan in search of a good time.

A still from the 1979 film, starring Phil Daniels (front, centre right) as Jimmy

The result is strangely subdued. A thoughtful, pulsating album and a raucous, socially aware film have been smoothed down into a polite sequence of fastidiously posed scenes, one following the other in the semblance of a narrative but without any dramatic thrust or energetic intent.

The lush, bombastic orchestration by Fuller and Martin Batchelar, recorded by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, deprives Townshend’s music of bite and energy; the movement never offers anything to compensate. It’s characteristic of the miscalculation of the enterprise that Jimmy’s addiction to amphetamines – the blues that fuel his plunge into depression – is depicted by one rather elegant dancer (Amaris Pearl Gillies) in a blue dress, playing a character called Drugs.

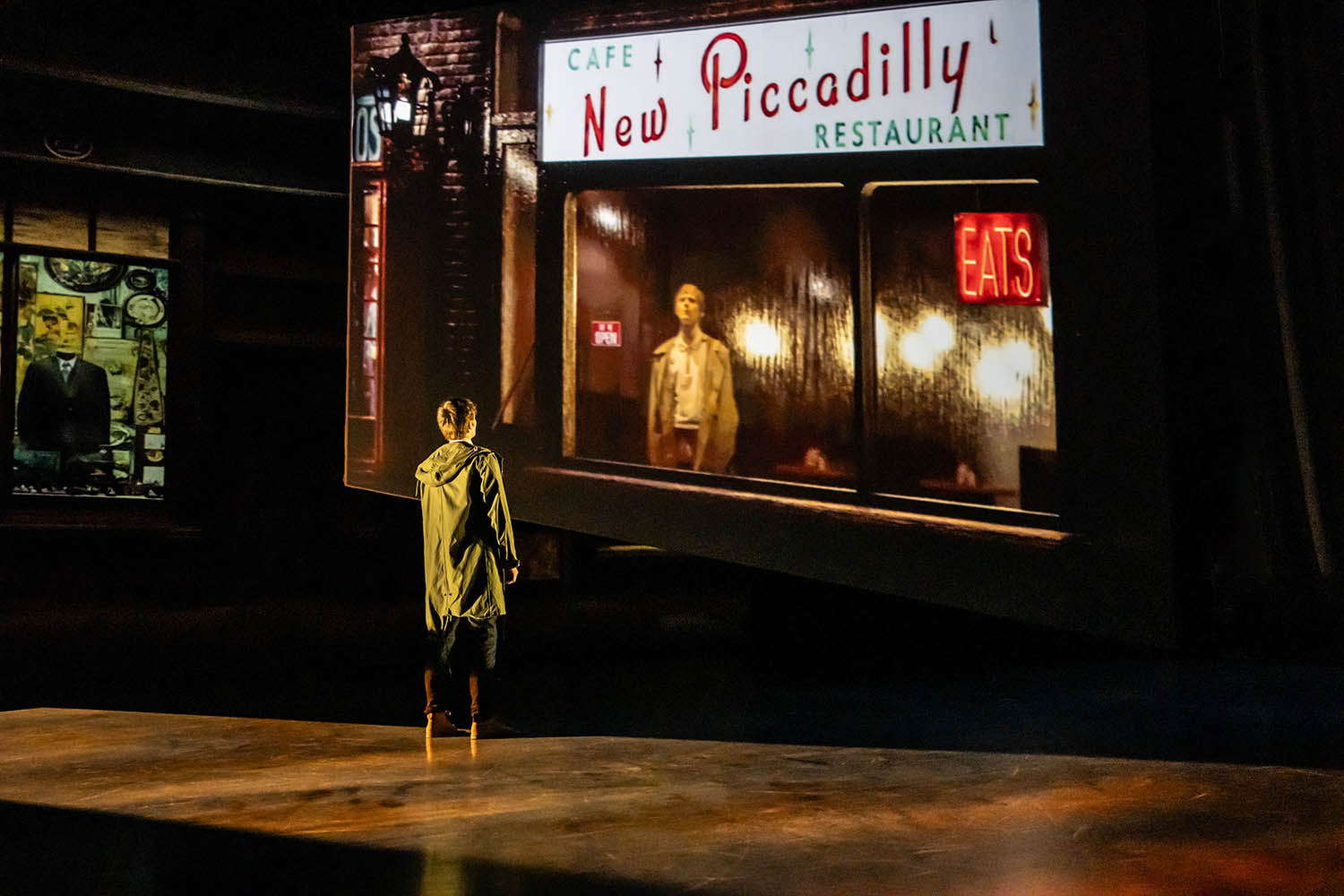

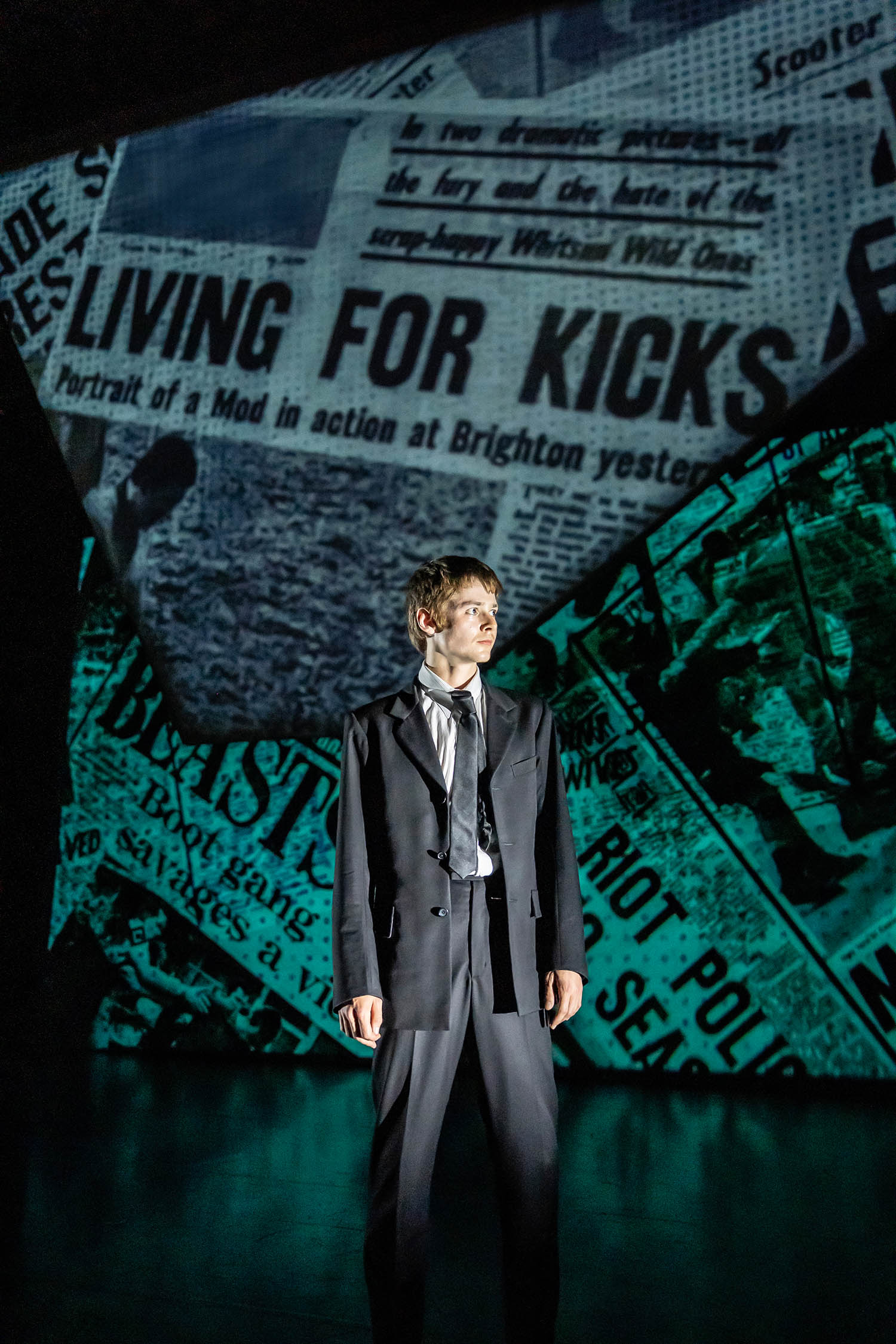

Yet it opens promisingly. Amid a swirling video of a roiling sea, Paris Fitzpatrick’s stick-thin, sharply suited Jimmy stands on a wedge-shaped platform, contemplating his future. Suddenly, four other figures appear: the four conflicting sides of his personality, the quad devised by Townshend to reflect the contrasting personalities of the Who itself. There’s the romantic (Townshend), the tough guy (lead singer Roger Daltrey), the lunatic (Keith Moon) and the hypocrite or cynic (John Entwistle).

The dancers (Seirian Griffiths, Curtis Angus, Dylan Jones and Will Bozier) line up behind Fitzpatrick in different coloured suits, mimicking his movements, their arms unfolding in sequence like a wave. Yet from that point onwards, these alter egos are never properly integrated into the action and, crucially, their presence detracts from the sense of Jimmy’s isolation.

Choreographer Paul Roberts, best known for his work with pop stars such as Harry Styles and the Spice Girls, and director Rob Ashford strive for narrative clarity yet never quite make Jimmy’s story come to life. We see him fall out with his drunken dad (Stuart Neal, excellent), idolise the dynamic Ace Face (an impressive Dan Baines) and pursue a cool girl (Serena McCall, in an incredibly limited role).

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

But each scene follows the next without much momentum, relying on a generic modern choreography of twisting jumps and rolls, fluid falls across the back and raised lifts whether the action is depicting the famous fight between mods and rockers on Brighton beach (a slo-mo disappointment), his father’s scarring wartime experience or Jimmy’s melancholy when his girl rejects him.

Paris Fitzpatrick as Jimmy

The action is vivid at moments. There’s an aching duet for Jimmy’s parents, full of stuttering movement that conjures the gulf between them, bridged when Kate Tydman’s befuddled mother pulls her husband into a sad ballroom hold. The Royal Ballet’s Matthew Ball, guesting at some performances as the rock hero the Godfather, wears a union jack jacket and throws pirouettes and jetés in front of a bank of white lights to My Generation. The train journey to Brighton is a lively tapestry of bobbing heads and weaving bodies. Best of all, a nightclub scene brings together a heaving circle of dancers, shoulders twitching, chins jutting, snapping their elbows in an evocation of the dance moves of the time.

The whole thing looks wonderful. Christopher Oram’s sleek design is animated by videos by YeastCulture that fill the stage with outlines of terraced houses or the flyover where the mods gather. Fabiana Piccioli’s lighting creates oblongs of warm orange amid encroaching darkness or floods a nightclub with harsh blue and white light. Paul Smith’s costumes are sharp and enticing.

The Royal Ballet’s Matthew Ball, who guests at some performances as the rock hero the Godfather

Just as in the film, Jimmy’s disintegration roots the action. But where Daniels was given space to break your heart, Fitzpatrick is constantly surrounded by busyness. He is the most expressive of dancers and those instants where he can simply stretch his limbs into shapes of desolation or sit watching the sea around him carry full weight. Yet he has no trajectory to travel, no journey described.

In the end, Quadrophenia, a Mod Ballet feels like a waste of an awful lot of talent. Its intentions are in the right place, but its execution reveals just how very difficult it is to create compelling narrative dance.

Quadrophenia, a Mod Ballet Sadler’s Wells, London EC1

Photographs Johan Persson, Tristram Kenton