Think of a Wes Anderson film, and you’re as likely to think of a thing – a building, a place, a train, a ship, a contraption, an outfit – as you are a person. The Grand Budapest hotel, Asteroid City, the Darjeeling Express and the RV Belafonte are as much characters, endowed with comparable emotional range, as those played by the movies’ often outstanding actors. Anderson, who has said he might have been an architect if he hadn’t become a film-maker, plans his sets with obsessive care, and fills them with more detail than any viewer, without resorting to pause and rewind, can absorb.

He makes a good subject for the Design Museum’s latest cinematic exhibition, to follow its earlier shows of Stanley Kubrick and Tim Burton. Wes Anderson: The Archives, produced in collaboration with Anderson and La Cinémathèque française in Paris, and co-curated by Lucia Savi, is a treasury of models, drawings, costumes, props, polaroids and video clips, a pharaoh’s toyshop of make-believe vending machines, perfume bottles, weapons and submersibles. Movies are like medieval cathedrals for the range of skills and resources they harness to achieve their ultimate effect, which means the museum has the productive abundance of the dream factories to exploit.

Where the Burton exhibition was the final iteration of a production that had spent many years touring the world, this is a new project first seen in Paris earlier this year, and expanded for its London presentation, after which it will go travelling. It draws on the copious archives that the 56-year-old Anderson has stored in Kent from his personal collections in Paris and New York. Ever since Columbia Pictures disposed of the props, costumes and other material created for his first feature film Bottle Rocket (1996), he has insisted on retaining ownership of such things after every subsequent movie.

‘A work of multistorey pink-on-pink architectural patisserie’: the 1/18th-scale model of the Grand Budapest hotel

So it’s a 700-piece-plus cornucopia of Andersonia, with all its invention and ingenuity, and all its archness and artifice. You get to see the 1/18th-scale model of the facade of the Grand Budapest hotel, a work of multistorey pink-on-pink architectural patisserie used for filming the 2014 movie, as well as Tilda Swinton’s golden Klimtian dress from the same production and the fictional Renaissance masterpiece, Boy with Apple, around which the plot revolves. There’s Bill Murray’s diving suit in The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004), and stop-motion puppets from Fantastic Mr Fox (2009) and Isle of Dogs (2018). You learn about the Texas-born director’s often Europhile inspirations – the music of Françoise Hardy and Benjamin Britten, for example, the diving exploits of Jacques Cousteau, or Jacques Henri Lartigue’s photographs of the good-looking and the well-off.

There is the nostalgia for worlds that never quite were and the flirtations with fantasy and kitsch that are Anderson’s trademarks. The show, like his films, imparts a highly controlled, predominantly male spirit – like that of a train set – in which women are often sweet and quietly wise but rarely protagonists, and helpfully indulgent of male eccentricities and ego. A common figure is that of the puzzled nerd, slightly wounded but often ultimately victorious.

Wes Anderson and his cast of puppets

The exhibition is the stronger for the fact that it doesn’t just evoke the Anderson vibe, but offers glimpses of the mechanics by which films are made. You learn a little of the very different techniques he uses for different movies, including live action and stop-motion animation, working at large and small scales, and on location and in studios.

There are hand-drawn storyboards and their more recent animated equivalents, and the short video clips with which Anderson demonstrates the pose or expression he wants from a character. You see the lengths to which he and his team go in order to get their desired effects. For Moonrise Kingdom (2012), they sought out a 13-year-old artist to do the drawings attributed to young Sam Shakusky in the film, and a left-handed girl whose handwriting would look right for his inamorata, Suzy Bishop. When they found a needlework image in a Rhode Island junk shop, they commissioned three more, showing locations in the film, to hang in the background.

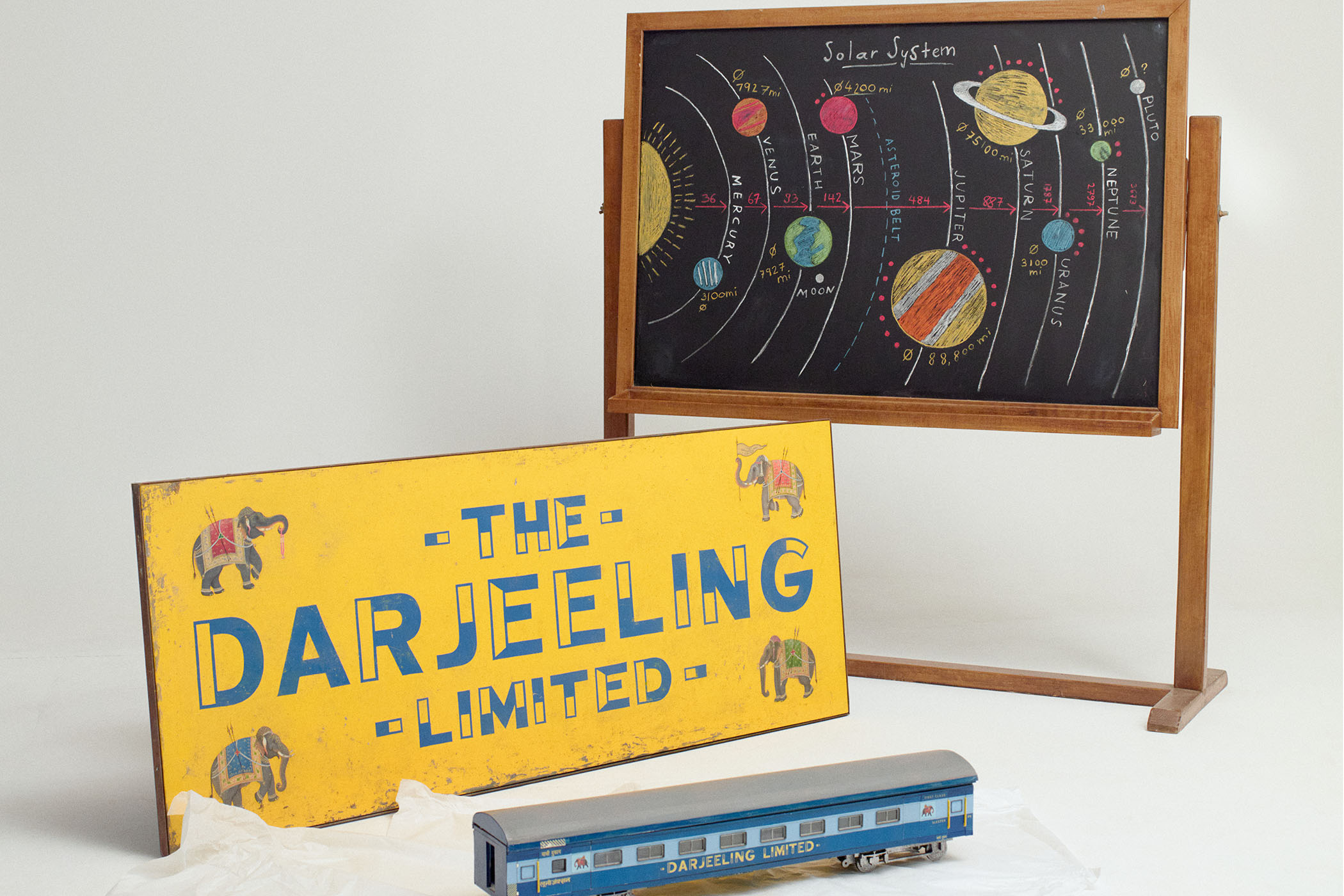

There is a model of two train carriages for The Darjeeling Limited (2007) that both describe their desired look and show how a dolly could fit into the narrow space to achieve the smooth tracking shots Anderson wanted, a combination of form and function that an architect might appreciate. The main characters’ compartment was made in duplicate – one version on each side of the carriage – so that the direction of light would be similar in both the morning and afternoon.

The Tracy Walker puppet from Isle of Dogs

While Anderson’s artistic personality pervades the exhibition, it emphasises the extent to which his films are collective endeavours, made with a team of loyal collaborators who he has gathered over the years. These include the cinematographer Robert Yeoman, the costume designer Milena Canonero, the composer Alexandre Desplat and the director’s brother Eric Chase Anderson, whose contributions include maps and illustrations that help to visualise settings.

It all makes for an absorbing and fascinating experience. The work on show is notably physical, material, handmade and crafted, assisted but not overwhelmed by digital technology. The design of the exhibition installation, by Ab Rogers Design Studio, is confident and uncluttered, despite the multitude of things, giving due space to evoke the spirit of each featured movie and to the details of its making. Rich colours suggest settings and moods, from decadent Mitteleuropa to the south-western American desert. Views through and across help to connect what might be an inchoate sprawl.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Models from The Darjeeling Limited

Your enjoyment may, though, partly depend on your tolerance for the director’s tics and shtick – quite high in my case, as I usually enjoy getting caught up in his ornate universes. But, as The Observer’s film critic Wendy Ide has acutely said, there’s something “punchable” about the “hermetically sealed privilege” of some of Anderson’s work.

You can get weary of the relentless whimsy and wryness, the weightless anguish of the staccato edits and brittle dialogue, and to judge by the patchy reviews of Anderson’s latest, The Phoenician Scheme, there are people who know more about cinema than I do who feel much the same.

To see three decades of supporting material all at once possibly heightens rather than diminishes the suspicion that, for all the sophistication of Anderson’s cultural references, the work is shallower than it first appears. Yet there is still something remarkable here: a distinctive and indefatigable mind able to command large spaces with its output and engage millions, and the Design Museum has done a fine job of showing some of its workings.

Photographs by La Cinémathèque française/20th Century Studios/Charlie Gray/Design Museum