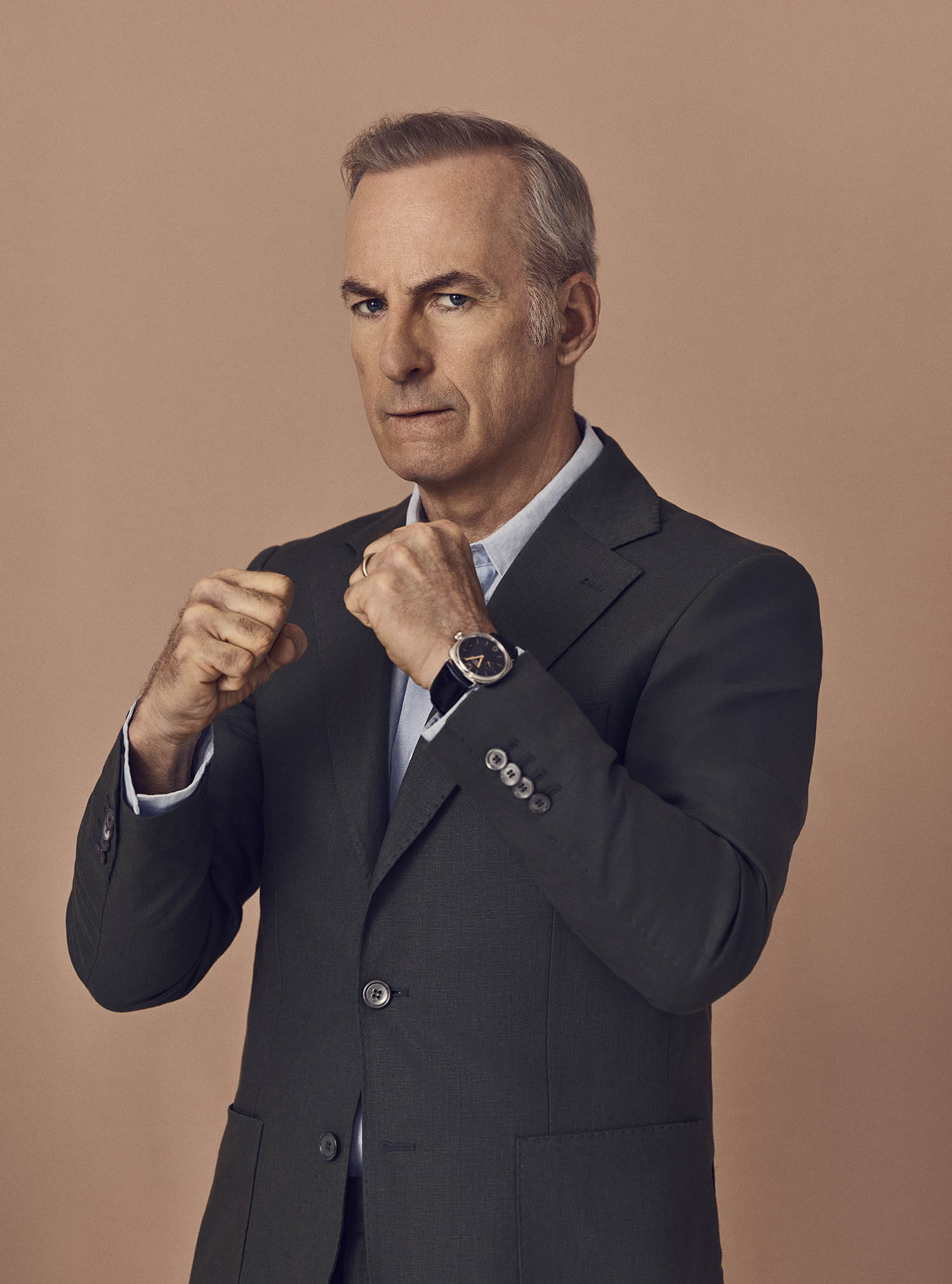

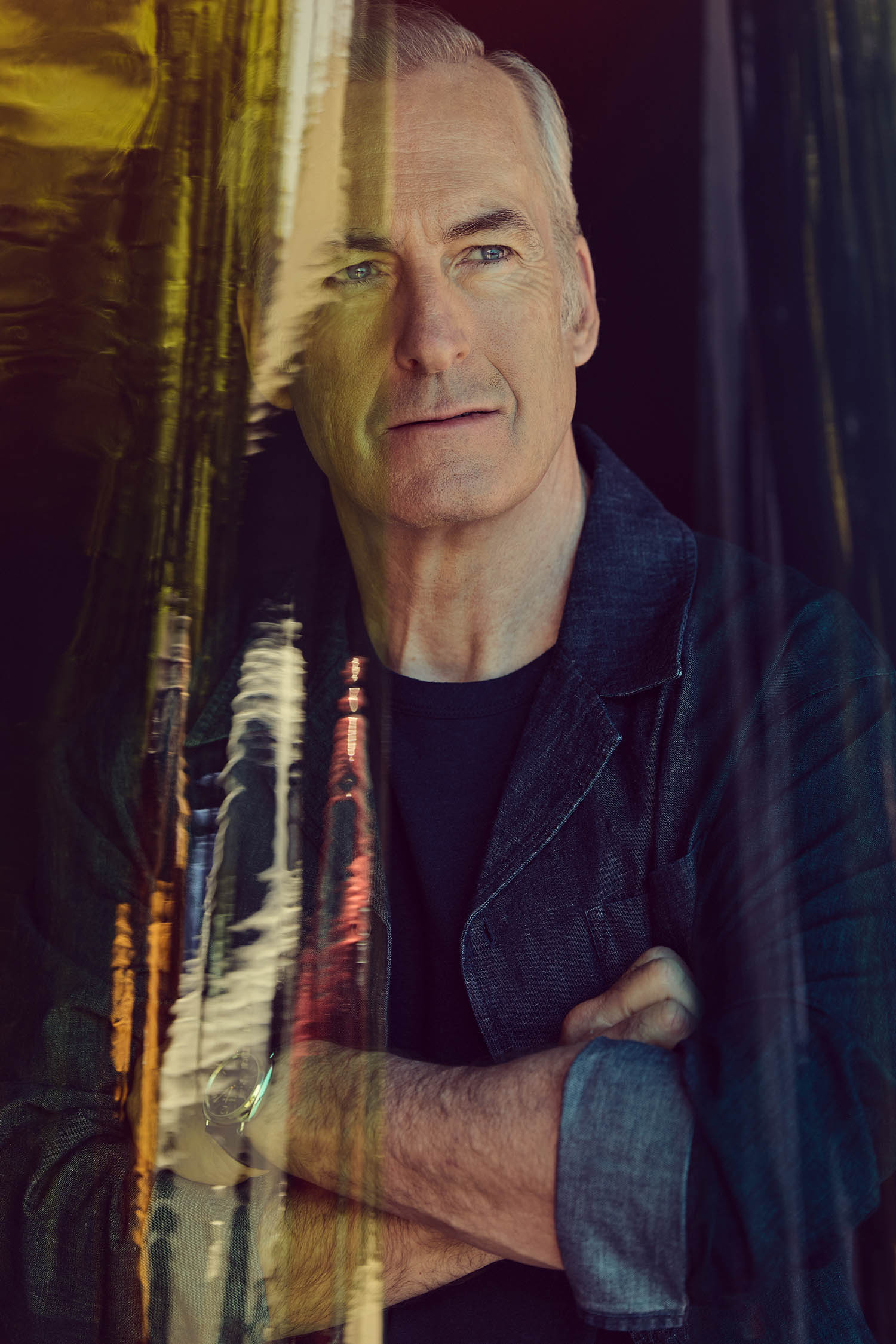

Photographs by Ramona Rosales

Were there even the worst video footage of my interview with Bob Odenkirk – black and white, no sound, one screen in a bank of 12 viewed over the backlit hump of a security guard – you’d know to lean in and watch. Odenkirk is in all modes captivating: when sitting still he looks like an eagle in a baseball cap, vigilant of every glitch in the environment, tilting his head at the rising pitch of a power tool deployed in earshot; when in motion he is a suddenslugger, shadow-boxing to demonstrate ratcheting levels of sloppiness in stage combat, leaping up and twice leaving the room in hot pursuit of something to show me about a subject he really cares about: books or fighting.

We are meeting in the sunny, cluttered office of the Hollywood home, he shares with his wife, Naomi, who is also his manager. When I arrive I almost immediately notice a copy of The Framley Examiner on his coffee table, the elaborately incompetent newspaper from a fictional British town, that induces in me a feeling of panicked, messianic obligation. Since first learning of it I have regularly Googled all four of its writers and their marital statuses. I have ordered at least 10 copies, then sat with their recipients and demanded they read aloud anything that made them laugh.

That Odenkirk not only has a copy of The Framley Examiner here but, I see, has provided its one and only cover blurb, should come as no surprise. His career is an unbroken list of projects and performances that spread by process of fan infliction. Before now, I have never met another American Framley fan in the wild, so in giddy journalistic negligence we begin our time together discussing favourite headlines and sight gags. When he opens a page at random he is immediately giggling.

‘Some part of you has to be like, I’m writing this myself’

‘Some part of you has to be like, I’m writing this myself’

Bob Odenkirk

“I give away so many of these things,” he says. “This is actually my last copy, and I promised to mail it to Jim Downey.” (James Downey: the closest thing there is to an archbishop of Saturday Night Live, where Odenkirk once worked.) He makes a verbal commitment to order another box of Examiners on Amazon – even stands as if to approach his laptop – and then sits back down, overcome with a headline.

I assume this book talk is preamble to our interview and am not recording when Odenkirk digresses to what he’s reading now. I only think to start 20 minutes in when, for the second time, and with the martial focus of a commander soliciting intel from base, he breaks from conversation to find and download another book on his preferred library app, Libby. Odenkirk is a one-man rebuttal to every ponderous article eulogising the male reader. Among the books in his rotation are a work of French investigative journalism, literary fiction both experimental and classic, art criticism, the autobiography of a famous actor and McCarthy-era snitch, comedy and a whole raft of nonfiction with titles like The Stone or the Feather and the word “mindfulness” prominent on the cover.

With regret, I change the subject. “What is your earliest memory?” I ask.

There’s the briefest pause – buffering, presumably – and then he’s back behind his eyes, anecdote loaded.

Related articles:

“How about this,” he begins. “I was playing baseball, little kid, maybe six or seven. And I had this feeling, I wish someone was watching me.”

I ask if he means someone specific: his scoundrel father, perhaps, who was not around much when he was young? (“I was one of seven,” he says later, “so obviously he came home seven times, but not many more times than that.”) Or more the idea of an audience, some vast anonymous crowd of admirers, inverted on the other side of the lens?

“Oh, I wanted the audience,” he says, abruptly bashful.

Odenkirk has made similarly ambivalent claims before. In his memoir, Comedy Comedy Comedy Drama, from 2022, he describes both the ASMR tingle he occasionally felt on stage and his bewilderment at feeling it, as though he found it strange to realise he was so compelling to people watching.

‘Nobody gave me a chance to act out intense rage in a completely invented space’: Bob Odenkirk

I am here to interview him about his new movie, Nobody 2, the latest entry in a filmography that has, over the decades, seen him transition from writer to producer to leading man. His breakout role, playing Saul Goodman in Breaking Bad, led to starring roles in its spinoff Better Call Saul and then the full-blown Hollywood action movie Nobody. But despite nearly 20 years evidence to the contrary, he seems unsure that the audience wants him back.

I wasn’t out there trying to become more famous as an actor, I was writing. I love writing. I love comedy writing

I wasn’t out there trying to become more famous as an actor, I was writing. I love writing. I love comedy writing

Odenkirk began life as a writer. He received, in his formative years, the majority of his compensation and validation for work off-camera. And when he did perform, was more often the mirror than the light. “I wasn’t out there trying to become more famous as an actor,” he says now. “I was writing. I love writing. I love comedy writing. I had the perfect amount of fame, where the only people who knew me were the ones who liked me. They kind of knew my brain, how I see the world, and they liked it.” For a long time, Odenkirk kept busy with the non-tingly work. For decades, he was a singular figure in American comedy, his career begging description in clickbait terms: This One Weird Guy Is The Secret Ingredient Executives Won’t Tell You About. He’s worked on – and often played an operative role in – a preposterous number of now-canonical shows, and moved through comedy scenes like some non-problematic Zelig.

His first brilliant move was to be born in suburban Illinois in the 1960s. His second was to get bored.

“I went to school when I was young for my age,” he says. “And I left a year early, when I was 16. And then I just tried to find colleges that left me lots of room to invent and create on my own.” Though interested in comedy from childhood – “I started recording comedy sketches on a little Panasonic recorder when I was, like, 11” – there were stints in multiple schools before he arrived in Chicago, a city then experiencing a watershed flourishing of alt comedy. Merely embedding himself in that world was an act of prescient taste and determination, two virtues thematic in Odenkirk’s career. The city was infested with young, unhinged, sporadically brilliant comics. Odenkirk was one, and found others, and became a comedy writer, designating direction to something that might otherwise have been misdiagnosed as a more generalised desire to fuck around with his friends. I get the clearest sense of Odenkirk at this age from his description of his son, Nate, now himself a young comedian in Los Angeles: “He wants to make it as a writer. He doesn’t want to do a straight job. He’s happy to live cheaply, because then he gets to avoid having a straight job. And he’s got a confidence in his work that goes so far as to say, hey, leave it the fuck alone.”

After incubation in Chicago (which was and remains the most honourable place for a comedian to incubate, lacking, as it does, money, weather and potential for career growth), his first television job entailed a move to New York, where he wrote for Saturday Night Live in a cohort that included Mike Myers, David Spade, Adam Sandler and Chris Rock. But his time there was short-lived. By 1991, Odenkirk had completed the migratory cycle of the comedy writer from Chicago to New York to Los Angeles, and had only to repeat the process that served so well in other cities: make cool friends, make cool stuff, make other people look funny by giving them your jokes. What the scene lacked in professionalism, it made up for in potential and cross-pollination – within a few years, Odenkirk’s early friend group in Los Angeles would become synonymous with the Gen-X trademarks of trenchant (if exaggerated) nihilism and a facility with cultural retread heretofore unseen. If you saw them on late night, dunking on day jobs and retrograde dating advice from their parents, they were probably friends of Bob’s: Janeane Garofalo, Sarah Silverman, Patton Oswalt, Margaret Cho and an Atlanta standup with unparalleled ability to engage “dumb eyes” and “gormless grin” named David Cross.

‘My son wants to make it as a writer. He doesn’t want to do a straight job’: Bob Odenkirk

Here is Odenkirk’s flaw as a comedian, without which he might never have thought to collaborate with Cross: he’s not great at telegraphing foolishness. He is foolish, and he can write foolish with the best of them, but in the unconsciously typecasting mind of the audience, a man who looks like Odenkirk is meant for roles like “exterminator who curses within earshot of children” or “dentist unwilling to indulge patient who wants every other tooth extracted, so achieving a crenellated effect, like a turret”. In all of comedy, a better straight man was never devised, but should the scene require any clown but a dour one, a foil in the form of David Cross was essential.

Mr Show, the resultant hybrid live-and-recorded sketch show that Odenkirk and Cross began in 1995, was the first big project in which Odenkirk was writing for himself, rather than ventriloquising. “I think you need to have that to make it as a writer,” he says. “As much as you want to learn, as much as you want to take advice, as much as you want to take good suggestions and brainstorm, some part of you has to be like, ‘Fuck you. I’m writing this myself.’ Let it be a piece of shit. It’ll be mine.”

Released from consideration of other people’s taste and voice, Odenkirk and Cross went on a spree of absurdism, resulting in sketches with such titles as “Rapist”, “Audition” and “History of Everest”. Of course, Mr Show was neglected upon release; of course, it was a cult classic, taped and duplicated and watched to the point of disintegration by thousands of comedy fans. The success of its four seasons, albeit in metrics too ephemeral to register at HBO, established Odenkirk and Cross as the mum and dad of alternative sketch comedy.

Bob Odenkirk as Saul Goodman in Better Call Saul

And so Odenkirk found himself with a sidebar in patronage. Over the next two decades, in addition to his standard yearly output, he became a mentor for young comedians in whom he saw some of his own industrious derangement: Jack Black, Tim Heidecker, Eric Wareheim, Eric André, Nathan Fielder. Even if these names aren’t all familiar, you’ve seen comedy downstream of Odenkirk: the awkward shot held two beats too long before blurring, the premise so stupid it could only have begun as a typo. Incompetent graphic design as gag. Formal gags of any kind, really – the sort of wilfully horrible choices accessible only to amateurs and masters. Proto-memes.

All of this is to say that even the most careless hyperbole could not overstate Odenkirk’s impact on American comedy. Butterfly-effecting him out of the timeline would extinguish not only his own career, but the entire (dominant) breed of humour. His instinct to identify and promote new talent is currently expressed in support for his children, of whom he is sweetly, audibly proud.

“Do either remind you of yourself?” I ask.

“My son is doing the comedy thing, so obviously that reminds me of me. And my daughter, she feels this responsibility to take care of people and I always felt like it was my job to make sure everyone was OK.”

He has collaborated with both of his kids: his daughter Erin illustrated his 2023 book Zilot & Other Important Rhymes, a children’s book of funny poems that make obvious the overlap in skills required to please little kids and comedy nerds, and he regularly appears onstage with his son Nate.

As someone whose formative Odenkirk project was Mr Show, first seeing him in a dramatic role (Little Women, maximally jarring in period costume) had the effect of a dream in which my brain had chosen Spider-Man to play my father – not so much a casting error as some wormhole between realities I thought mutually exclusive. But much of his audience – maybe the majority of it – have only known him in serious roles, Saul Goodman on. His appearance in Breaking Bad was impressive enough. That of all the character options it was his storyline that lived on made Better Call Saul’s critical acclaim feel redundant: to have sustained Vince Gilligan’s interest was surely the highest praise available to any actor.

Starring in his new film Nobody 2

Saul Goodman served as a sampler for Odenkirk’s range of talents. As a conman and a lawyer, the character had endless licence to perform within Odenkirk’s larger performance. It is good acting when Odenkirk makes Saul look like a bad actor; he has similar facility navigating Saul’s two main moods, “desperation” and “atavistic scheming”. Odenkirk has been open about his own near-bankruptcy before getting the role, but while describing the pressure of that period he sounds resoundingly unlike Saul. When I ask if to play Goodman he drew from this period of his real life, he stands, eyes paused on something across the room, idly mangling his baseball cap at the memory.

“It wasn’t the money,” he says. “What I hated was that I went from being the most fun, happy dad, to this angry guy that my kids didn’t recognise.” It was playing shambolic sadsack Saul Goodman that restored Bob Odenkirk to himself as the most fun and happy dad.

The career in dramatic roles for which Odenkirk is lately known won’t shock anyone who watched him in Mr Show. His characters make most sense when scheming and failing – building traps or falling through them. He’s still the same straight man, still stoic and committed and radiant with flop sweat. It’s just the surrounding jokes that have dropped away. When we meet, he has just finished a run of Glengarry Glen Ross on Broadway. Odenkirk, as Shelley Levene – played by Jack Lemmon in the 1992 film – is distinguished by the specifically excruciating hardness of the times on which he’s fallen (sick daughter, mounting hospital bills), and is the character with the most at stake. “Every night I had to believe in myself so much that the audience would think, he might really pull it off.” Which meant he had to break his own heart every night of the show. “I mean, if I did it right.”

Nobody 2, I say, must have been pitched as “John Wick starring Bob Odenkirk” and sold before the elevator door opened. Odenkirk trained with renowned stuntman/Platonic Russian Henchman Daniel Bernhardt in order to perform all his own fight scenes.

“The goal was to make a relatable guy and scenario and feelings,” Odenkirk explains, “and then let him go into a James Bond world.”

I’ve heard the movie dismissed as stunt casting, but stunt casting would be David Cross rhythmically pulping a man to death. Odenkirk plays it straight – and well. Hutch Mansell, his titular nobody, begins the franchise a close relative of Saul Goodman and Shelley Levene: demoralisation in human form. By Nobody 2, he has grown where previous characters have stagnated. The antidote to his despair: finding and killing enemies.

Bob Odenkirk in his Saturday Night Live days

That Odenkirk has chosen relentlessly brutal action movies as his third act might be explained away with claims about those same men who don’t read: besides fiction, they’re also supposed to hate the grim menu of identities available within American masculinity and love fighting as a simple, primal alt. Whatever Odenkirk’s relationship with the sublimated death drive, the inspiration for Nobody came from two harrowing experiences of home invasion. “I had feelings of anger and frustration towards these individuals,” he says. “A movie gave me a chance to act out the intense rage in a completely invented space.” It’s an extreme luxury to process your trauma through commission of a Hollywood franchise, I think, and a hard, or at least weird, sell from even an actor without the handicap of Odenkirk’s entire career this far.

And then he stands and, with a force and economy of motion I associate with early footage of steam trains, outlines with punches the few available cubic feet in his home office. He describes his style as “hard, clumsy, almost just oafish,” but to me he seems extremely strong and good at fighting. Were any variety of violence to break out, I would be surreptitiously trying to get over to his side of the room. Even so, his plausibility has limits. His body isn’t lithe, he explains. (“Is that how you use that word?” He tests the alternative. “I’m not lithe? My body isn’t lithe?”) Then he attempts a low side kick to demonstrate how little he hinges. “I mean, I can’t sell a smooth kick.”

Were there any moves he had to be talked out of? I ask.

He looks mischievous.

“The one-inch punch,” he says. In his memoir, he described his favourite mode of sketch writing as something like humour through punchdrunkenness – taking a bad idea and making it worse, ruining it through to the other side of hard-won uncanny perfection. Is the same thing possible in fight choreography? I ask, as a parting question. He spends the next three minutes rapt in re-enactment of a skirmish that could be mapped to a Mr Show sketch. The details are embargoed until Nobody 2 is released, but I can attest it attains that flawlessly calibrated stupidity, accessible only to amateurs and masters.

Nobody 2 is released in cinemas on 15 August

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy